Jun 27 2019

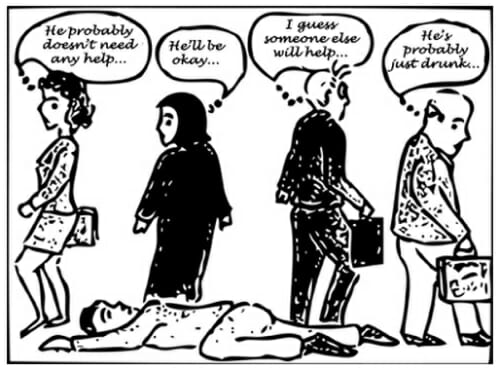

The Bystander Effect

Social psychology is the study of how people behave in social situations, so it deals with the complex interactions between personality, culture, and social pressures on how we behave and in turn are affected by each other. I took a social psychology course in college and it really opened my eyes. This was one of the first courses I took that challenged my assumptions in a profound way, because there is a disconnect between our assumptions about how people think and behave and how they actual do when objectively observed. In this way social psychology (and psychology in general) is an important pillar of scientific skepticism.

Social psychology is the study of how people behave in social situations, so it deals with the complex interactions between personality, culture, and social pressures on how we behave and in turn are affected by each other. I took a social psychology course in college and it really opened my eyes. This was one of the first courses I took that challenged my assumptions in a profound way, because there is a disconnect between our assumptions about how people think and behave and how they actual do when objectively observed. In this way social psychology (and psychology in general) is an important pillar of scientific skepticism.

As an example, there is a recent study that uses CCTV to monitor violent incidents in three cities, Amsterdam, Lancaster, and Cape Town. So these are real-life events, not staged for the study. The researchers counted how many times people intervened in such incidents, such as someone being pummeled on the ground by an attacker. First, think how you would respond in such a situation. Now also think about how the average person would respond. What percentage of the time do you think a bystander intervened? Was it the same or different in the various cities, which differ in terms of their crime and safety? If individuals fail to respond, why?

Your answers to these questions probably say more about you and the culture you live in than reality. This is the meta-finding of social psychology. We often are incorrect in our assumptions about what other people think, how other people behave, and what motivates other people. We also judge ourselves by a different set of rules than we judge others (the fundamental attribution error). Research also finds that understanding this is extremely empowering, and this is also something I found fascinating about social psychology. This was the first time I can remember that a little bit of knowledge empowered me to take greater control of my actions, rather than ride passively down the currents of subconscious psychological forces.

I am deliberately putting the link to the study and the results below the fold. When you’re ready, take a look.

Here is a summary of the study. Are you surprised to learn that in >90% of the recorded incidents a bystander intervened? Interventions include pulling the attacker off the victim, getting between them, trying to calm the aggressor down, or looking after the victim. Further, the rate was no different among the three cities, so this seems to be a fairly generalizable effect.

The study did also confirm what has long been demonstrated and known as the bystander effect. Specifically, the more bystanders are present during an emergency, the less likely it is that any individual will initiate action. However, this also means that there are a larger number of individuals, so the probability that any one of them will take action remains high. This effect was first researched after a famous incident in 1964 – Kitty Genovese was attacked outside her apartment building for 45 minutes, and eventually died. There were 38 residents who could see and hear the attack from their apartment, but no one reacted. This was a dramatic case, and affects how many people think of the bystander effect.

(This is how the incident was reported at the time, but later journalistic follow up found that the events were quite different. Only two people witnessed the event but failed to respond, one person shouted off the initial attack, and another called the police when finding the victim. The others were not aware of the attack.)

But again it’s important to realize that most people predict they would respond in such a situation, and yet most do not and so are probably incorrect in their prediction. The obvious question, then, is why do people often fail to respond to an emergency? The research suggests this is primarily due to diffusion of responsibility. In such a situation there are various competing motivations that people are trying to sort through, probably quickly in an unexpected situation that they may have not encountered before. Most people want to help, want to think of themselves as good people, and who wouldn’t want to play the hero. But we also may fear for our own safety. Further, there may be uncertainty about what is actually happening and if we can do anything. This may further lead to a fear of social embarrassment – if we intervene and discover we misread the situation, that could be awkward. So – if other people are present we calculate that someone else is likely to intervene, and therefore we are absolved of having to resolve our psychological dilemma.

We also tend to follow what other people do – we take our social cues from those around us. So if other people are not intervening, we assume that’s appropriate. We don’t want to be the first. Maybe they know something you don’t. But, as soon as one person does intervene, then others are more likely to join in. The social ice has been broken, and now everyone has permission to be the helpful neighbor and good person they see themselves to be. All this social uncertainty can be paralyzing, and sometimes these moments come and go quickly as we walk by, without time for the social algorithms in our heads to achieve resolution.

The recent study was consistent with all this also. When one person did intervene, others were likely to join in. When there were more bystanders someone was more likely to intervene, which could partly be due to the fact that in a potentially dangerous situation there is some safety in numbers.

So, how does all this affect us as individuals. I will give you an anecdote. Shortly after taking my social psychology course and learning about the bystander effect, I was walking on a busy Baltimore street and saw a man on his knees apparently struggling to get up. There were many people standing around or walking by and doing nothing. The situation was a bit ambiguous – was he looking for something? Did he need help? This ambiguity causes social fear. But, armed with my new knowledge of psychology I approached the man and asked if he needed help. He did. He was unable to stand on his own, and I was easily able to help him.

And, perhaps more interestingly, as soon as I did this several other bystanders who were close by jumped in and also offered to help. I could tell they felt a little guilty of being the bystander, but were paralyzed by their uncertainty, which I had just broke for them. It went just like the textbooks said it should. This social psychology stuff really works.

The deeper lesson here, one I take every opportunity to repeat in this blog, is that knowledge of how our own brains work is extremely empowering. Bystanders don’t necessarily consciously realize that uncertainty combined with fear of social faux pas facilitated by diffusion of responsibility is paralyzing them. But if you do know this, you can cut through it all and do the right thing, which is really the thing you want to do anyway. This applies to much of psychology and all of critical thinking. The more aware we are of how human cognition works, the more in control of ourselves and our thinking we will be.