May 28 2021

New Dark Matter Map Mystery

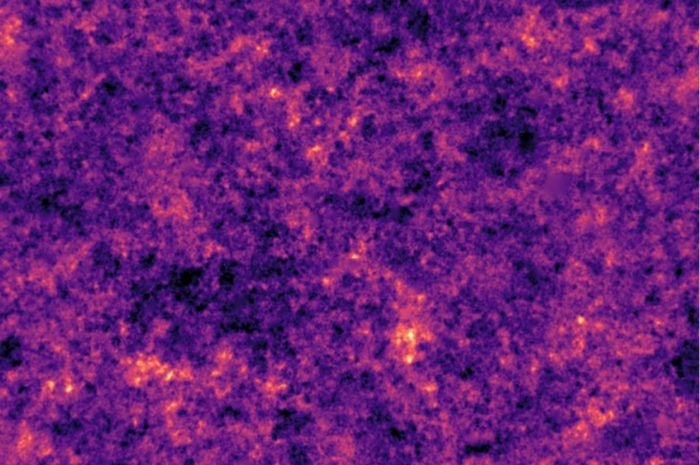

Scientists have published the most extensive map of dark matter in the universe to date, based on a survey of 100 million galaxies. The findings don’t quite match with predictions made by computer models, suggesting that there is some physics at work which scientists do not yet understand. This, of course, is exciting for physicists.

Scientists have published the most extensive map of dark matter in the universe to date, based on a survey of 100 million galaxies. The findings don’t quite match with predictions made by computer models, suggesting that there is some physics at work which scientists do not yet understand. This, of course, is exciting for physicists.

As I discussed previously, we don’t know what dark matter is, but we are pretty confident it’s there. Dark matter does not give off any radiation, but it does have gravity, so we can see its gravitational effects. Based on these observations it seems that 80% of the matter in the universe is dark matter. This is a major area of research, because we do not know what dark matter is made of. It is probably some new particle we have not identified so far. This is where scientists live – on the edge of our current knowledge, peering into the unknown.

Part of that “peering” is gathering lots of data, and that is what the current study does. They used gravitational lensing to map the gravity of the universe, 80% of which is dark matter. Visible galaxies and dark matter cluster together, creating an overall structure to the universe. There are vast black voids with nothing, and there are tendrils of matter with galaxies, gas, and stars. The goal is to map this distribution, to see where all the stuff in the universe is.

They then compared this map to what we would predict based on our current understanding of the laws of physics. They started with a map of where all the matter was 350,000 years after the Big Bang, which was created by examining the cosmic background radiation. Then they model where that matter should have gone over the last 13.8 billion years based upon relativity and other physical laws. The map and the model were off by a few percent. The universe is more evenly distributed than the models predict. This may not sound like a lot, but physicists are used to dealing with high levels of precision. Physical laws tend to be very reliable. This is why we can make calculations and send a probe to Pluto 5 billion km away, and arrive precisely where they predicted. If the New Horizons probe was off course by a few percent, that would have been a disaster, both for the mission and our understanding of the relevant laws of physics.

This is why physicists love discrepancies between predicted and observed phenomena, even tiny ones. It means something is going on we are not aware of. This could be an effect we have not considered, an error in their experimental design or method of observation, or occasionally a tweak to our understanding of the laws of physics. The first two need to be thoroughly ruled out before new physics can be confidently postulated, and it is an increasingly rare event, but that is what physicists live for.

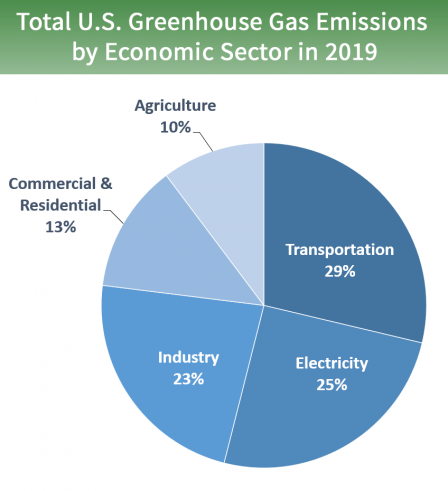

There have been many studies coming out recently looking at what it would take to mitigate climate change, and some patterns emerge from these analyses. First it is important to note that a certain amount of climate change has already happened,

There have been many studies coming out recently looking at what it would take to mitigate climate change, and some patterns emerge from these analyses. First it is important to note that a certain amount of climate change has already happened,

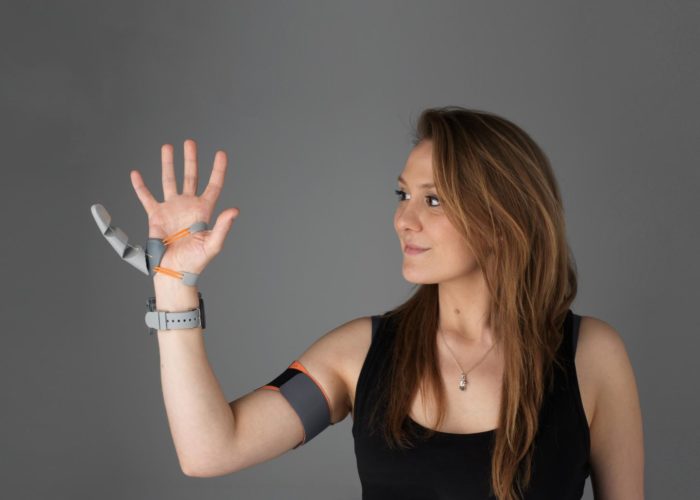

Imagine having an extra arm, or an extra thumb on one hand, or even a tail, and imagine that it felt like a natural part of your body and you could control it easily and dexterously. How plausible is this type of robotic augmentation? Could “Doc Oc” really exist?

Imagine having an extra arm, or an extra thumb on one hand, or even a tail, and imagine that it felt like a natural part of your body and you could control it easily and dexterously. How plausible is this type of robotic augmentation? Could “Doc Oc” really exist? As project Artemis proceeds with plans not only to return to the Moon, but to produce the infrastructure for a long term presence, we need to deal with the issue of solar storms. If you haven’t seen the series, For All Mankind, I highly recommend it. In one episode they dramatize the effects of a particularly strong solar storm. I don’t think the special effects were accurate (the moon dust would not have kicked up like that) but the risk to human life was. If Artemis is going to be successful, we will need to be able to protect astronauts from these storms and the background radiation and be better able to predict them.

As project Artemis proceeds with plans not only to return to the Moon, but to produce the infrastructure for a long term presence, we need to deal with the issue of solar storms. If you haven’t seen the series, For All Mankind, I highly recommend it. In one episode they dramatize the effects of a particularly strong solar storm. I don’t think the special effects were accurate (the moon dust would not have kicked up like that) but the risk to human life was. If Artemis is going to be successful, we will need to be able to protect astronauts from these storms and the background radiation and be better able to predict them. The term “bullshitting” (in addition to its colloquial use) is a technical psychological term that means, “communication characterised by an intent to be convincing or impressive without concern for truth.” This is not the same as lying, in which one knows what they are saying is false. Bullshitters simply are indifferent to whether or not what they say is true. Their speech is optimized for sounding impressive, not accuracy. I have discussed before research showing that people who are more receptive to

The term “bullshitting” (in addition to its colloquial use) is a technical psychological term that means, “communication characterised by an intent to be convincing or impressive without concern for truth.” This is not the same as lying, in which one knows what they are saying is false. Bullshitters simply are indifferent to whether or not what they say is true. Their speech is optimized for sounding impressive, not accuracy. I have discussed before research showing that people who are more receptive to

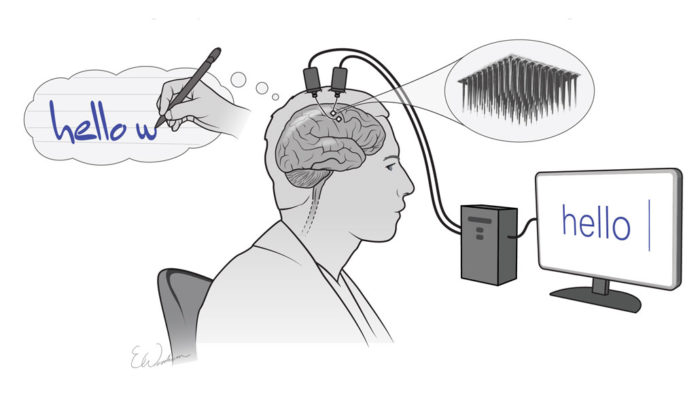

We have another incremental advance with brain-machine interface technology, and one with practical applications.

We have another incremental advance with brain-machine interface technology, and one with practical applications.  Technology is often interdependent. Electric cars are dependent on battery technology. Tall skyscrapers were not possible without the elevator. Modern rocketry requires computer technology. And the promise of fusion reactors is largely dependent on our ability to make really powerful magnets. Recent progress in powerful magnet technology may be moving us closer to the reality of commercial fusion.

Technology is often interdependent. Electric cars are dependent on battery technology. Tall skyscrapers were not possible without the elevator. Modern rocketry requires computer technology. And the promise of fusion reactors is largely dependent on our ability to make really powerful magnets. Recent progress in powerful magnet technology may be moving us closer to the reality of commercial fusion.