Jul

10

2023

A recent New York Times article tries to rehabilitate the reputation of Uri Geller, famed spoon-bending magician, by simply telling a one-sided narrative. From my perspective as a skeptic, this was a terrible article that missed the real issue, glossed over glaring defects in Geller’s behavior, and essentially just apologized for fraud. I know my perspective is not always mainstream, at least when it comes to popular culture, but shouldn’t good journalism at least represent all sides fairly? This piece was the equivalent of covering a contentious political topic only from the perspective of one political party.

A recent New York Times article tries to rehabilitate the reputation of Uri Geller, famed spoon-bending magician, by simply telling a one-sided narrative. From my perspective as a skeptic, this was a terrible article that missed the real issue, glossed over glaring defects in Geller’s behavior, and essentially just apologized for fraud. I know my perspective is not always mainstream, at least when it comes to popular culture, but shouldn’t good journalism at least represent all sides fairly? This piece was the equivalent of covering a contentious political topic only from the perspective of one political party.

Uri Geller is a magician who came to fame in the 1970s as a spoon-bender. He became what all entertainers hope to become – a pop-culture figure that is larger than life. I would argue that it was partly spoon-bending as a phenomenon (the idea of bending cutlery with one’s mind alone) that became a true pop-culture icon, but Geller was the face of spoon-bending. Geller, no doubt, became famous and wealthy off his schtick. He sold it well, and successfully.

But here is the controversy surrounding Geller – was he being unethical in terms of the degree to which he presented himself, not as a magician, but as a true psychic? It is pretty clear (in my opinion – don’t sue me, Geller), that Geller is nothing but a stage magician. He is using tricks that any skilled magician can do. As James Randi was fond of saying, if Geller is using real magic to achieve his results, then he’s doing it the hard way. Randi stated it this way, because Geller sued him for defamation (three times) when Randi said that Geller was using magic tricks.

Continue Reading »

May

16

2023

I have been writing blog posts and engaging in science communication long enough that I have a pretty good sense how much engagement I am going to get from a particular topic. Some topics are simply more divisive than others (although there is an unpredictable element from social media networks). I wish I could say that the more scientifically interesting topics garnered more attention and comments, but that is not the case. The overall pattern is that topics which have an ideological angle or affect people’s world-view inspire more passionate criticism or defense. Timed drug release is an important topic, with implications for potentially anyone who has to take medication at some point in their lives. But it doesn’t challenge anyone’s world view. ESP, on the other hand, is a fringe topic likely to directly affect no one, but apparently is 70 times more interesting to my readers (using comments as a measure).

I have been writing blog posts and engaging in science communication long enough that I have a pretty good sense how much engagement I am going to get from a particular topic. Some topics are simply more divisive than others (although there is an unpredictable element from social media networks). I wish I could say that the more scientifically interesting topics garnered more attention and comments, but that is not the case. The overall pattern is that topics which have an ideological angle or affect people’s world-view inspire more passionate criticism or defense. Timed drug release is an important topic, with implications for potentially anyone who has to take medication at some point in their lives. But it doesn’t challenge anyone’s world view. ESP, on the other hand, is a fringe topic likely to directly affect no one, but apparently is 70 times more interesting to my readers (using comments as a measure).

I also get e-mails, and my recent article on ESP research attracted a number of angry individuals who wanted to excoriate my closed minded “scientism”. I think people care so much about ESP and other psi and paranormal phenomena because it gets at the heart of their beliefs about reality – do we live in a purely naturalistic and mechanistic world, or do we live in a world where the supernatural exists? Further, in my experience while many people are happy to praise the virtue of faith (believing without knowing) in reality they desperately want there to be objective evidence for their beliefs. Meanwhile, I think it’s fair to say that a dedicated naturalist would find it “disturbing” (if I can paraphrase Darth Vader) if there really were convincing evidence that contradicts naturalism. Both sides have an out, as it were. Believers in a supernatural universe can always say that the supernatural by definition is not provable by science. One can only have faith. This is a rationalization that has the virtue of being true, if properly formulated and utilized. Naturalists can also say that if you have actual scientific evidence of an alleged paranormal phenomenon, then by definition it’s not paranormal. It just reflects a deeper reality and points in the direction of new science. Yeah!

Regardless of what you believe deep down about the ultimate nature of reality (and honestly, I couldn’t care less, as long as you don’t think you have the right to impose that view on others), the science is the science. Science follows methodological naturalism, and is agnostic toward the supernatural question. It operates within a framework of naturalism, but recognizes this is a construct, and does not require philosophical naturalism. So you can have your faith, just don’t mess with science.

Continue Reading »

May

01

2023

I was interviewed recently for a Daily Beast article on recent research involving the Institute of Noetic Sciences (IONS). Overall the article is very good, and author Maddie Bender was fair and reasonable in how I was quoted. I can’t always take that as a given. No matter how careful you are, a lot can be done with the edit and perfectly reasonable statements can be framed in a positive or negative light. It all depends on what story the author is writing.

I was interviewed recently for a Daily Beast article on recent research involving the Institute of Noetic Sciences (IONS). Overall the article is very good, and author Maddie Bender was fair and reasonable in how I was quoted. I can’t always take that as a given. No matter how careful you are, a lot can be done with the edit and perfectly reasonable statements can be framed in a positive or negative light. It all depends on what story the author is writing.

In this case the story was about how fringe science and even pseudoscience can infiltrate mainstream academic institutions. There is a lot of nuance to this topic, because as with many such things there is a demarcation problem. As I have discussed many times before, for example, there is a demarcation problem between science and pseudoscience. There is no sharp line between the two, but a smooth transition. Much mainstream science can fall short in terms of rigorous methodology, and not all pseudoscience gets everything wrong. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t pseudoscience (that would be the false continuum logical fallacy) – get far enough to one end of the spectrum and you are in the realm of pseudoscience.

Academic institutions have another demarcation problem to deal with – academic freedom. This one is perhaps even trickier, because it is critically important that academics have the intellectual freedom to explore new and unpopular ideas, even ones that may be considered “dangerous”. As I have also written before, I have no problem with researchers exploring new ideas, fringe ideas, even weird ideas, as long as they are being true to scientific philosophy and methodology, and not making claims that go beyond the evidence. Further, this means that pseudoscience is not an area of study, but a set of behaviors. You can be doing pseudoscience when studying mainstream claims, or rigorous science when studying the paranormal. It’s the method and logic that matter. For example, Richard Wiseman has done rigorous investigations of the paranormal. I would never call him a pseudoscientist.

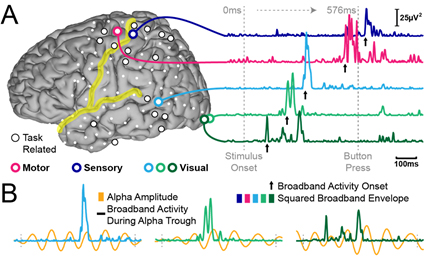

One of the core features of doing pseudoscience is assuming that your claim (paranormal or otherwise) is true and then working backwards from that assumption. This leads to performing research to show that the phenomenon is true, or perhaps how it works, but not doing research capable of determine if it is true. This brings us back to IONS and the Daily Beast article. The article focuses on neuroscientist Spiro Pantazatos and his collaboration with IONS, looking for brain regions that might correlate with specific paranormal phenomena. My problem with this research is that is assumes various paranormal phenomena are real, when that has not been scientifically established. In fact, as I point out in the article, we have over a century of research which has failed to demonstrate psi phenomena (ESP, clairvoyance, telekenesis, etc.) to point to. This is not some new idea that has never been explored.

Continue Reading »

Nov

07

2022

The notion of near death experiences (NDE) have fascinated people for a long time. The notion is that some people report profound experiences after waking up from a cardiac arrest – their heart stopped, they received CPR, they were eventually recovered and lived to tell the tale. About 20% of people in this situation will report some unusual experience. Initial reporting on NDEs was done more from a journalistic methodology than scientific – collecting reports from people and weaving those into a narrative. Of course the NDE narrative took on a life of it’s own, but eventually researchers started at least collecting some empirical quantifiable data. The details of the reported NDEs are actually quite variable, and often culture-specific. There are some common elements, however, notably the sense of being out of one’s body or floating.

The notion of near death experiences (NDE) have fascinated people for a long time. The notion is that some people report profound experiences after waking up from a cardiac arrest – their heart stopped, they received CPR, they were eventually recovered and lived to tell the tale. About 20% of people in this situation will report some unusual experience. Initial reporting on NDEs was done more from a journalistic methodology than scientific – collecting reports from people and weaving those into a narrative. Of course the NDE narrative took on a life of it’s own, but eventually researchers started at least collecting some empirical quantifiable data. The details of the reported NDEs are actually quite variable, and often culture-specific. There are some common elements, however, notably the sense of being out of one’s body or floating.

The most rigorous attempt so far to study NDEs was the AWARE study, which I reported on in 2014. Lead researcher Sam Parnia, wanted to be the first to document that NDEs are a real-world experience, and not some “trick of the brain.” He failed to do this, however. The study looked at people who had a cardiac arrest, underwent CPR, and survived long enough to be interviewed. The study also included a novel element – cards placed on top of shelves in ERs around the country. These can only been seen from the vantage point of someone floating near the ceiling, meant to document that during the CPR itself an NDE experiencer was actually there and could see the physical card in their environment. The study also tried to match the details of the remembered experience with actual events that took place in the ER during their CPR.

You can read my original report for details, but the study was basically a bust. There were some methodological problems with the study, which was not well-controlled. They had trouble getting data from locations that had the cards in place, and ultimately had not a single example of a subject who saw a card. And out of 140 cases they were only able to match reported details with events in the ER during CPR in one case. Especially given that the details were fairly non-specific, and they only had 1 case out of 140, this sounds like random noise in the data.

Continue Reading »

Aug

23

2021

In the early days of my skeptical activism I and my colleagues often took on some of the classics of pseudoscience, such as UFOs, dowsing, astrology, and ghost-hunting. As a New England-based group we also focused on local pseudoscience, which means ghosts and ghost-hunting. By coincidence we had perhaps the most famous ghost hunters in the world living just a couple towns over from us, Ed and Lorraine Warren. They were made famous by the Amityville Horror case, and more recently by The Conjuring series of movies.

In the early days of my skeptical activism I and my colleagues often took on some of the classics of pseudoscience, such as UFOs, dowsing, astrology, and ghost-hunting. As a New England-based group we also focused on local pseudoscience, which means ghosts and ghost-hunting. By coincidence we had perhaps the most famous ghost hunters in the world living just a couple towns over from us, Ed and Lorraine Warren. They were made famous by the Amityville Horror case, and more recently by The Conjuring series of movies.

Even 23 years ago, when we encountered the Warrens, they were famous. They made the college circuit with their talks and slide-shows, held ghost-hunting classes, and spawned dozens of breakaway groups over the years. They were clearly the big fish in our little pond, and so we didn’t know what quite to expect when they agreed to allow us to interview and then investigate them. I want to stress this was a collaborative endeavor throughout, although they certainly weren’t happy with our final conclusions.

On our initial visit Ed gave us a tour of his basement museum, which he claimed was the most haunted place in the world. It included that Raggedy Ann doll that is now the focus of The Conjuring movies, which was kept behind a glass case with a stern warning not to open. I was amused that the collection of haunted items includes a D&D handbook, the Unearthed Arcana. We also asked Ed to show us his best piece of evidence after years of hunting ghosts, and without any hesitation he said it was his video of the White Lady of Union Cemetery. This video has now been digitized and uploaded to Youtube, so you can see for yourself what Ed considered his best evidence.

Continue Reading »

Jan

26

2021

Some spiritualists claim to be “clairaudient” which means they can hear voices, usually of spirits of the the dead. Some claim to be clairvoyant, which means they can see things remotely (from a different place and/or time), while still others claim clairsentience, meaning that they can feel emotions or sensations from objects or places. There is no credible scientific evidence that any of this is real, meaning that they represent genuine extrasensory perception (ESP), or the perception of genuine external information through non-physical (or at least unknown) means. There is also no plausible mechanism for such phenomena. This doesn’t make such phenomena strictly impossible, just highly unlikely, and sets a very high bar for evidence to be convinced they are real.

Some spiritualists claim to be “clairaudient” which means they can hear voices, usually of spirits of the the dead. Some claim to be clairvoyant, which means they can see things remotely (from a different place and/or time), while still others claim clairsentience, meaning that they can feel emotions or sensations from objects or places. There is no credible scientific evidence that any of this is real, meaning that they represent genuine extrasensory perception (ESP), or the perception of genuine external information through non-physical (or at least unknown) means. There is also no plausible mechanism for such phenomena. This doesn’t make such phenomena strictly impossible, just highly unlikely, and sets a very high bar for evidence to be convinced they are real.

When a person claims to hear, see, or feel something through ESP, then, what is happening? Likely, many different things. In some cases there is good reason to suspect (or there is even solid evidence) that the person is simply lying. Convincing others that you have special access to hidden knowledge can be lucrative. But assuming that in at least some cases the person claiming to experience ESP is sincere, what is happening? (And to be clear, this is not a strict dichotomy, as there is a full spectrum of people mixing sincere belief with “shortcuts”.) Is this all a learned behavior, or are some people neurologically or psychologically predisposed to the subjective experience of ESP?

Continue Reading »

Oct

20

2020

In 2011 Daryl Bem published a series of ten studies which he claimed demonstrated psi phenomena – that people could “feel the future”. He took standard psychological study methods and simply reversed the order of events, so that the effect was measured prior to the stimulus. Bem claimed to find significant results – therefore psi is real. Skeptics and psychologists were not impressed, for various reasons. At the time, I wrote this:

In 2011 Daryl Bem published a series of ten studies which he claimed demonstrated psi phenomena – that people could “feel the future”. He took standard psychological study methods and simply reversed the order of events, so that the effect was measured prior to the stimulus. Bem claimed to find significant results – therefore psi is real. Skeptics and psychologists were not impressed, for various reasons. At the time, I wrote this:

Perhaps the best thing to come out of Bem’s research is an editorial to be printed with the studies – Why Psychologists Must Change the Way They Analyze Their Data: The Case of Psi by Eric Jan Wagenmakers, Ruud Wetzels, Denny Borsboom, & Han van der Maas from the University of Amsterdam. I urge you to read this paper in its entirety, and I am definitely adding this to my filing cabinet of seminal papers. They hit the nail absolutely on the head with their analysis.

Their primary point is this – when research finds positive results for an apparently impossible phenomenon, this is probably not telling us something new about the universe, but rather is probably telling us something very important about the limitations of our research methods

I interviewed Wagenmakers for the SGU, and he added some juicy tidbits. For example, Bem had previously authored a chapter in a textbook on research methodology in which he essentially advocated for p-hacking. This refers to a set of bad research methods that gives the researchers enough wiggle room to fudge the results, enough to make negative data seem statistically significant. This could be as seemingly innocent as deciding when to stop collecting data after you have already peeked at some of the results.

Richard Wiseman, who was one of the first psychologists to try to replicate Bem’s research and came up with negative results, recently published a paper discussing this very issue. In his blog post about the article he credits Bem’s research with being a significant motivator for improving research rigor in psychology:

Several researchers noted that the criticisms aimed at Bem’s work also applied to many studies from mainstream psychology. Many of the problems surrounded researchers changing their statistics and hypotheses after they had looked at their data, and so commentators urged researchers to submit a detailed description of their plans prior to running their studies. In 2013, psychologist Chris Chambers played a key role in getting the academic journal Cortex to adopt the procedure (known as a Registered Report), and many other journals quickly followed suit.

Continue Reading »

Jan

03

2019

Magicians play a significant role in the skeptical movement. They have, as Liam Neeson famously said, a particular set of skills. They are very adept at deception, using techniques that have been honed through trial and error over centuries. It is a great example of cultural knowledge. Having the ability to deceive others, purely for entertainment and with informed consent, also makes them adept at detecting the use of the same techniques for nefarious purposes. This, essentially, has been James Randi’s entire career.

Magicians play a significant role in the skeptical movement. They have, as Liam Neeson famously said, a particular set of skills. They are very adept at deception, using techniques that have been honed through trial and error over centuries. It is a great example of cultural knowledge. Having the ability to deceive others, purely for entertainment and with informed consent, also makes them adept at detecting the use of the same techniques for nefarious purposes. This, essentially, has been James Randi’s entire career.

But at the same time some stage magicians make skeptics uncomfortable by not being entirely upfront with their audience. Now, I am not suggesting that all magicians tell their audience how the tricks are done, and I completely understand the need to create a mystique as part of the performance. However, I have seen skilled magicians (like Randi or Banachek) perform amazing tricks with complete candor about the nature of those tricks, without diminishing the entertainment value.

Magicians typically create a narrative by which they “explain” their tricks to the audience. A magician, for example, could say, “I am using sleight of hand.” Or they could say (or strongly imply), “I have true psychic ability.” The Amazing Kreskin falls into this latter category. There are also those like Uri Geller who (sort of) pretend they are not doing magic at all, but have special powers.

In the gray zone are those like Derren Brown. Their narrative is not that they are psychic but that they are using psychological manipulation on their audience – reading microexpressions, influencing their decision-making, or reading body-language. This narrative is as much BS as the psychic one, used as part of the magic experience and for misdirection. You can read and influence people to some degree, but these techniques are not reliable enough to support a performance. Typically mentalists use standard sleight of hand and then pretend to use psychological techniques.

Continue Reading »

Aug

16

2018

There is no question that people occasionally have strange experiences, sometimes very strange. There is a tendency to interpret such experiences as external, reflecting something happening in the world, rather than internal, reflecting something happening in our brains.

There is no question that people occasionally have strange experiences, sometimes very strange. There is a tendency to interpret such experiences as external, reflecting something happening in the world, rather than internal, reflecting something happening in our brains.

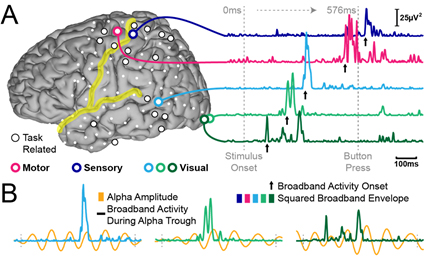

Neuroscience, however, has provided us a powerful tool for understanding some of these experiences. They are a window into how our brains construct our experience of reality, and what we experience when that process breaks down or is altered by drugs, trauma, electrical stimulation, oxygen deprivation, or other stressors.

A recent study looking at the hallucinogen DMT (N,N-Dimethyltryptamine) adds an interesting insight into our collective knowledge of these altered states of consciousness. The researchers studied 13 healthy volunteers, who were given placebo, and then in a separate session a week later DMT, and extensively questioned about their experiences. The researchers specifically wanted to test the possibility that a DMT-induced hallucination would be similar to reported near-death experiences.

In short they found that the DMT experiences were extremely similar to near-death experiences (NDE), but let’s look at the details.

They gave the subjects an established NDE scale, which assesses for 16 features reported by those who experience an NDE. A score of 7 or higher is considered to be a genuine NDE. All 13 subjects scored 7 or higher on this scale when given DMT. Ten of the 16 features were statistically more likely during DMT than placebo. And the total scores were similar to a historical control group of reported NDEs. So again – DMT produced an experience that was very similar to reported NDEs.

Continue Reading »

Mar

19

2018

In the 1970s and 80s belief in the paranormal was the most common target of skeptics. Topics like extrasensory perception (ESP), astrology, and faith healing were at the top of the list of skeptical concerns. In the last 30 years skepticism has evolved quite a bit, and while we never stopped being watchdogs on paranormal beliefs and other pseudosciences, they did mostly fade into the background. Other topics, such as science denial and the rise of fake news, took center stage.

In the 1970s and 80s belief in the paranormal was the most common target of skeptics. Topics like extrasensory perception (ESP), astrology, and faith healing were at the top of the list of skeptical concerns. In the last 30 years skepticism has evolved quite a bit, and while we never stopped being watchdogs on paranormal beliefs and other pseudosciences, they did mostly fade into the background. Other topics, such as science denial and the rise of fake news, took center stage.

But history has shown that there is often a cycle to such things. Interest in UFOs has waxed and waned over the years, for example, never going away completely, but fading and then rising again to prominence as a new generation discovers the topic.

Still, we do like to think we are making some progress through exposure and education. We have tried to interact frequently with the press so that at least the skeptical point of view will get better exposure when such topics are addressed. One solid victory was when the BBC announced they will no longer follow a pattern of false balance when dealing with science denial – putting a crank up against the consensus of scientific opinion as if they were equal.

A recent episode of CBS Sunday Morning about ESP, however, was worse than false balance, it was a throwback to the early days of credulous reporting about the paranormal with only token skepticism. Not that token skepticism was gone, but it has become more rare, especially from a major network or news outlet.

The piece, by Erin Moriarty, is a complete journalistic fail. It was the kind of piece we used to see thirty plus years ago before the skeptical movement had any traction. It is a perfect example of what we call token skepticism – a piece that is utterly gullible except for a very brief talking head skeptic who says something generic, like, “There is no scientific evidence to support this.” The token skepticism is immediately negated, however, by some response from the true-believer, a response the skeptic is never allowed to respond to in turn.

Continue Reading »

A recent New York Times article tries to rehabilitate the reputation of Uri Geller, famed spoon-bending magician, by simply telling a one-sided narrative. From my perspective as a skeptic, this was a terrible article that missed the real issue, glossed over glaring defects in Geller’s behavior, and essentially just apologized for fraud. I know my perspective is not always mainstream, at least when it comes to popular culture, but shouldn’t good journalism at least represent all sides fairly? This piece was the equivalent of covering a contentious political topic only from the perspective of one political party.

A recent New York Times article tries to rehabilitate the reputation of Uri Geller, famed spoon-bending magician, by simply telling a one-sided narrative. From my perspective as a skeptic, this was a terrible article that missed the real issue, glossed over glaring defects in Geller’s behavior, and essentially just apologized for fraud. I know my perspective is not always mainstream, at least when it comes to popular culture, but shouldn’t good journalism at least represent all sides fairly? This piece was the equivalent of covering a contentious political topic only from the perspective of one political party.

I have been writing blog posts and engaging in science communication long enough that I have a pretty good sense how much engagement I am going to get from a particular topic. Some topics are simply more divisive than others (although there is an unpredictable element from social media networks). I wish I could say that the more scientifically interesting topics garnered more attention and comments, but that is not the case. The overall pattern is that topics which have an ideological angle or affect people’s world-view inspire more passionate criticism or defense. Timed drug release is an important topic, with implications for potentially anyone who has to take medication at some point in their lives. But it doesn’t challenge anyone’s world view. ESP, on the other hand, is a fringe topic likely to directly affect no one, but apparently is 70 times more interesting to my readers (using comments as a measure).

I have been writing blog posts and engaging in science communication long enough that I have a pretty good sense how much engagement I am going to get from a particular topic. Some topics are simply more divisive than others (although there is an unpredictable element from social media networks). I wish I could say that the more scientifically interesting topics garnered more attention and comments, but that is not the case. The overall pattern is that topics which have an ideological angle or affect people’s world-view inspire more passionate criticism or defense. Timed drug release is an important topic, with implications for potentially anyone who has to take medication at some point in their lives. But it doesn’t challenge anyone’s world view. ESP, on the other hand, is a fringe topic likely to directly affect no one, but apparently is 70 times more interesting to my readers (using comments as a measure). I was interviewed recently for

I was interviewed recently for  The notion of near death experiences (NDE) have fascinated people for a long time. The notion is that some people report profound experiences after waking up from a cardiac arrest – their heart stopped, they received CPR, they were eventually recovered and lived to tell the tale. About 20% of people in this situation will report some unusual experience. Initial reporting on NDEs was done more from a journalistic methodology than scientific – collecting reports from people and weaving those into a narrative. Of course the NDE narrative took on a life of it’s own, but eventually researchers started at least collecting some empirical quantifiable data. The details of the reported NDEs are actually quite variable, and often culture-specific. There are some common elements, however, notably the sense of being out of one’s body or floating.

The notion of near death experiences (NDE) have fascinated people for a long time. The notion is that some people report profound experiences after waking up from a cardiac arrest – their heart stopped, they received CPR, they were eventually recovered and lived to tell the tale. About 20% of people in this situation will report some unusual experience. Initial reporting on NDEs was done more from a journalistic methodology than scientific – collecting reports from people and weaving those into a narrative. Of course the NDE narrative took on a life of it’s own, but eventually researchers started at least collecting some empirical quantifiable data. The details of the reported NDEs are actually quite variable, and often culture-specific. There are some common elements, however, notably the sense of being out of one’s body or floating. In the early days of my skeptical activism I and my colleagues often took on some of the classics of pseudoscience, such as UFOs, dowsing, astrology, and ghost-hunting. As a New England-based group we also focused on local pseudoscience, which means ghosts and ghost-hunting. By coincidence we had perhaps the most famous ghost hunters in the world living just a couple towns over from us, Ed and Lorraine Warren. They were made famous by the Amityville Horror case, and more recently by The Conjuring series of movies.

In the early days of my skeptical activism I and my colleagues often took on some of the classics of pseudoscience, such as UFOs, dowsing, astrology, and ghost-hunting. As a New England-based group we also focused on local pseudoscience, which means ghosts and ghost-hunting. By coincidence we had perhaps the most famous ghost hunters in the world living just a couple towns over from us, Ed and Lorraine Warren. They were made famous by the Amityville Horror case, and more recently by The Conjuring series of movies. Some spiritualists claim to be “clairaudient” which means they can hear voices, usually of spirits of the the dead. Some claim to be clairvoyant, which means they can see things remotely (from a different place and/or time), while still others claim clairsentience, meaning that they can feel emotions or sensations from objects or places. There is no credible scientific evidence that any of this is real, meaning that they represent genuine extrasensory perception (ESP), or the perception of genuine external information through non-physical (or at least unknown) means. There is also no plausible mechanism for such phenomena. This doesn’t make such phenomena strictly impossible, just highly unlikely, and sets a very high bar for evidence to be convinced they are real.

Some spiritualists claim to be “clairaudient” which means they can hear voices, usually of spirits of the the dead. Some claim to be clairvoyant, which means they can see things remotely (from a different place and/or time), while still others claim clairsentience, meaning that they can feel emotions or sensations from objects or places. There is no credible scientific evidence that any of this is real, meaning that they represent genuine extrasensory perception (ESP), or the perception of genuine external information through non-physical (or at least unknown) means. There is also no plausible mechanism for such phenomena. This doesn’t make such phenomena strictly impossible, just highly unlikely, and sets a very high bar for evidence to be convinced they are real. In 2011 Daryl Bem

In 2011 Daryl Bem  Magicians play a significant role in the skeptical movement. They have, as Liam Neeson famously said, a particular set of skills. They are very adept at deception, using techniques that have been honed through trial and error over centuries. It is a great example of cultural knowledge. Having the ability to deceive others, purely for entertainment and with informed consent, also makes them adept at detecting the use of the same techniques for nefarious purposes. This, essentially, has been James Randi’s entire career.

Magicians play a significant role in the skeptical movement. They have, as Liam Neeson famously said, a particular set of skills. They are very adept at deception, using techniques that have been honed through trial and error over centuries. It is a great example of cultural knowledge. Having the ability to deceive others, purely for entertainment and with informed consent, also makes them adept at detecting the use of the same techniques for nefarious purposes. This, essentially, has been James Randi’s entire career. There is no question that people occasionally have strange experiences, sometimes very strange. There is a tendency to interpret such experiences as external, reflecting something happening in the world, rather than internal, reflecting something happening in our brains.

There is no question that people occasionally have strange experiences, sometimes very strange. There is a tendency to interpret such experiences as external, reflecting something happening in the world, rather than internal, reflecting something happening in our brains. In the 1970s and 80s belief in the paranormal was the most common target of skeptics. Topics like extrasensory perception (ESP), astrology, and faith healing were at the top of the list of skeptical concerns. In the last 30 years skepticism has evolved quite a bit, and while we never stopped being watchdogs on paranormal beliefs and other pseudosciences, they did mostly fade into the background. Other topics, such as science denial and the rise of fake news, took center stage.

In the 1970s and 80s belief in the paranormal was the most common target of skeptics. Topics like extrasensory perception (ESP), astrology, and faith healing were at the top of the list of skeptical concerns. In the last 30 years skepticism has evolved quite a bit, and while we never stopped being watchdogs on paranormal beliefs and other pseudosciences, they did mostly fade into the background. Other topics, such as science denial and the rise of fake news, took center stage.