May

18

2023

There is an ongoing culture war, and not just in the US, over the content of childhood education, both public and private. This seems to be flaring up recently, but is never truly gone. Republicans in the US have recently escalated this war by banning over 500 books in several states (mostly Florida) because they contain “inappropriate” content. There are a few issues worth exploring here.

There is an ongoing culture war, and not just in the US, over the content of childhood education, both public and private. This seems to be flaring up recently, but is never truly gone. Republicans in the US have recently escalated this war by banning over 500 books in several states (mostly Florida) because they contain “inappropriate” content. There are a few issues worth exploring here.

First, I think it is an important premise to recognize the value of public education. As educator Dana Mitra summarizes:

Research shows that individuals who graduate and have access to quality education throughout primary and secondary school are more likely to find gainful employment, have stable families, and be active and productive citizens. They are also less likely to commit serious crimes, less likely to place high demands on the public health care system, and less likely to be enrolled in welfare assistance programs. A good education provides substantial benefits to individuals and, as individual benefits are aggregated throughout a community, creates broad social and economic benefits.

Continue Reading »

May

15

2023

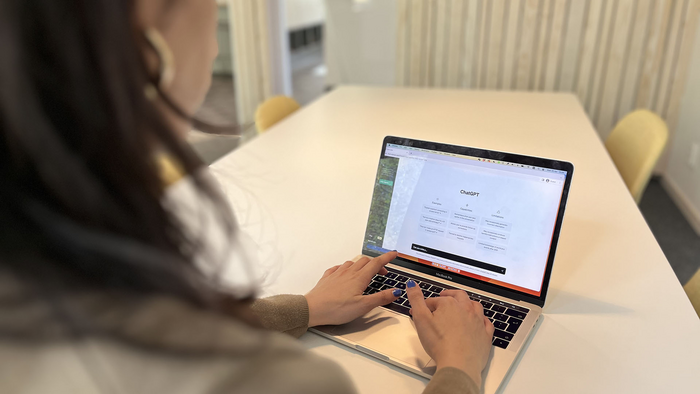

Researchers recently published an extensive survey of almost 6,000 students across academic institution in Sweden. The results are not surprising, but they do give a snapshot of where we are with the recent introduction of large language model AIs.

Researchers recently published an extensive survey of almost 6,000 students across academic institution in Sweden. The results are not surprising, but they do give a snapshot of where we are with the recent introduction of large language model AIs.

Most students, 56%, reported that they use Chat GPT in their studies, and 35% regularly. More than half do not know if their school has guidelines on AI use in their classwork, and 62% believe that using a chatbot during an exam is cheating (so 38% do not think that). What this means is that most students are using AI for their classwork, but they don’t know what the rules are and are unclear on what would constitute cheating. Also, almost half of students think that using AI makes them more efficient learners, and many commented that they feel it has improved their own language and thinking skills.

So – is the use of AI in education a bane or a boon? Of course, asking students is only one window into this question. Educators have concerns about AI creating a lazy student, that can serve up good-enough answers to get by. There are also concerns about outright cheating, although that has to be carefully defined. Some teachers don’t know how to react when students turn in essays that appear to have been written by a chat bot. But many also think there is tremendous potential is using AI as an educational tool.

Clearly the availability of the latest generation of large language model AIs is a disruptive technology. Schools are now scrambling to deal with it, but I think they have no choice. Students are moving fast, and if schools don’t keep up they will miss an opportunity and fail to mitigate the potential downsides. What is clear is that AI has the potential to significantly change education. Simplistic solutions like just banning the use of AI is not going to work.

Continue Reading »

Oct

27

2022

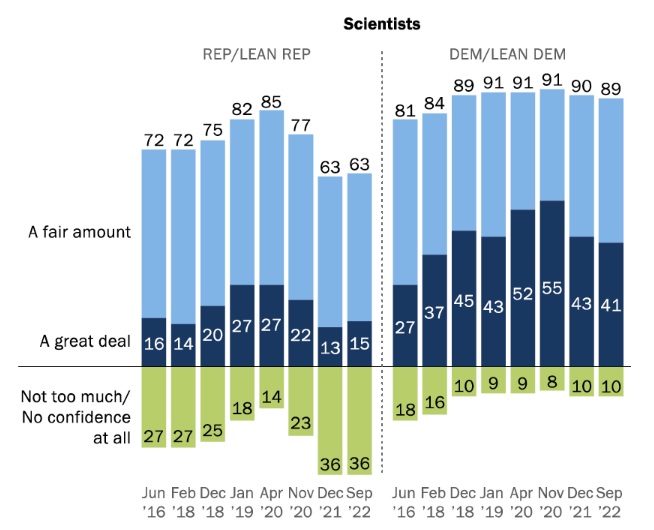

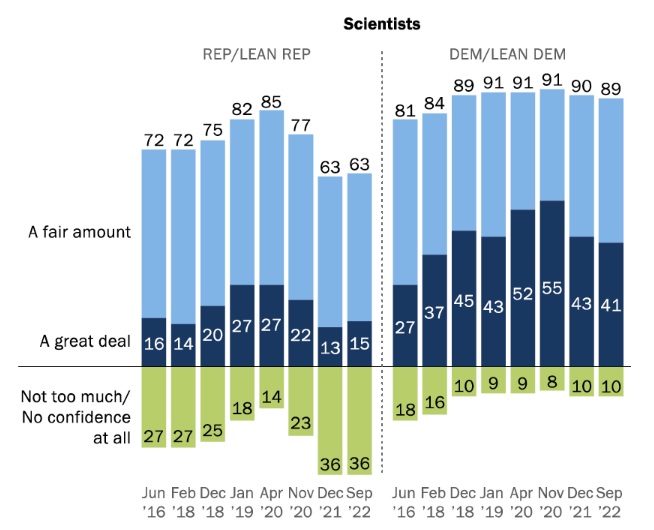

A new Pew survey updates their data on American’s trust in scientists. The “good news” is that overall, trust remains high, with 77% saying they trust scientists a great deal or a fair amount, and only 23% not too much or not at all. Actually, when you think about it these numbers are still pretty bad, but they seem good because our expectations are so low. More than one in five people don’t trust scientists. For more perspective, that 77% figure is the same for the military. The highest rated group was medical scientists at 80%. Elected officials were at 28%.

A new Pew survey updates their data on American’s trust in scientists. The “good news” is that overall, trust remains high, with 77% saying they trust scientists a great deal or a fair amount, and only 23% not too much or not at all. Actually, when you think about it these numbers are still pretty bad, but they seem good because our expectations are so low. More than one in five people don’t trust scientists. For more perspective, that 77% figure is the same for the military. The highest rated group was medical scientists at 80%. Elected officials were at 28%.

These numbers are also fairly stable over time. Interestingly they did bump up a bit during the pandemic, but then quickly returned to their historical levels. Some argue that these numbers are pretty good and we shouldn’t “freak out about the minority.” I disagree – not that we should freak out, but we do need to take these numbers seriously, and they are not necessarily good news.

One reason I am still concerned about these numbers is that there is a pretty significant partisan divide. Recent years have Democrats at around 90% with Republicans around 63%. More than a third of one major political party does not trust scientists, and they seem to be the political center of the party. This gets even worse if you look at the question of whether or not scientists should play an active role in policy debates. Only 66% of Democrats say yes, and only 29% of Republicans (down from 75 and 43 respectively). This, to me, is very telling. It’s one thing to say you trust scientists, but what does that mean that you also don’t want them to play an active role in policy?

Continue Reading »

Oct

25

2022

At a recent talk, during the Q&A an audience member asked me what I thought the consequences would be of the “idiocracy” we seem to be heading toward. I challenged the premise, that people in general are becoming less intelligent. I know it may superficially seem like this, but that has more to do with media savvy, echochambers, tribalism, and radicalization, not any demonstrable decline in raw intelligence.

At a recent talk, during the Q&A an audience member asked me what I thought the consequences would be of the “idiocracy” we seem to be heading toward. I challenged the premise, that people in general are becoming less intelligent. I know it may superficially seem like this, but that has more to do with media savvy, echochambers, tribalism, and radicalization, not any demonstrable decline in raw intelligence.

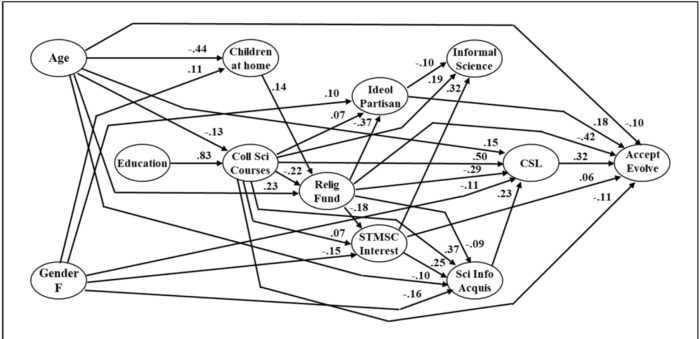

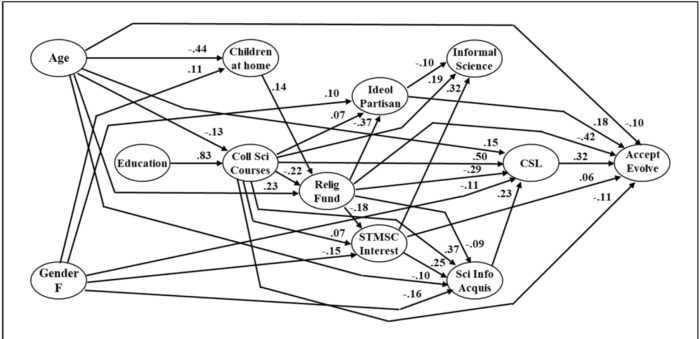

In fact, I pointed out, in the last century there has been a consistent increase in IQ testing ability, by about 3 IQ points per decade (called the Flynn Effect). There is still debate about what this means, and it is important to point out that IQ testing does not equal “intelligence” which is multifaceted. But whatever standard IQ tests are measuring, performance is generally improving over time. Another measure, that of civic scientific literacy (in a longstanding series of studies by Jon Miller), increased from 1988 t0 2008 from 9% to 29%. It has since plateaued at that level.

There is no consensus as to why this is so, but I have some thoughts based on the literature. Technology is exposing people to more information, and this has only been increasing further with the advent of computers, the internet, and even social media. Regardless of any negative effects, people seem to know more stuff, and have improved problem-solving skills. Our brains are busier, they are exposed to more ideas and facts, we interact with a greater number of different people and opinions, and we have to interface with technology and information more. The workforce is shifting from manual labor to more intellectual labor. Even just going through your normal day likely involves interacting with technology that would have befuddled older generations.

Continue Reading »

Oct

01

2021

There is pretty broad agreement that the pandemic was a net negative for learning among children. Schools are an obvious breeding ground for viruses, with hundreds or thousands of students crammed into the same building, moving to different groups in different classes, and with teachers being systematically exposed to many different students while they spray them with their possibly virus-laden droplets. Wearing masks, social distancing, and using plexiglass barriers reduces the spread, but not enough if we are in the middle of a pandemic surge. Only vaccines will make schools truly safe.

There is pretty broad agreement that the pandemic was a net negative for learning among children. Schools are an obvious breeding ground for viruses, with hundreds or thousands of students crammed into the same building, moving to different groups in different classes, and with teachers being systematically exposed to many different students while they spray them with their possibly virus-laden droplets. Wearing masks, social distancing, and using plexiglass barriers reduces the spread, but not enough if we are in the middle of a pandemic surge. Only vaccines will make schools truly safe.

So it was reasonable, especially in the early days of the pandemic, to convert schooling to online classes until the pandemic was under control. The problem was – most schools were simply not ready for this transition. The worst problem were those student who did not have access to a computer and the internet from home. The pandemic helped expose and exacerbate the digital divide. But even for students with good access, the experience was generally not good. Many teachers were not prepared to adapt their classes for online learning. Many parents did not have ability to stay at home with their kids to monitor them. And many children were simply bored and not learning.

This is a classic infrastructure problem. Many technologies do not function well in a vacuum. You can’t have cars without roads, traffic control, licensing, safety regulations, and fueling stations. Mass online learning also requires significant infrastructure that we simply didn’t have.

Continue Reading »

Aug

26

2021

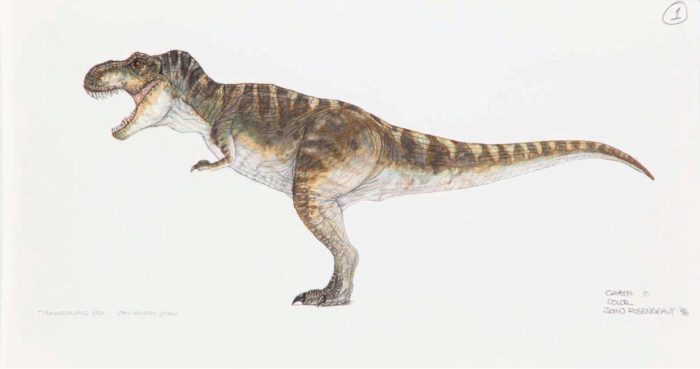

The idea that all life on Earth is related through a nested hierarchy of branching evolution, occurring over billions of years through entirely natural processes, is one of the biggest ideas ever to emerge from human science. It did not just emerge whole cloth from the brain of Charles Darwin, it had been percolating in the scientific community for decades. Darwin, however, put it all together in one long compelling argument. Alfred Wallace independently came up with essentially the same conclusion, although did not develop it as far as Darwin.

The idea that all life on Earth is related through a nested hierarchy of branching evolution, occurring over billions of years through entirely natural processes, is one of the biggest ideas ever to emerge from human science. It did not just emerge whole cloth from the brain of Charles Darwin, it had been percolating in the scientific community for decades. Darwin, however, put it all together in one long compelling argument. Alfred Wallace independently came up with essentially the same conclusion, although did not develop it as far as Darwin.

On the Origin of Species was published in 1859, and it quickly won over the scientific community, with natural selection acting on variation becoming the dominant working hypothesis. But that, of course, was not the end of the story, only the beginning. If Darwin’s ideas were wrong, they would have slowly withered from lack of confirming evidence. But they were largely correct, even insightful. The last 162 years of research and observation have confirmed to an extraordinary degree the core ideas that life is related through branching connections, and that natural selection is a primary driving force of evolution. The theory has also evolved quite a bit, and is now a mature and complex scientific discipline sitting on top of mountains of evidence, including fossils, genetics, comparative anatomy, developmental biology, and direct observation. The basic fact of evolution could have been falsified thousands of times over, but it has survived every time – because it is essentially true.

Acceptance of the basic tenets of evolutionary theory, therefore, is a good litmus test for any modern society. Of what, exactly, is another question, but certainly something is going wrong if the population does not accept this overwhelming scientific consensus. The US ranks second from the bottom (only Turkey is worse) in terms of accepting evolutionary theory. Researchers have been tracking the statistics for decades, and now some of the lead researchers in this field have published data from 1985 to 2020 (sorry it’s behind a paywall). There are some interesting details to pull from the numbers.

Continue Reading »

Sep

22

2020

The issue of genetically modified organisms is interesting from a science communication perspective because it is the one controversy that apparently most follows the old knowledge deficit paradigm. The question is – why do people reject science and accept pseudoscience. The knowledge deficit paradigm states that they reject science in proportion to their lack of knowledge about science, which should therefore be fixable through straight science education. Unfortunately, most pseudoscience and science denial does not follow this paradigm, and are due to other factors such as lack of critical thinking, ideology, tribalism, and conspiracy thinking. But opposition to GMOs does appear to largely result from a knowledge deficit.

The issue of genetically modified organisms is interesting from a science communication perspective because it is the one controversy that apparently most follows the old knowledge deficit paradigm. The question is – why do people reject science and accept pseudoscience. The knowledge deficit paradigm states that they reject science in proportion to their lack of knowledge about science, which should therefore be fixable through straight science education. Unfortunately, most pseudoscience and science denial does not follow this paradigm, and are due to other factors such as lack of critical thinking, ideology, tribalism, and conspiracy thinking. But opposition to GMOs does appear to largely result from a knowledge deficit.

A 2019 study, in fact, found that as opposition to GM technology increased, scientific knowledge about genetics and GMOs decreased, but self-assessment increased. GMO opponents think they know the most, but in fact they know the least. Other studies show that consumers have generally low scientific knowledge about GMOs. There is also evidence that fixing the knowledge deficit, for some people, can reduce their opposition to GMOs (at least temporarily). We clearly need more research, and also different people oppose GMOs for different reasons, but at least there is a huge knowledge deficit here and reducing it may help.

So in that spirit, let me reduce the general knowledge deficit about GMOs. I have been tackling anti-GMO myths for years, but the same myths keep cropping up (pun intended) in any discussion about GMOs, so there is still a lot of work to do. To briefly review – no farmer has been sued for accidental contamination, farmers don’t generally save seeds anyway, there are patents on non-GMO hybrid seeds, GMOs have been shown to be perfectly safe, GMOs did not increase farmer suicide in India, and use of GMOs generally decreases land use and pesticide use.

Continue Reading »

May

29

2020

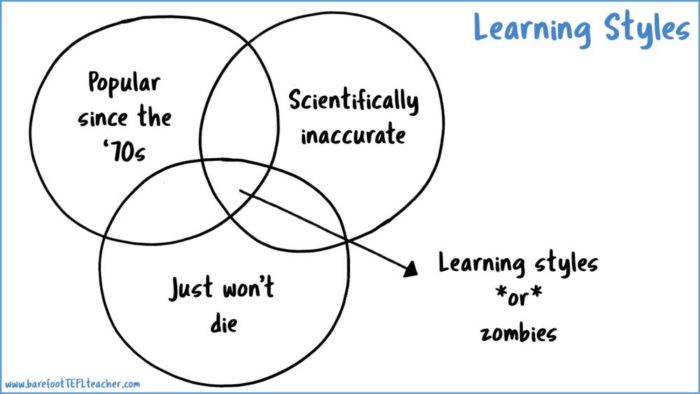

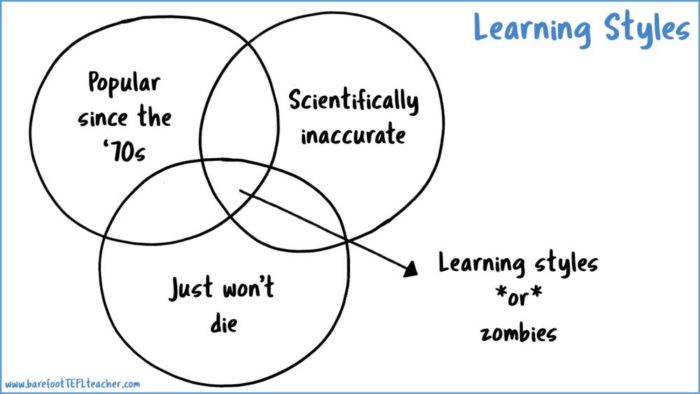

I have written previously about the fact that the scientific evidence does not support the notion that different people have different inherent learning styles. Despite this fact, the concept remains popular, not only in popular culture but among educators. For fun a took the learning style self test at educationplanner.org. It was complete nonsense. I felt my answer to all the forced-choice questions was “it depends.” In the end I scored 35% visual, 35% auditory, and 30% kinesthetic, from which the site concluded I was a visual-auditory learner.

about the fact that the scientific evidence does not support the notion that different people have different inherent learning styles. Despite this fact, the concept remains popular, not only in popular culture but among educators. For fun a took the learning style self test at educationplanner.org. It was complete nonsense. I felt my answer to all the forced-choice questions was “it depends.” In the end I scored 35% visual, 35% auditory, and 30% kinesthetic, from which the site concluded I was a visual-auditory learner.

Clearly we need to do a better job of getting the word out there – forget learning styles, it’s a dead end. The Yale Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning has done a nice job of summarizing why learning styles is a myth, and makes a strong case for why the concept is counterproductive.

The idea is that individual people learn better if the material is presented in a style, format, or context that fits best with their preferences. The idea is appealing because, first, everyone likes to think about themselves and have something to identify with. But also it gives educators the feeling that they can get an edge by applying a simple scheme to their teaching. I also frequently find it is a convenient excuse for lack of engagement with material.

There are countless schemes for separating the world into a limited number of learning styles. Perhaps the most popular is visual, auditory, vs kinesthetic. But there are many, and the Yale site lists the most popular. They include things such as globalists vs. analysts, assimilators vs. accommodators, imaginative vs. analytic learners, non-committers vs. plungers. If you think this is all sounding like an exercise in false dichotomies, I agree.

Regardless of why people find the notion appealing, or which system you prefer, the bottom line is that the basic concept of learning styles is simply not supported by scientific evidence.

Continue Reading »

Apr

16

2020

This should come as no surprise to any parent – children appear to prefer books that are loaded with causal information, meaning they address the questions of why, not just what. That children have a preference for causal information has already been established in the lab, but the new study claims to be the first to show this effect outside the lab in a more real-world setting.

This should come as no surprise to any parent – children appear to prefer books that are loaded with causal information, meaning they address the questions of why, not just what. That children have a preference for causal information has already been established in the lab, but the new study claims to be the first to show this effect outside the lab in a more real-world setting.

The study itself adds only a small bit of information, but is useful as far as it goes. The researchers had adult volunteers read two books to 48 children. The books were carefully matched in every way, except one book gave information about animals, while the other book also gave explanations for why animals had the traits and behaviors that they do. The children seemed to engage equally with both books, but afterwards expressed a clear preference for the book rich with causal information.

This is a reasonable confirmation of the laboratory-based research, but really doesn’t go that far. What we would like to know is if this stated preference predicts anything concrete. Are children more likely to read books with causal information, to read them longer, to absorb and retain more information, etc.? Does that affect their academic performance later in life? It makes sense that it would, but we need evidence to be sure.

We do know that reading aloud to young children is associated with better literacy outcomes. Simply having more books in the home is linked to better academic achievement (although this kind of data is rife with confounding factors, like socioeconomic status). Early academic skills, like reading, predict later academic success. Therefore anything that increases children’s motivation and enjoyment of reading is likely to have a positive effect. The hope is that information like this will allow for better targeting of books to children to engage their reading.

Continue Reading »

Apr

09

2020

While we are all shuttering at home, especially as the weeks drag on, many people are looking for some constructive things to do. Of course some of use can work from home, others have essential jobs and still have to go to work, but even then we are spending the rest of the time at home rather than going out. This has been a boon to streaming services, but also has changed perceptions about certain online activities, including telehealth, telemental health, online conferences, and online learning. Since we are basically forced to do this, some who were resistant to such things are learning that it’s not so bad. I do wonder how long this effect will last. Will this be a short-lived phase and we quickly revert to our past attitudes and standards, or will this permanently change the world? We’ll know in a few years.

While we are all shuttering at home, especially as the weeks drag on, many people are looking for some constructive things to do. Of course some of use can work from home, others have essential jobs and still have to go to work, but even then we are spending the rest of the time at home rather than going out. This has been a boon to streaming services, but also has changed perceptions about certain online activities, including telehealth, telemental health, online conferences, and online learning. Since we are basically forced to do this, some who were resistant to such things are learning that it’s not so bad. I do wonder how long this effect will last. Will this be a short-lived phase and we quickly revert to our past attitudes and standards, or will this permanently change the world? We’ll know in a few years.

Meanwhile, it’s good to know empirically if online learning, for example, is as effective as in person learning. This has already been the subject of many studies, and a recent study adds to the list. A 2010 meta-analysis of such research found that online learning was superior to traditional in person learning in terms of outcomes. However, these conclusions were criticized because the studies focused on well-prepared college students and may not generalize to the underprivileged or the general population. Overall the research shows that online learning is at least equivalent to in person learning, and may be superior in some cases.

The recent study is in line with this general trend in the research. This is what they did:

The experiment involved 325 second-year engineering students from resource-constrained universities. Students took two courses hosted by the national Open Education platform. Before the start of the course, they were randomly divided into three groups. The first group studied in person with the instructor at their university, the second group watched online lectures and attended in-person discussion sections (i.e., a blended modality), and the third group took the entire course online and communicated with instructors at the course’s forum.

They found that all three groups had the same learning as measured by testing. However, the online group had slightly higher grades on assignments, but slightly lower overall satisfaction. The lower satisfaction was related to unfamiliarity with online learning and some difficulty with self-time management. This suggests that online students need some structure and support.

Continue Reading »

There is an ongoing culture war, and not just in the US, over the content of childhood education, both public and private. This seems to be flaring up recently, but is never truly gone. Republicans in the US have recently escalated this war by banning over 500 books in several states (mostly Florida) because they contain “inappropriate” content. There are a few issues worth exploring here.

There is an ongoing culture war, and not just in the US, over the content of childhood education, both public and private. This seems to be flaring up recently, but is never truly gone. Republicans in the US have recently escalated this war by banning over 500 books in several states (mostly Florida) because they contain “inappropriate” content. There are a few issues worth exploring here.

Researchers recently published

Researchers recently published  A

A  At a recent talk, during the Q&A an audience member asked me what I thought the consequences would be of the “idiocracy” we seem to be heading toward. I challenged the premise, that people in general are becoming less intelligent. I know it may superficially seem like this, but that has more to do with media savvy, echochambers, tribalism, and radicalization, not any demonstrable decline in raw intelligence.

At a recent talk, during the Q&A an audience member asked me what I thought the consequences would be of the “idiocracy” we seem to be heading toward. I challenged the premise, that people in general are becoming less intelligent. I know it may superficially seem like this, but that has more to do with media savvy, echochambers, tribalism, and radicalization, not any demonstrable decline in raw intelligence. There is pretty broad agreement that the pandemic was a net negative for learning among children. Schools are an obvious breeding ground for viruses, with hundreds or thousands of students crammed into the same building, moving to different groups in different classes, and with teachers being systematically exposed to many different students while they spray them with their possibly virus-laden droplets. Wearing masks, social distancing, and using plexiglass barriers reduces the spread, but not enough if we are in the middle of a pandemic surge. Only vaccines will make schools truly safe.

There is pretty broad agreement that the pandemic was a net negative for learning among children. Schools are an obvious breeding ground for viruses, with hundreds or thousands of students crammed into the same building, moving to different groups in different classes, and with teachers being systematically exposed to many different students while they spray them with their possibly virus-laden droplets. Wearing masks, social distancing, and using plexiglass barriers reduces the spread, but not enough if we are in the middle of a pandemic surge. Only vaccines will make schools truly safe. The idea that all life on Earth is related through a nested hierarchy of branching evolution, occurring over billions of years through entirely natural processes, is one of the biggest ideas ever to emerge from human science. It did not just emerge whole cloth from the brain of Charles Darwin, it had been percolating in the scientific community for decades. Darwin, however, put it all together in one long compelling argument. Alfred Wallace independently came up with essentially the same conclusion, although did not develop it as far as Darwin.

The idea that all life on Earth is related through a nested hierarchy of branching evolution, occurring over billions of years through entirely natural processes, is one of the biggest ideas ever to emerge from human science. It did not just emerge whole cloth from the brain of Charles Darwin, it had been percolating in the scientific community for decades. Darwin, however, put it all together in one long compelling argument. Alfred Wallace independently came up with essentially the same conclusion, although did not develop it as far as Darwin. The issue of genetically modified organisms is interesting from a science communication perspective because it is the one controversy that apparently most follows the old knowledge deficit paradigm. The question is – why do people reject science and accept pseudoscience. The knowledge deficit paradigm states that they reject science in proportion to their lack of knowledge about science, which should therefore be fixable through straight science education. Unfortunately, most pseudoscience and science denial does not follow this paradigm, and are due to other factors such as lack of critical thinking, ideology, tribalism, and conspiracy thinking. But opposition to GMOs does appear to largely result from a knowledge deficit.

The issue of genetically modified organisms is interesting from a science communication perspective because it is the one controversy that apparently most follows the old knowledge deficit paradigm. The question is – why do people reject science and accept pseudoscience. The knowledge deficit paradigm states that they reject science in proportion to their lack of knowledge about science, which should therefore be fixable through straight science education. Unfortunately, most pseudoscience and science denial does not follow this paradigm, and are due to other factors such as lack of critical thinking, ideology, tribalism, and conspiracy thinking. But opposition to GMOs does appear to largely result from a knowledge deficit.

This should come as no surprise to any parent –

This should come as no surprise to any parent –  While we are all shuttering at home, especially as the weeks drag on, many people are looking for some constructive things to do. Of course some of use can work from home, others have essential jobs and still have to go to work, but even then we are spending the rest of the time at home rather than going out. This has been a boon to streaming services, but also has changed perceptions about certain online activities, including telehealth, telemental health, online conferences, and online learning. Since we are basically forced to do this, some who were resistant to such things are learning that it’s not so bad. I do wonder how long this effect will last. Will this be a short-lived phase and we quickly revert to our past attitudes and standards, or will this permanently change the world? We’ll know in a few years.

While we are all shuttering at home, especially as the weeks drag on, many people are looking for some constructive things to do. Of course some of use can work from home, others have essential jobs and still have to go to work, but even then we are spending the rest of the time at home rather than going out. This has been a boon to streaming services, but also has changed perceptions about certain online activities, including telehealth, telemental health, online conferences, and online learning. Since we are basically forced to do this, some who were resistant to such things are learning that it’s not so bad. I do wonder how long this effect will last. Will this be a short-lived phase and we quickly revert to our past attitudes and standards, or will this permanently change the world? We’ll know in a few years.