Our ability to detect, amplify, and sequence tiny amount of DNA has lead to a scientific revolution. We can now take a small sample of water from a lake, and by analyzing the environmental DNA in that water determine all of the things that live in the lake. This is an amazingly powerful tool. My favorite application of this technique was to demonstrate the absence of DNA in Loch Ness from any giant reptile or aquatic dinosaur. So-called eDNA is perhaps the most powerful evidence of a negative, the absence of a creature in an environment – you can’t hide your eDNA.

Our ability to detect, amplify, and sequence tiny amount of DNA has lead to a scientific revolution. We can now take a small sample of water from a lake, and by analyzing the environmental DNA in that water determine all of the things that live in the lake. This is an amazingly powerful tool. My favorite application of this technique was to demonstrate the absence of DNA in Loch Ness from any giant reptile or aquatic dinosaur. So-called eDNA is perhaps the most powerful evidence of a negative, the absence of a creature in an environment – you can’t hide your eDNA.

The ultimate limiting factor on eDNA is how long such DNA will survive. DNA has a half-life, it spontaneously degrades and sheds information, until it is no longer useful for sequencing. Previously scientists extracted DNA from ice cores in Greenland, and were able to sequence DNA up to 800,000 years old. The oldest DNA ever recovered was probably 1.1-1.2 million years old. Based on this scientists estimated that the ultimate lifespan of usable DNA was about 1 million years. This put the final nail in the coffin of any dreams of a Jurassic park. Non-avian dinosaurs died out 65 million years ago, so none of their DNA should still be left on Earth (the closest we can get is related DNA in birds). But no T. rex DNA in amber.

According to a new assay in the most norther region of Greenland, however, we have to push back the estimate of how long DNA can survive to at least 2 million years. That is a significant increase (but still a long way from T. rex). The site is Kap København Formation located in Peary Land in north Greenland. This is now a barren frozen desert. There are also very few macrofossils here, mostly from a boreal forest and insects, with the only vertebrate being a hare’s tooth. Conditions there are apparently not conducive to fossilization. We do know that 2 million years ago Greenland was much warmer, about 10 degrees C warmer than present. So there is no reason it should not have been teeming with life.

The new analysis of eDNA finds that, in fact, it was. They found DNA from hares, but also other rodents, reindeer, geese, and mastodons. They also found DNA from poplars, birch trees, and thuja trees (a type of coniferous tree), as well as a rich assortment of bushes, herbs, and other flora. Basically this was a mixed forest with a rich ecosystem. In addition they found marine species including horseshoe crab and green algae, confirming the warmer climate.

This ancient eDNA gives us a much more complete picture of the ecosystem than was provided by macrofossils alone. But perhaps more importantly – it demonstrates that eDNA can survive for up to two million years, doubling the previous estimate. The researchers speculate that minerals in the soil bound to the DNA and stabilized it, slowing its degradation. DNA is negatively charged. This property is used to separate out chunks of DNA in a sample by size. You apply a magnetic field which attracts the DNA pieces, which move through a gel at a range proportional to their size. In this case the negatively charged DNA bound to positively charged minerals in the soil. I guess this is the DNA version of fossilization.

The question is – in such environments where DNA is stabilized by binding to minerals, how much is the degradation process slowed down, and therefore how long can DNA survive? DNA breaks down due to “microbial enzymatic activity, mechanical shearing and spontaneous chemical reactions such as hydrolysis and oxidation.” DNA breaks down faster with warmer temperature, so the fact that this DNA remained frozen for so long is crucial. But freezing alone was not enough, which is why scientists think that binding to minerals also played a role.

They measured the “thermal age” of the DNA – if the DNA were at a constant temperature of 10 degrees C how long would it have taken to degrade to its current state – at 2.7 thousand years, 741 times less than its actual age of 2 million years. Therefore it degraded 741 times slower then exposed DNA at 10 degrees C. The average temperature at the site is -17 degrees C. They further found that the DNA was bound mostly to clay minerals, and specifically smectite (and to a lesser degree, quartz).

Perhaps this is the limit of DNA survival – although we thought the previous record of 1.1-1.2 million years was the limit. It is possible there may be environmental conditions elsewhere in the world that could slow DNA degradation even further. Slow DNA degradation by a factor of 30 or so beyond the Kap København Formation and we are getting into the time of dinosaurs. This is probably unlikely. Constant freezing temperatures are required, in addition to geological stability and optimal soil conditions. But I don’t think we can say now that it is impossible, just highly unlikely. I did not see any estimate in the study about the ultimate upper limit of DNA lifespan, but I suspect we will see such analyses based on this latest information.

The best evidence, however, will come from simply looking in new locations for eDNA, especially those that likely have the optimal conditions for maximal DNA longevity. But for now, being able to reconstruct ecosystems from 2 million years ago is still pretty cool.

Evolution deniers (I know there is a spectrum, but generally speaking) are terrible scientists and logicians. The obvious reason is because they are committing the primary mortal sin of pseudoscience – working backwards from a desired conclusion rather than following evidence and logic wherever it leads. They therefore clasp onto arguments that are fatally flawed because they feel they can use them to support their position. One could literally write a book using bad creationist arguments to demonstrate every type of poor reasoning and pseudoscience (I should know).

Evolution deniers (I know there is a spectrum, but generally speaking) are terrible scientists and logicians. The obvious reason is because they are committing the primary mortal sin of pseudoscience – working backwards from a desired conclusion rather than following evidence and logic wherever it leads. They therefore clasp onto arguments that are fatally flawed because they feel they can use them to support their position. One could literally write a book using bad creationist arguments to demonstrate every type of poor reasoning and pseudoscience (I should know).

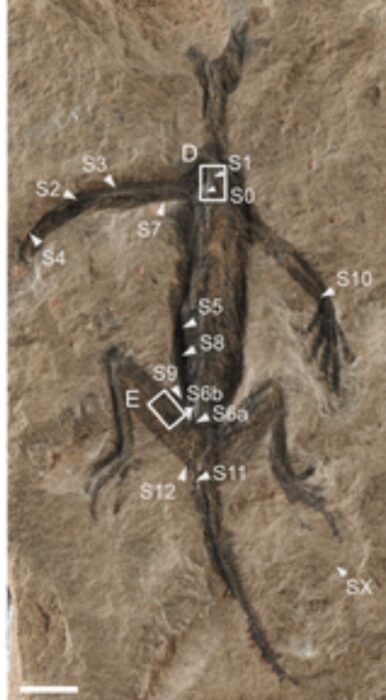

In 1931 a fossil lizard was recovered from the Italian Alps, believed to be a 280 million year old specimen. The fossil was also rare in that it appeared to have some preserved soft tissue. It was given the species designation Tridentinosaurus antiquus and was thought to be part of the Protorosauria group.

In 1931 a fossil lizard was recovered from the Italian Alps, believed to be a 280 million year old specimen. The fossil was also rare in that it appeared to have some preserved soft tissue. It was given the species designation Tridentinosaurus antiquus and was thought to be part of the Protorosauria group. Have you heard of Cope’s Rule or Foster’s Rule?

Have you heard of Cope’s Rule or Foster’s Rule?  The largest and heaviest animal to ever live on the Earth, as far as we know, is the blue whale, which is extant today. The blue whale is larger than any dinosaur, even the giant sauropods. The average weight of a blue whale is 160 tons, with

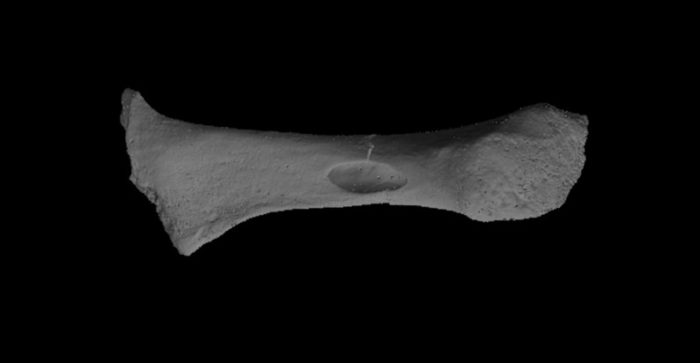

The largest and heaviest animal to ever live on the Earth, as far as we know, is the blue whale, which is extant today. The blue whale is larger than any dinosaur, even the giant sauropods. The average weight of a blue whale is 160 tons, with Researchers report a 3D scan of the

Researchers report a 3D scan of the  Our ability to detect, amplify, and sequence tiny amount of DNA has lead to a scientific revolution. We can now take a small sample of water from a lake, and by analyzing the environmental DNA in that water determine all of the things that live in the lake. This is an amazingly powerful tool. My favorite application of this technique was to demonstrate

Our ability to detect, amplify, and sequence tiny amount of DNA has lead to a scientific revolution. We can now take a small sample of water from a lake, and by analyzing the environmental DNA in that water determine all of the things that live in the lake. This is an amazingly powerful tool. My favorite application of this technique was to demonstrate  Yesterday

Yesterday

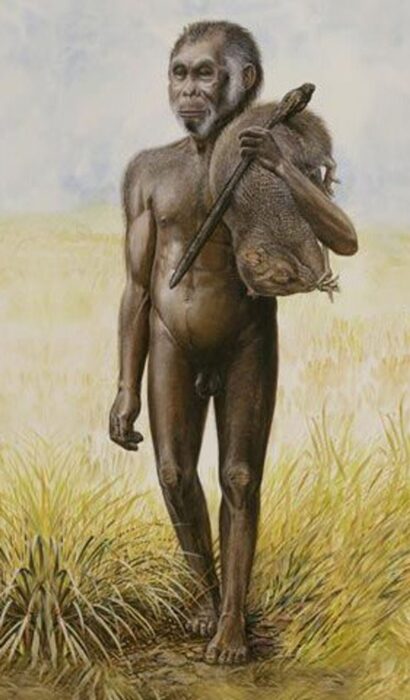

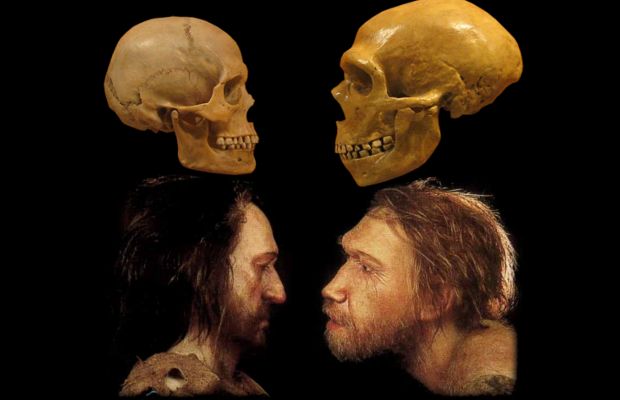

Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) is the closest evolutionary cousin to modern humans (Homo sapiens). In fact they are so close there has been some debate about whether or not they are truly a separate species from humans or if they are a subspecies (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis), but it seems the consensus has moved toward the former recently. They are not our ancestors – humans did not evolve from Neanderthals (anymore than we evolved from modern Chimps). Rather, we share a common ancestor with Neanderthals, about 700,000 years ago.

Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) is the closest evolutionary cousin to modern humans (Homo sapiens). In fact they are so close there has been some debate about whether or not they are truly a separate species from humans or if they are a subspecies (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis), but it seems the consensus has moved toward the former recently. They are not our ancestors – humans did not evolve from Neanderthals (anymore than we evolved from modern Chimps). Rather, we share a common ancestor with Neanderthals, about 700,000 years ago. The arms of a T-rex are iconic for several reasons. First, they are comically small. T. rex itself is a superstar of the dinosaur world – perhaps the most famous extinct predator. Its jaws are massive and terrifying. Yet just behind those killer teeth there are these tiny arms that seem out of proportion, and scientists struggle to figure out what they are for and why they are so small. In fact, when the first T. rex skeleton was discovered

The arms of a T-rex are iconic for several reasons. First, they are comically small. T. rex itself is a superstar of the dinosaur world – perhaps the most famous extinct predator. Its jaws are massive and terrifying. Yet just behind those killer teeth there are these tiny arms that seem out of proportion, and scientists struggle to figure out what they are for and why they are so small. In fact, when the first T. rex skeleton was discovered