Apr

30

2020

Perhaps the most persistent and annoying question promoters of science-based medicine get is, “What’s the harm?” The implication is we should just let people use their Reiki or magic potions if it makes them feel like they are doing something, as long as the treatment is not directly physically harmful. As you can see, I have been addressing it for years, including the fact that I will have to address it for years. There is also well documented real physical harm from many unscientific treatments, but even without that the harm is substantial.

Perhaps the most persistent and annoying question promoters of science-based medicine get is, “What’s the harm?” The implication is we should just let people use their Reiki or magic potions if it makes them feel like they are doing something, as long as the treatment is not directly physically harmful. As you can see, I have been addressing it for years, including the fact that I will have to address it for years. There is also well documented real physical harm from many unscientific treatments, but even without that the harm is substantial.

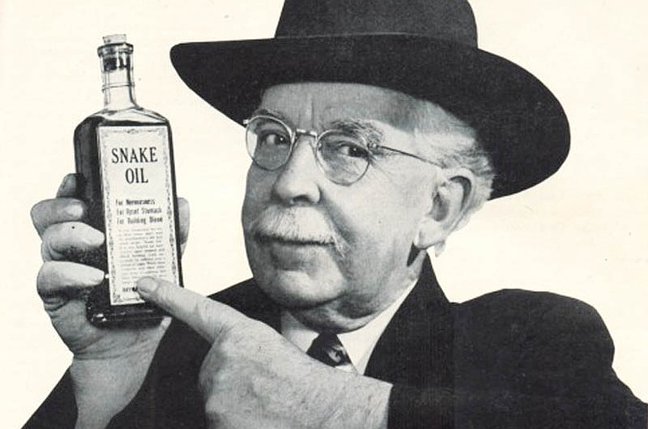

As a physician I have seen first hand much of the harm that can result – such as wasted time and effort, expenditure of limited resources, the psychological harm of false hope, and delaying effective treatment. But I have also warned about the harm to our scientific, medical, and societal infrastructures. This is difficult to quantify, but what is happening is that we are allowing to thrive a multi-billion dollar industry funneling money to charlatans, quacks, con-artists, pseudoscientists, those who discount science, and conspiracy theorists. Do you think they are just taking their money and staying quiet? No. They are using some of those billions to lobby for laws to water down public protections, weaken regulations, and funnel taxpayer money into promoting their snake oil.

This multi-billion dollar industry is also engaged in a massive advertising campaign, which amounts to a disinformation campaign, for their “brand”, which is alternative, complementary, integrative, functional, whatever medicine. They have spent decades misinforming the public about the relative significance of various health risks and benefits, the nature of disease, and the trustworthiness of scientists and experts. They have been a major component in the war on expertise, and to a large extent they are winning.

Continue Reading »

Apr

28

2020

Several alleged UFO videos have been circulating for the last few years, and now the Pentagon has officially released them, in order to dampen public speculation about their authenticity. There is now no question that the videos are genuine Navy videos of unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP). But of course, the core questions remains – what are they?

Several alleged UFO videos have been circulating for the last few years, and now the Pentagon has officially released them, in order to dampen public speculation about their authenticity. There is now no question that the videos are genuine Navy videos of unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP). But of course, the core questions remains – what are they?

The temptation, of course, is to leap from “unidentified” or unknown to “alien.” As I have discussed before, this also happens with astronomical observations, although professional astronomers tend to be more cautious. Every time we encounter a previously unknown astronomical phenomenon (starting, famously, with pulsars that were originally nicknamed LGMs for “little green men”) someone speculates if we can be seeing an alien artifact. So far the answer has been no.

The Pentagon has a program, previously secret but now acknowledged, to seek out, document, and examine UAP. The concern was not alien visitors, but foreign technology. Do the Russians have spy drones we might want to know about? Or perhaps we can detect testing of new weapons. Out of this program, these three released videos emerged. So let’s step back and ask the question everyone wants to ask – what is the probability that one or more of these videos represent alien technology visiting the Earth? I would argue that the answer is – extremely low.

Part of the reason for this answer is that rare things are rare. So far we have no confirmation that aliens are on or near the Earth. We have no confirmation that alien technological civilizations exist within feasible travel range to the Earth. They have not made their presence known, and there isn’t a single piece of objective or undeniable evidence. So the chance that some unknown phenomenon represents a specific, new, and unlikely phenomenon is inherently unlikely. This factor is often neglected, especially by believers. What are the odds that that indistinct blob verifies your specific beliefs?

Continue Reading »

Apr

27

2020

SARS-Cov2 is a challenging little bugger, but in my assessment no match for human science and ingenuity. There are already 1,650 listed scientific articles on COVID-19 and 450 ongoing clinical trials. In short, we are scienceing the shit out of this pandemic and we will get through it. But as I have argued previously, perhaps a bigger threat than the virus itself is human psychology. Crises bring out the best and worst in people, and we are seeing both in spades. Also, a crisis exposes the weaknesses in institutions, and they are being highlighted as well.

That’s why, in medicine, we have something called M and M – morbidity and mortality rounds. The goal of these rounds is to review all negative clinical outcomes in whatever setting is being covered and try to figure out what went wrong. But, importantly, such conferences are not about assigning blame, recrimination, or discipline. It is about improving the system. Was a particular negative outcome unavoidable? Was it precipitated by a personal failure, or rather a systemic failure. And if not a failure per se, is there some systematic change we can put in place to minimize these negative outcomes in the future? Should this be handled by education, by some additional checklist or process, or by reconfiguring the workforce?

For some crises, like the pandemic (or a war, for example), we can’t wait until it’s all over to look back and analyze the systemic shortcomings (although we should do this also, to prepare for the next one). We need ongoing analysis and adjustment. That is what a group of psychologists have done, with respect to common psychological pitfalls and how they might affect our individual response to the pandemic. I like this review because it is square in the tradition of skeptical thinking – it identifies psychological pitfalls so that we can better understand ourselves, and proposes specific adjustments we can do to mitigate them. You can read the full article, but I want to highlight a few of particular interset.

Continue Reading »

Apr

24

2020

On this week’s SGU (which will go online tomorrow) I talked about the use of ultraviolet light as an anti-viral strategy. I wasn’t planning on also writing about it, but then the president decided to make some incredibly dubious comments about is, so I thought I would address it here. Here’s what he said:

On this week’s SGU (which will go online tomorrow) I talked about the use of ultraviolet light as an anti-viral strategy. I wasn’t planning on also writing about it, but then the president decided to make some incredibly dubious comments about is, so I thought I would address it here. Here’s what he said:

“So, supposing we hit the body with a tremendous – whether it’s ultraviolet or just very powerful light,” the president said, turning to Dr Deborah Birx, the White House coronavirus response co-ordinator, “and I think you said that hasn’t been checked but you’re going to test it.

“And then I said, supposing you brought the light inside of the body, which you can do either through the skin or in some other way. And I think you said you’re going to test that too. Sounds interesting,” the president continued.

He also made some ever sillier comments about injecting people with disinfectant – both comments commit the same error, confusing an external treatment for an internal one., and also suggesting that treatments meant for objects be used on people. So what is the deal with UV light as an antiseptic? The antiseptic effects of UV light have been known for a long time. In 1878, Arthur Downes and Thomas P. Blunt published the first paper describing this effect. Ultraviolet light has enough energy to cause tissue damage – that is why you get a sunburn if you get too much sun exposure.

UV light is electromagnetic radiation between visible light and X-rays on the spectrum, from 10-400 nm wavelength. These are higher energy waves than visible light, with enough energy to cause chemical reactions and damage DNA. UV light is further divided into biological relevant categories of UVA (400-315 nm), UVB (315-280 nm) and UVC (280-100 nm). The ozone layer filters out 97-99% of UV radiation from 315-200 nm, so the UVB and part of the UVC spectrum. Otherwise the suns rays would be much more harmful. On the Earth’s surface there is about 500 times the intensity of UVA than UVB, and almost no UVC. Biologically, UVA penetrates deeper into the skin and does cause long term aging effects. UVB affects the skin surface but causes sunburns and damage that can lead to skin cancer. UVC could cause extreme damage even with minutes of exposure (depending on the intensity).

Continue Reading »

Apr

23

2020

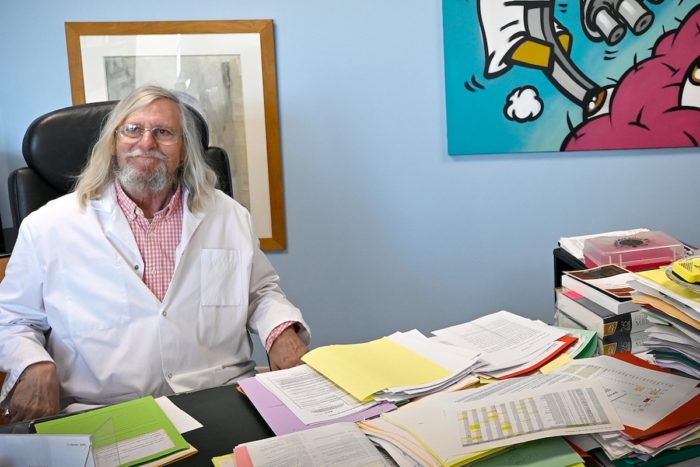

We have been tracking the story of the hype surrounding hydroxychloroquine over at Science-Based Medicine, but there is a brief follow up I wanted to comment on. The short version of the story so far is that one very bad French study claimed to show dramatic reduction in detected virus in those treated. This study, however, was not only preliminary, it was a horrible study, so much so that the results are uninterpretable. The big problem was that it did not count patients who became too sick or died. That is a classic way to make a treatment look better than it is. The author is also a climate change denier who initially mocked China for taking steps to mitigate Covid-19. He does not exactly have street cred within the scientific community.

We have been tracking the story of the hype surrounding hydroxychloroquine over at Science-Based Medicine, but there is a brief follow up I wanted to comment on. The short version of the story so far is that one very bad French study claimed to show dramatic reduction in detected virus in those treated. This study, however, was not only preliminary, it was a horrible study, so much so that the results are uninterpretable. The big problem was that it did not count patients who became too sick or died. That is a classic way to make a treatment look better than it is. The author is also a climate change denier who initially mocked China for taking steps to mitigate Covid-19. He does not exactly have street cred within the scientific community.

But that one horrible study from a sketchy researcher was enough to spark media hype, at least in certain circles, and capture the attention of a president apparently desperate to make this problem go away. Amid the fear of a pandemic, that was a toxic combination. The notion that hydroxychloroquine (with our without the antibiotic, azythromycin) might fight the SARS-Cov2 virus is not implausible. But most things in medicine that are “not implausible” don’t work out. We need high quality clinical science to ultimately tell.

The big question always is – what is the risk vs benefit? Hydroxychloroquine and Azythromycin both have the same potentially deadly side effect, prolonging the QT interval of the heart, which increases the risk for sudden cardiac death. This is a manageable side effect in the right setting, but is potentially serious. This is not a good drug or combination to be taking just on the chance it might help.

Continue Reading »

Apr

21

2020

Is our solar system similar to other solar systems? That’s actually a complex question with many layers. We know that there are different types of stars, varying mainly on their mass and age. We have a yellow sun, but a system around a red, orange, or blue sun is likely to be very different. We also know that at different relative locations in the galaxy the composition of the gas clouds out of which stellar systems form can be very different. One specific difference is known as “metallicity” – which refers to the amount of elements heavier than hydrogen or helium. Older stars were formed before a lot of heavier elements were made, so they have lower mellacity. This feature also varies within our galaxy, with higher metallicity closer to the center. And different galaxies have different mettalicity.

Is our solar system similar to other solar systems? That’s actually a complex question with many layers. We know that there are different types of stars, varying mainly on their mass and age. We have a yellow sun, but a system around a red, orange, or blue sun is likely to be very different. We also know that at different relative locations in the galaxy the composition of the gas clouds out of which stellar systems form can be very different. One specific difference is known as “metallicity” – which refers to the amount of elements heavier than hydrogen or helium. Older stars were formed before a lot of heavier elements were made, so they have lower mellacity. This feature also varies within our galaxy, with higher metallicity closer to the center. And different galaxies have different mettalicity.

But what should we expect from a stellar system with a yellow sun at a similar location in our own galaxy? If the known variables are the same, should we expect the compositions of elements to also be roughly the same? This gets to the deeper scientific question of how typical our system is. Can we assume that the rest of the universe is similar to our tiny little corner of it? To counteract the hubris of humanity in thinking that we are somehow special, scientists try to follow the principle to assume that we are ordinary. But is that assumption always correct?

How can we even answer this question for stars that are light-years away? The primary method that we use is spectral analysis (spectroscopy) – an awesomely powerful tool that allows us to identify specific elements and chemicals simply from analyzing the light we see from it. You can do a spectral analysis in a lab on a sample, or you can do it with telescopes on distant objects. The method is actually fairly simply. You use a prism to spread out the light into its color spectrum (like a rainbow). You can then analyze the emission lines or absorption lines which are like a signature.

Continue Reading »

Apr

20

2020

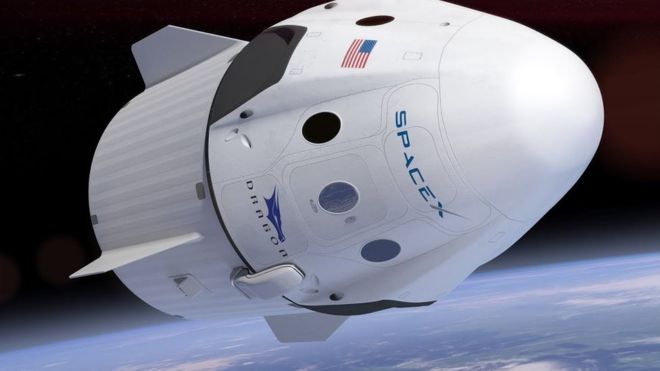

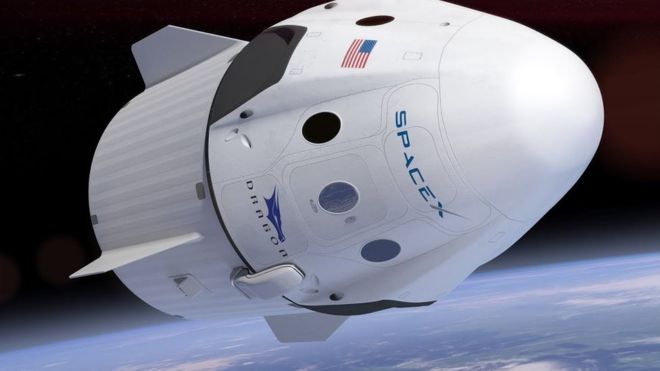

Amid the current crisis there is some good news and significant progress – America is returning to crewed spaceflight after a 9 year gap. Scheduled for May 27th is the first crewed mission of the Space X Dragon capsule, which will send two astronauts to the ISS, Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley. Technically this is the last test flight of the Crew Dragon capsule (the mission is called Demo-2). Last March the Demo-1 mission sent an uncrewed Dragon capsule to the ISS. The two astronauts will remain for an “extended” stay on the ISS, and then return in the capsule, splashing down in the Atlantic and recovered by a Space X recovery vessel.

Amid the current crisis there is some good news and significant progress – America is returning to crewed spaceflight after a 9 year gap. Scheduled for May 27th is the first crewed mission of the Space X Dragon capsule, which will send two astronauts to the ISS, Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley. Technically this is the last test flight of the Crew Dragon capsule (the mission is called Demo-2). Last March the Demo-1 mission sent an uncrewed Dragon capsule to the ISS. The two astronauts will remain for an “extended” stay on the ISS, and then return in the capsule, splashing down in the Atlantic and recovered by a Space X recovery vessel.

If successful this will mark the return of America’s ability to send astronauts into orbit. It will also mark the first time a commercial company has done so, and is a significant milestone in the commercialization of space flight. The launch will be done in cooperation with NASA, lifting off from Pad 39A, which is the same one that launched Apollo and the Space Shuttle. The capsule will also be lifted to the ISS by a Falcon 9 rocket, which is also made by Space X. This is the rocket that can land again vertically and be reused.

There has been some back and forth on whether or not the Crew Dragon capsules themselves can be reused. Initially Musk predicted that the capsule could be reused many times, reducing the cost of getting astronauts into space. Then in 2018 they quietly backed away from this goal. The reason is that after a salt-water landing, it is time consuming (a year) and expensive to service the capsule for reuse. In order for capsule reuse to be practical you need a dry landing, which was the original plan of Space X. Apparently that has proven technologically difficult, so Space X is settling for salt-water landings, which means no reuse. However, the Crew Dragon capsule can more easily be refurbished and reused for Cargo Dragon missions without astronauts. Therefore, they will be used for this purpose. Space X has reused multiple Cargo Dragon capsules multiple time.

Continue Reading »

Apr

17

2020

The World Health Organization (WHO) is one of those entities that are so essential if it didn’t exist it would need to be invented. But at the same time, it is a frustratingly flawed institution. Some of those flaws are being highlighted during the Covid-19 pandemic. But the WHO is not alone in this – Covid-19 is an extreme stress on the system, and it is revealing multiple weaknesses. The big lesson I hope at least a majority of people take from this entire episode is that we actually need continuity of competent government.

The World Health Organization (WHO) is one of those entities that are so essential if it didn’t exist it would need to be invented. But at the same time, it is a frustratingly flawed institution. Some of those flaws are being highlighted during the Covid-19 pandemic. But the WHO is not alone in this – Covid-19 is an extreme stress on the system, and it is revealing multiple weaknesses. The big lesson I hope at least a majority of people take from this entire episode is that we actually need continuity of competent government.

The WHO is essential for establishing international standards of medical care, and helping deliver modern medicine to the developing world. They are a critical source of information on epidemiology, and often the first source I go to when researching a medical topic. They have become a critical trust of medical, public health, and epidemiological expertise. They are also critical in dealing with things like pandemics. Here is their list of their primary goals, but in short:

Our goal is to ensure that a billion more people have universal health coverage, to protect a billion more people from health emergencies, and provide a further billion people with better health and well-being.

The WHO is a creature of the UN and came into existence in 1948 (just three years after the UN itself). They have 7,000 employees in offices in 150 countries. Ideally, an organization dedicated to health would be apolitical, nonpartisan, and heavily science-based. In a way the WHO represents the highest ideals of the UN – many nations getting together to cooperate for mutual benefit. But predictably it’s difficult to get so many different cultures and perspectives to collaborate seamlessly, and this has lead to what I consider some major problems with the WHO.

Continue Reading »

Apr

16

2020

This should come as no surprise to any parent – children appear to prefer books that are loaded with causal information, meaning they address the questions of why, not just what. That children have a preference for causal information has already been established in the lab, but the new study claims to be the first to show this effect outside the lab in a more real-world setting.

This should come as no surprise to any parent – children appear to prefer books that are loaded with causal information, meaning they address the questions of why, not just what. That children have a preference for causal information has already been established in the lab, but the new study claims to be the first to show this effect outside the lab in a more real-world setting.

The study itself adds only a small bit of information, but is useful as far as it goes. The researchers had adult volunteers read two books to 48 children. The books were carefully matched in every way, except one book gave information about animals, while the other book also gave explanations for why animals had the traits and behaviors that they do. The children seemed to engage equally with both books, but afterwards expressed a clear preference for the book rich with causal information.

This is a reasonable confirmation of the laboratory-based research, but really doesn’t go that far. What we would like to know is if this stated preference predicts anything concrete. Are children more likely to read books with causal information, to read them longer, to absorb and retain more information, etc.? Does that affect their academic performance later in life? It makes sense that it would, but we need evidence to be sure.

We do know that reading aloud to young children is associated with better literacy outcomes. Simply having more books in the home is linked to better academic achievement (although this kind of data is rife with confounding factors, like socioeconomic status). Early academic skills, like reading, predict later academic success. Therefore anything that increases children’s motivation and enjoyment of reading is likely to have a positive effect. The hope is that information like this will allow for better targeting of books to children to engage their reading.

Continue Reading »

Apr

13

2020

I have written quite a bit about the body part ownership illusion (sometimes called the “rubber hand illusion” because of the original study design). The idea is that the brain constructs all our sensations, perceptions, and experiences, including the sense that we own, occupy, and control our various body parts and our whole body. All it takes, apparently, is synchronization between seeing the “rubber hand” being touched and feeling your own hand being touched. Visual-tactile synchrony triggers the sensation of ownership. There is a robust replicated body of research supporting this conclusion. But particularly when people are the subject of research, no conclusion is beyond reconsideration.

I have written quite a bit about the body part ownership illusion (sometimes called the “rubber hand illusion” because of the original study design). The idea is that the brain constructs all our sensations, perceptions, and experiences, including the sense that we own, occupy, and control our various body parts and our whole body. All it takes, apparently, is synchronization between seeing the “rubber hand” being touched and feeling your own hand being touched. Visual-tactile synchrony triggers the sensation of ownership. There is a robust replicated body of research supporting this conclusion. But particularly when people are the subject of research, no conclusion is beyond reconsideration.

That is the core strength of science – it constantly questions and reexamines its own assumptions and conclusions. Psychological research especially needs to do so, because human behavior is horrifically complicated and we cannot directly see (well, not yet) what is happening in someone’s mind, so we have to infer what is happening from things like behavior. That inference is usually based on some construct – some idea about how people operate and how this will translate into their behavior in a psychological experiment.

For example, there is the now famous marshmallow test. In this robust series of experiments, children were offered a marshmallow (or some treat) and told they could eat it now, but if they wait a few minutes the researcher would be back with a second marshmallow and they could have two. The construct for these experiments is that children with more ability to defer gratification through executive function will be able to hold out for the second marshmallow. So in the end this is meant as an experimental measure of executive function. This conclusion was accepted for decades – until it was questioned. There is another possible interpretation of the results – at least some of the children who don’t hold out and go right for the initial treat may not trust that the researcher will be back with more. They will take the bird-in-the-hand. This is a rational response – especially if you have lived your life with adults who are less trustworthy and where basic resources may be limited. And in fact children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, with less trust and stability, generally do worse on the marshmallow test.

We may now be facing a similar reinterpretation of the body owernership illusion experiments, although at this point I don’t think it is going to turn out that way. A new paper, however, does point out a very important consideration that this and similar research must take into consideration – the role of demand characteristics. The idea itself is nothing new. In psychological experiments the study design must take into consideration the fact that subjects subconsciously try to figure out what the experimenter wants and then gives it to them. Any subtle cue that one response is more desired than another can affect the outcome. So the influence of demand characteristics must be carefully controlled for.

Continue Reading »

Perhaps the most persistent and annoying question promoters of science-based medicine get is, “What’s the harm?” The implication is we should just let people use their Reiki or magic potions if it makes them feel like they are doing something, as long as the treatment is not directly physically harmful. As you can see, I have been addressing it for years, including the fact that I will have to address it for years. There is also well documented real physical harm from many unscientific treatments, but even without that the harm is substantial.

Perhaps the most persistent and annoying question promoters of science-based medicine get is, “What’s the harm?” The implication is we should just let people use their Reiki or magic potions if it makes them feel like they are doing something, as long as the treatment is not directly physically harmful. As you can see, I have been addressing it for years, including the fact that I will have to address it for years. There is also well documented real physical harm from many unscientific treatments, but even without that the harm is substantial.

Several alleged UFO videos have been circulating for the last few years, and now the

Several alleged UFO videos have been circulating for the last few years, and now the

On this week’s SGU (which will go online tomorrow) I talked about the use of ultraviolet light as an anti-viral strategy. I wasn’t planning on also writing about it, but then the president decided to

On this week’s SGU (which will go online tomorrow) I talked about the use of ultraviolet light as an anti-viral strategy. I wasn’t planning on also writing about it, but then the president decided to  We have been

We have been  Amid the current crisis there is some good news and significant progress – America is returning to crewed spaceflight after a 9 year gap. Scheduled for May 27th is the

Amid the current crisis there is some good news and significant progress – America is returning to crewed spaceflight after a 9 year gap. Scheduled for May 27th is the The World Health Organization (WHO) is one of those entities that are so essential if it didn’t exist it would need to be invented. But at the same time, it is a frustratingly flawed institution. Some of those flaws are being highlighted during the Covid-19 pandemic. But the WHO is not alone in this – Covid-19 is an extreme stress on the system, and it is revealing multiple weaknesses. The big lesson I hope at least a majority of people take from this entire episode is that we actually need continuity of competent government.

The World Health Organization (WHO) is one of those entities that are so essential if it didn’t exist it would need to be invented. But at the same time, it is a frustratingly flawed institution. Some of those flaws are being highlighted during the Covid-19 pandemic. But the WHO is not alone in this – Covid-19 is an extreme stress on the system, and it is revealing multiple weaknesses. The big lesson I hope at least a majority of people take from this entire episode is that we actually need continuity of competent government. This should come as no surprise to any parent –

This should come as no surprise to any parent –  I have

I have