May

16

2024

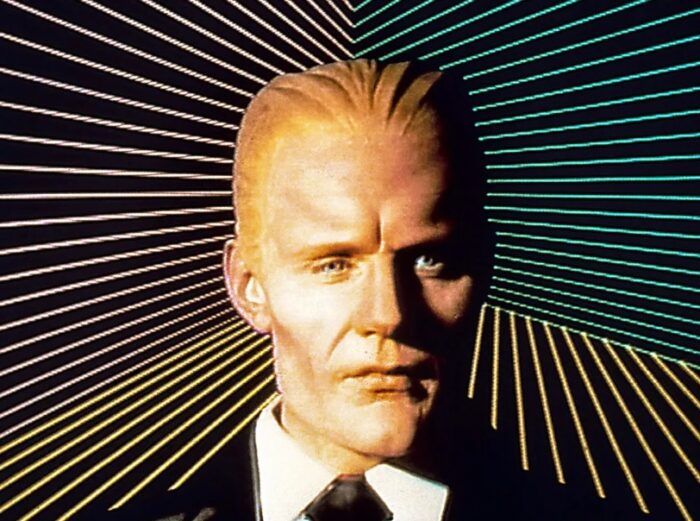

In the awesome show, Black Mirror, one episode features a young woman who lost her husband. In her grief she turns to a company that promises to give her at least a partial experience of her husband. They sift through every picture, video, comment, and other online trace of the person and construct from that a virtual avatar. At first the avatar just texts with the wife, which then progresses to phone calls, and then finally to a full robotic avatar indistinguishable from the lost husband. Except – it is not really indistinguishable. It’s a compliant AI that isn’t quite human.

In the awesome show, Black Mirror, one episode features a young woman who lost her husband. In her grief she turns to a company that promises to give her at least a partial experience of her husband. They sift through every picture, video, comment, and other online trace of the person and construct from that a virtual avatar. At first the avatar just texts with the wife, which then progresses to phone calls, and then finally to a full robotic avatar indistinguishable from the lost husband. Except – it is not really indistinguishable. It’s a compliant AI that isn’t quite human.

So-called grief tech is possible now and is getting more popular. This is another instance of technology creating a new ethical situation that we have to confront, and it is too early to really tell what the impact will be. There are companies, mostly in Asia, that will create the virtual avatar of a dead loved-one for you (one company charges $50,000 for the service). They don’t just scrub the internet, they will make hours of high definition video and interviews to create the raw material to train the AI. The result is a high fidelity visual avatar speaking in the voice of the deceased with a chat-bot mimicking their style with access to lots of information about their life.

The important question is not, how good is it. It’s already very good, and clearly it will get incrementally better. It will also likely get much cheaper. Eventually it will be an app on your phone. The question is – is all this a net positive and healthy experience or is it mostly creepy and unhealthy? I suspect the answer will likely be yes – both. It will depend on the individual and the situation, and even for the individual there are likely to be positive and negative aspects. Either way – we are about to find out.

Continue Reading »

May

14

2024

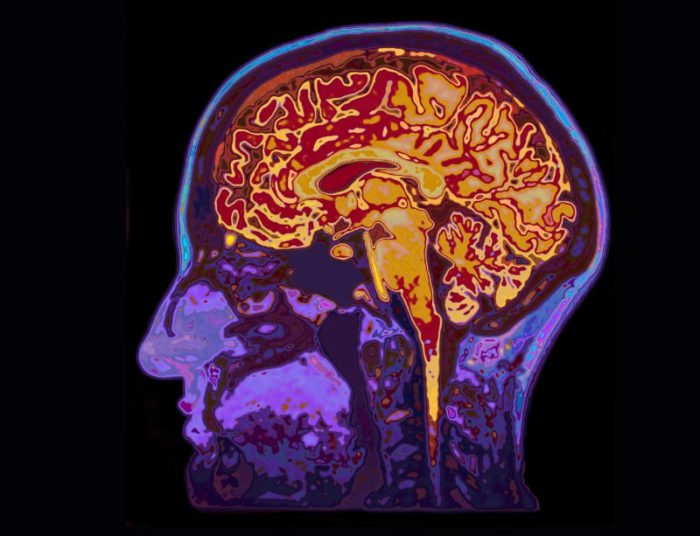

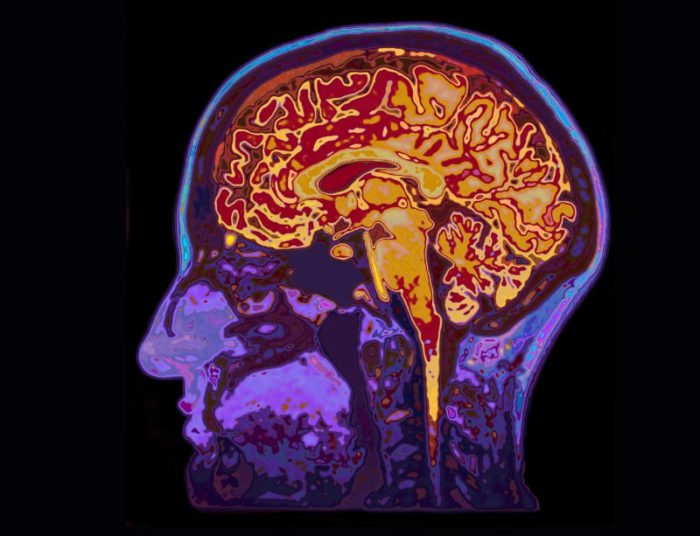

One of the most difficult situations that a person can face is to have a loved-one in a critical medical condition and have to make life-or-death medical decisions for them. I have been in this situation many times as the consulting neurologist, and I have seen how weighty this burden can be on family members. Advanced directives are helpful, but they cannot predict every possible situation or anticipate every medical nuance, so still, decisions have to be made.

One of the most difficult situations that a person can face is to have a loved-one in a critical medical condition and have to make life-or-death medical decisions for them. I have been in this situation many times as the consulting neurologist, and I have seen how weighty this burden can be on family members. Advanced directives are helpful, but they cannot predict every possible situation or anticipate every medical nuance, so still, decisions have to be made.

One thing is also clear – the better we are able to predict outcomes, the easier decision-making becomes. Uncertainty is the most difficult aspect of choosing, for example, whether or not to withdraw life-saving interventions. For this reason there has been a lot of research trying to help do exactly that – predict outcomes in various situations of neurological injury, so at least family members can make the most informed decision possible.

But one thing that doctors do not have, as we are fond of saying, is a crystal ball. We cannot say what an individual’s outcome will be, only make statistical statements based on predictive variables. Still, statistics can be extremely helpful.

A recent study adds to the literature addressing this question. They look at the outcomes of 146 adults with severe traumatic brain injury admitted to an ICU. They looked at whether or not there was withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment (WLST) and compared the characteristics of both groups. Not surprisingly, those who were WLST + were older on average and had more severe injury. The researchers also looked at those who were WLST – (did not have withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment) and tracked their outcomes.

Continue Reading »

May

13

2024

There is an interesting disconnect in our culture recently. About 90% of people claim that they verify information they encounter in the news and on social media, and 96% of Americans say that we need to limit the spread of misinformation online. And yet, the spread of misinformation is rampant. Most people, 74%, report that that they have seen information online labeled as false. Only about 60% of people report regularly checking information before sharing it. And a relatively small number of users spread a disproportionate amount of misinformation.

Of course, what is considered “misinformation” is often is the eyes of the beholder. We tend to silo ourselves in information ecosystems that share our worldview, and define misinformation relative to our chosen outlets. Republicans and Democrats, for example, trust completely different sources of news, with no overlap (in the most trusted sources). What’s fake news on Fox, is mainstream news on MSNBC, and vice versa. There is not only a difference in what is considered real vs fake news, but how the news is curated. Choosing certain stories to amplify over others can greatly distort one’s view of reality.

Misinformation is not new, but the networks of how it is created and shared is changing fairly quickly. If we all agree we need to stem the tide of misinformation, how do we do it? As is often the case with big social or systemic questions like this, we can take a top-down or bottom-up approach. The top-down approach is for social media platforms and news outlets to take responsibility for the quality of the information being spread on their watch. Clear misinformation can be identified and then nipped in the bud. AI algorithms backed up by human evaluators can kill a lot of misinformation, if the platform wants. Also, they can choose algorithms that favor quality and reliability over sensationalism and maximizing clicks and eyeballs. In addition, government regulations can influence the incentives for platforms and outlets to favor reliability over sensationalism.

Continue Reading »

May

09

2024

Last month I wrote about Havana Syndrome, the claim that a number of American and Canadian diplomats and military personnel were the targets of some sort of directed energy weapon attack causing symptoms of headache, disorientation, nausea, and sometimes associated with an auditory sensation. The point of the article was to do a plausibility analysis, based on what information I could find. I concluded:

Last month I wrote about Havana Syndrome, the claim that a number of American and Canadian diplomats and military personnel were the targets of some sort of directed energy weapon attack causing symptoms of headache, disorientation, nausea, and sometimes associated with an auditory sensation. The point of the article was to do a plausibility analysis, based on what information I could find. I concluded:

“So far it seems that the objective evidence favors the “mass delusion” hypothesis. This is similar to “sick building syndrome” and other health incidents where a chance cluster of symptoms leads to widespread reporting which is followed by confirmation bias and the background noise of stress and symptoms focusing on the alleged syndrome. This explanation, at least, cannot be ruled out by current evidence.”

But I also thought we could not rule out (“rule out” is a strong position) that some of the initial cases may have been a genuine external attack. Part of my point was to caution skeptics about landing prematurely on a skeptical narrative and then biasing any further analysis toward that narrative. Sometimes information is messy, and there are legitimate points on more than one side. Don’t use bad arguments even to defend legitimate skeptical positions.

Specifically, I wondered if Havana Syndrome were more like some prior mass delusions, where there was a core of genuine cases. The Pokemon seizure panic of the 1990s is a good example – most of the cases were some form of mass delusion, but about 10% were actually photosensitive seizures in susceptible individuals. So, how do we distinguish between 100% mass delusion and just mostly mass delusion? Arguments and evidence that some of the cases were not compatible with external attack or were clearly some form of hypervigilance, anxiety, or delusion do not make the distinction.

Continue Reading »

May

06

2024

Generally speaking the mainstream media does a terrible job of reporting anything in the realm of pseudoscience or the paranormal. The Washington Post’s recent article on children who apparently remember their past lives is no exception. Journalists generally don’t have the background or skill set necessary to deal with these often complex topics. They also don’t seem to care, looking at such stories as “fluff” pieces and see nothing but their click-bait potential. Almost universally missing from such pieces in effective skepticism. At best you may get some token skepticism, buried deep in the article, and usually immediately nullified by another anecdote or unchallenged claim. Such pieces, if they do rely on experts, focus on believers.

Generally speaking the mainstream media does a terrible job of reporting anything in the realm of pseudoscience or the paranormal. The Washington Post’s recent article on children who apparently remember their past lives is no exception. Journalists generally don’t have the background or skill set necessary to deal with these often complex topics. They also don’t seem to care, looking at such stories as “fluff” pieces and see nothing but their click-bait potential. Almost universally missing from such pieces in effective skepticism. At best you may get some token skepticism, buried deep in the article, and usually immediately nullified by another anecdote or unchallenged claim. Such pieces, if they do rely on experts, focus on believers.

I have written before about reincarnation. The Post article focuses on the same researcher, Stevenson, who always gets cited, because of his large body of research. The post article, in the end, is just regurgitating the same old arguments and evidence that has already been picked over by skeptics.

The lead anecdote is of a toddler who has an imaginary friend, Nina, and begins to weave increasingly details stories about Nina and her life. The detail that gets her parents most interested is when their daughter says, “Nina has numbers on her arm and it makes her sad.” This was interpreted as a memory from a Nazi concentration camp. There are basically two ways to interpret such behavior by children – either they are genuine memories of a past life (or some other source of actual memories), or they are fantasies. Here is a typical line of argument from the Post article:

She explained that at age 2 or 3, children engage in fantasy play, but they are not likely to fabricate a statement involving their primary relationships. In other words: Saying “You’re not my mom” or “I want my other parents” or “Where are my children?” — common among these cases — is not something you would typically expect a very young child to say, let alone repeat insistently. “It doesn’t sound like confusion,” Klein says. “It sounds like a real statement. And young children just don’t make this kind of thing up.”

Continue Reading »

May

03

2024

If all goes well, Boeing’s Starliner capsule will launch on Monday May 6th with two crew members aboard, Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams, who will be spending a week aboard the ISS. This is the last (hopefully) test of the new capsule, and if successful it will become officially in service. This will give NASA two commercial capsules, including the SpaceX Dragon capsule, on which it can purchase seats for its astronauts.

If all goes well, Boeing’s Starliner capsule will launch on Monday May 6th with two crew members aboard, Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams, who will be spending a week aboard the ISS. This is the last (hopefully) test of the new capsule, and if successful it will become officially in service. This will give NASA two commercial capsules, including the SpaceX Dragon capsule, on which it can purchase seats for its astronauts.

If successful this will fulfill NASAs Commercial Crew Program (CCP) – it decided, rather than building its own next generation space capsule, it would contract with commercial companies. After an initial evaluation phase it chose two companies, Boeing and SpaceX, to get the contracts. Initially the two projects were neck and neck, but to its credit SpaceX was able to complete development first, with its Dragon 2 capsule going into service in 2020. Boeing now hopes to be the second commercial company to have a NASA approved crewed capsule.

There is obviously a lot riding on this final test flight on Monday, given the recent difficulties that Boeing has had. Its hard-earned reputation for aerospace excellence has been significantly tarnished by recent failures of its jetliners which seem to have been due to systemic problems with quality control within Boeing, and a corporate culture that no longer seems dedicated to quality and safety first. Let’s hope the space capsule division does not have the same issues.

Continue Reading »

May

02

2024

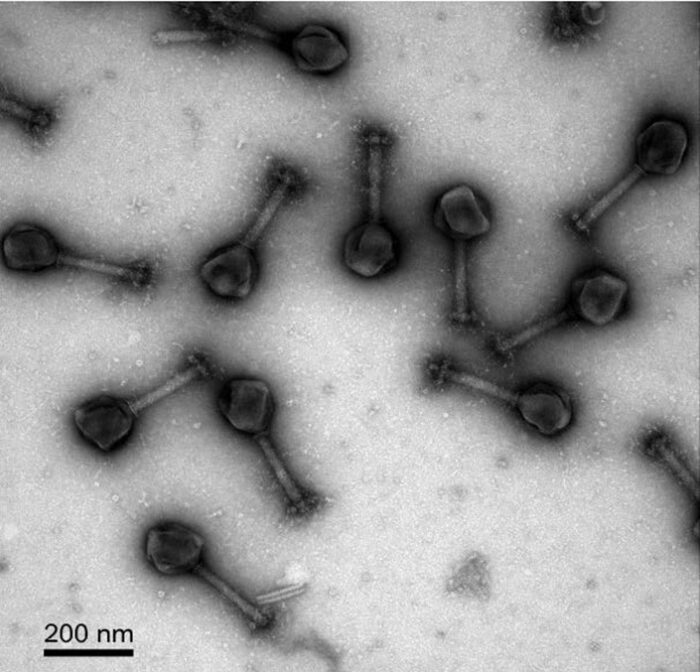

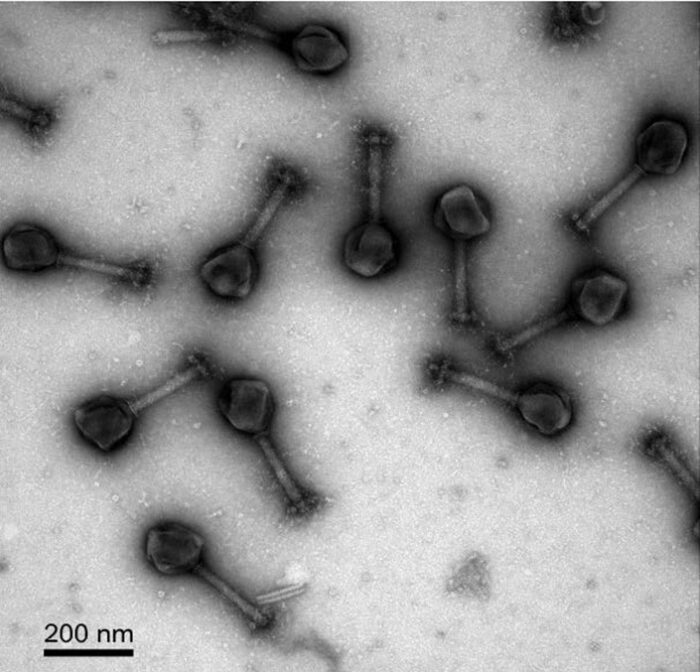

Bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria, are the most abundant form of life on Earth. And yet we know comparatively little about them. But in recent years phage research has taken off with renewed interest. This is partly driven by the availability of CRISPR-based tools for studying genomes. Interestingly, CRISPR itself is a gene-editing tool that derives from bacteria and archaea, which evolved the system as a defense against viruses that infect them and alter their genome. Now we are using CRISPR to investigate those very viruses, and perhaps use that knowledge as a tool to fight bacterial infections. Bacteria may have handed us the tools to fight bacteria.

Bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria, are the most abundant form of life on Earth. And yet we know comparatively little about them. But in recent years phage research has taken off with renewed interest. This is partly driven by the availability of CRISPR-based tools for studying genomes. Interestingly, CRISPR itself is a gene-editing tool that derives from bacteria and archaea, which evolved the system as a defense against viruses that infect them and alter their genome. Now we are using CRISPR to investigate those very viruses, and perhaps use that knowledge as a tool to fight bacterial infections. Bacteria may have handed us the tools to fight bacteria.

Most phage viruses are small, with genomes smaller than 200 kbp (kilo-base pairs). But a very few (93 so far) are larger than this, and known as jumbo phage viruses. The largest of these, Bacillus megaterium, is 497 kbp, which is only 87 kbp smaller than the smallest known bacterium, Mycoplasma genitalium. So essentially these are viruses that are almost as big as bacteria.

The jumbo phage viruses have been especially difficult to study for various technical reasons. For one, the filters that separate viruses from bacteria tend to trap the jumbo phages also. The genome has also been difficult to get access to. But CRISPR is changing that, giving us new tools to investigate these viruses. Researchers have recently published some interesting findings. When some jumbo viruses infect a bacterium they form a pseudonucleus that functions similar to the nucleus in eukaryotic cells, meaning that it is a walled-off section within the bacteria containing the viral genome. The purpose of forming this viral nucleus is to protect the genome from the bacterium, which will try to destroy or disable it before it can replicate.

Continue Reading »

In the awesome show, Black Mirror, one episode features a young woman who lost her husband. In her grief she turns to a company that promises to give her at least a partial experience of her husband. They sift through every picture, video, comment, and other online trace of the person and construct from that a virtual avatar. At first the avatar just texts with the wife, which then progresses to phone calls, and then finally to a full robotic avatar indistinguishable from the lost husband. Except – it is not really indistinguishable. It’s a compliant AI that isn’t quite human.

In the awesome show, Black Mirror, one episode features a young woman who lost her husband. In her grief she turns to a company that promises to give her at least a partial experience of her husband. They sift through every picture, video, comment, and other online trace of the person and construct from that a virtual avatar. At first the avatar just texts with the wife, which then progresses to phone calls, and then finally to a full robotic avatar indistinguishable from the lost husband. Except – it is not really indistinguishable. It’s a compliant AI that isn’t quite human.

One of the most difficult situations that a person can face is to have a loved-one in a critical medical condition and have to make life-or-death medical decisions for them. I have been in this situation many times as the consulting neurologist, and I have seen how weighty this burden can be on family members. Advanced directives are helpful, but they cannot predict every possible situation or anticipate every medical nuance, so still, decisions have to be made.

One of the most difficult situations that a person can face is to have a loved-one in a critical medical condition and have to make life-or-death medical decisions for them. I have been in this situation many times as the consulting neurologist, and I have seen how weighty this burden can be on family members. Advanced directives are helpful, but they cannot predict every possible situation or anticipate every medical nuance, so still, decisions have to be made. Last month

Last month  Generally speaking the mainstream media does a terrible job of reporting anything in the realm of pseudoscience or the paranormal.

Generally speaking the mainstream media does a terrible job of reporting anything in the realm of pseudoscience or the paranormal.  If all goes well, Boeing’s Starliner capsule

If all goes well, Boeing’s Starliner capsule Bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria, are the most abundant form of life on Earth. And yet we know comparatively little about them. But in recent years phage research has taken off with renewed interest. This is partly driven by the availability of CRISPR-based tools for studying genomes. Interestingly, CRISPR itself is a gene-editing tool that derives from bacteria and archaea, which evolved the system as a defense against viruses that infect them and alter their genome. Now we are using CRISPR to investigate those very viruses, and perhaps use that knowledge as a tool to fight bacterial infections. Bacteria may have handed us the tools to fight bacteria.

Bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria, are the most abundant form of life on Earth. And yet we know comparatively little about them. But in recent years phage research has taken off with renewed interest. This is partly driven by the availability of CRISPR-based tools for studying genomes. Interestingly, CRISPR itself is a gene-editing tool that derives from bacteria and archaea, which evolved the system as a defense against viruses that infect them and alter their genome. Now we are using CRISPR to investigate those very viruses, and perhaps use that knowledge as a tool to fight bacterial infections. Bacteria may have handed us the tools to fight bacteria.