Jun 27 2022

Flu Vaccines Associated With Reduced Alzheimer’s Risk

A recent large population-based study shows a significant reduction in the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in older adults who received one or more flu vaccines. This follows previous studies showing a similar protective effect for other adult vaccines, and raises interesting questions regarding possible mechanisms.

A recent large population-based study shows a significant reduction in the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in older adults who received one or more flu vaccines. This follows previous studies showing a similar protective effect for other adult vaccines, and raises interesting questions regarding possible mechanisms.

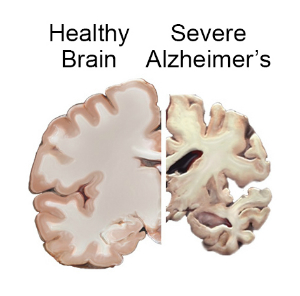

AD is a degenerative neurological disease which is the most common cause of dementia, which is a syndrome of chronic global cognitive impairment. The prevalence of AD is about 6.5 million people in the US. The risk of developing AD increases with age, with 10.7% of those 65 and older being affected. AD is more than just having dementia, it is a specific disease that can only be confirmed at this time by looking at the brain. There are pathological changes including plaques and tangles. Imaging can also reveal diffuse cortical atrophy (shrinkage of the brain). Electroencephalogram typically shows slowing, indicating reduced cortical activity. There are many markers of AD that can be identified in the blood or spinal fluid, but none are good enough to be used in routine clinical evaluation.

The causes of AD are complex and not yet fully understood. In brief, a lot of stuff happens on the way towards brain cells dying but it’s hard to known which stuff is driving the process and which are a result of the process. It therefore has been difficult to device treatments to slow or prevent progression. For my entire career as a neurologist it seemed as if we were getting close to a significant clinical breakthrough, but we’re still waiting. Tremendous progress has been made, but nothing that amounts to a disease-modifying treatment.

Prevention before the disease becomes clinically apparent would be ideal. We know that controlling blood pressure and other markers of cardiovascular health are extremely important in reducing the risk of AD. We also know that physical exercise is important, as well as keeping mentally active. Sometimes, however, it is difficult to separate preventive measures that actually delay or slow the onset of AD vs those that mask the onset through creating a higher baseline of cognitive function. Regardless, all of the above are good lifestyle choices.

One of the interesting variables in AD is the role of the immune system. Whenever there is cell death there will be an immune reaction, if for nothing else than to clean up the dead cells. Therefore it’s difficult to interpret the implications of markers of inflammation. It’s also possible that reactive inflammation does not cause AD but can worsen it or hasten the progression. There has been a lot of research into treating AD with anti-inflammatories of one type or another, but nothing has shown clear efficacy so far and there are no approved anti-inflammatory drugs for AD. The one drug approved to treat AD, aducanumab, is not an anti-inflammatory and rather targets amyloid beta, but the approval of this drug is highly controversial.

One of the many questions surround AD is the role of viral and other infectious agents. Viruses in many ways are still the “boogeymen” of neurology. We know viral infections are common, but there are many more viruses out there than we currently can identify. We also know that viral infections can directly target neurological tissue. Also, viral infections can trigger post-infectious immune responses which then cause further damage, and may even trigger chronic neurological disease. For many neurological diseases for which the cause is mysterious viruses are raised as a possible cause, and AD is no exception. This hypothesis resulted in some preliminary studies in which it was explored whether vaccines against common viral infections reduce the risk of AD. Early results show a possible protective effect.

These preliminary studies resulted in the current study, so let’s get to the detail. Here are the results:

“From the unmatched sample of eligible patients (n = 2,356,479), PSM produced a sample of 935,887 flu–vaccinated-unvaccinated matched pairs. The matched sample was 73.7 (SD, 8.7) years of age and 56.9% female, with median follow-up of 46 (IQR, 29–48) months; 5.1% (n = 47,889) of the flu-vaccinated patients and 8.5% (n = 79,630) of the flu-unvaccinated patients developed AD during follow-up. The RR was 0.60 (95% CI, 0.59–0.61) and ARR was 0.034 (95% CI, 0.033–0.035), corresponding to a number needed to treat of 29.4.”

That’s a relative risk reduction of 40% with an absolute risk reduction from 8.5% to 5.1% (3.4%). That is a significant reduction. This is a very powerful study because of the very large N, and so these results are highly statistically significant. So it’s very likely that this correlation is real. But the first question for this kind of data is – what is the cause and effect? Generically we always have to consider three possibilities – A causes B, B causes A, or A and B or caused by C (or D or E). In this case one likely interpretation is that getting flu vaccines prevents or delays the onset of AD. There was a dose-response effect, with greater number of flu vaccines being more protective, which supports this interpretation.

Is it possible that people with AD are less likely to get the flu vaccine, perhaps because their dementia reduces their overall healthcare compliance? This is unlikely given that the subjects did not have a clinical diagnosis of dementia at the beginning of the study, and when they would have received the flu vaccines. So we would have to assume they had mild dementia, enough to reduce their chance of getting vaccinated but not enough to get diagnosed. This seems unlikely.

The real variable here is cofounding factors – that some other factors may contribute to getting vaccinated and a reduced risk of getting AD. This could be the generic “healthy user effect” – people who get vaccinated may engage in other healthy behaviors, one or more of which reduces risk of AD. Perhaps they are also more compliant with their blood pressure medication. The researchers, of course, looked at this. Trying to control for confounding factors is standard, it’s just difficult to capture them all. They report:

“For each covariate, the last measurement within the look-back period was used as the baseline value. Covariates included demographics, physical and psychiatric comorbidities, sustained use of medications potentially related to probability of influenza vaccination and/or incident AD (either directly as an effect of the medication or indirectly as an indicator of a relevant comorbidity), number of routine well visits during the look-back period, and total number of health care encounters during the look-back period (as a proxy for overall healthcare utilization rate).”

Still, that seems fairly thorough. So while we cannot rule out confounding factors, and it would be nice to confirm these results, they are looking fairly solid. If we assume that the flu vaccine in genuinely protective against AD, what are the possible mechanisms? The most straightforward interpretation is that getting the flu virus, even with a mild or subclinical infection, can increase the risk of AD. Therefor the vaccine reduces this risk. But a more complex immune relationship may be at work. Perhaps the flu vaccine itself activates the immune system in a way that reduces overall AD risk. Perhaps this immune activity uses up resources that would otherwise be available for whatever immune activity contributes to AD.

Further study is clearly needed. Specifically, the researchers want to look at whether or not flu vaccines alter the course of AD after diagnosis. Meanwhile, this is compelling evidence that there is likely a protective effect for flu vaccines against developing AD. Since it’s already a good idea to get the flu vaccine every year, this is one more reason.