Aug 09 2016

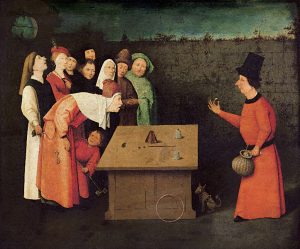

Making the Non-Existent Disappear

If I told you I could make something nonexistent disappear, you probably would not be very impressed with that as a magic trick. However, magic is all about misdirection. If I could make you think you saw an object that was never there, and then make it disappear, that could be quite impressive.

If I told you I could make something nonexistent disappear, you probably would not be very impressed with that as a magic trick. However, magic is all about misdirection. If I could make you think you saw an object that was never there, and then make it disappear, that could be quite impressive.

Psychology and Magic

Increasingly psychologists, neuroscientists, and magicians are converging upon a model of how our brains construct our perceptions of reality. Magicians actually had a head start as they have been working out practical ways to fool human perception for centuries. Psychologists started taking note in the late 19th century, but really have only been seriously examining the techniques of magicians in the last decade or so. Psychologists now routinely use magic tricks as part of experimental setups.

The basic picture that has emerged is that our sensory perceptions have both bottom-up and top-down components. The bottom-up components are essentially using the raw sensory input and constructing an image from that, then passing that construction on to higher brain levels that interpret the image and give it emotional meaning. Top-down construction works the opposite way, with the higher brain areas communicating their expectations to the primary sensory areas and influencing their construction.

When our brain constructs an image, therefore, there are two simultaneous directions of communication. The primary sensory areas communicate to the interpretive areas, while the interpretive areas communicate back to the primary sensory areas. There is actually also horizontal communication to other sensory areas. What we see, for example, can affect what we hear.

There is a dynamic interplay among all this communication resulting in a constructed perception of reality that is partly based on sensory input and partly based upon expectation and interpretation. We only notice this process when it breaks down, during optical illusions, for example.

(I wrote last year about a study showing that hallucinations may result from a shift in the dynamic balance toward top-down construction of images.)

Psychologists try to break down this construction in order to tease apart the various elements. Magicians try to break down this construction to create entertaining illusions. Collaboration was natural.

Perceiving the Non-existent

In the new study psychologists take a common magical trick and simplify it to isolate one variable. The trick involves throwing a ball or similar object up into the air twice, then on the third time dropping the object out of site just before pantomiming the action of throwing it up into the air again. Many viewers will see the ball rise into the air and then vanish.

Magicians eventually discovered that you don’t even need to prime viewers with the initial throws. You can fake throw the ball into the air on the first go, and many viewers will still see the ball. Their expectations are communicating to their primary visual cortex and constructing an image of a ball that is no longer there.

Magicians have learned to use various cues to enhance such illusions. They may verbally create an expectation. They also use social cues, like where they direct their vision. Their eyes will follow the non-existent ball, encouraging our brains to top-down perceive it. Further, the entire act can create a meta-expectation that something fantastic will occur. Everyone knows that magic is not real, but the magician creates the impression that they have fantastic skill, and are doing something very complex. The astonishment of those around us may also encourage us to be astonished.

In the current study psychologists used this trick stripped of any other cues. Subjects viewed a number of silent videos in which magicians made an object that was initially there seem to disappear, where nothing magical happened, and where there was never an object but the magician pantomimed making it vanish.

In their study 32% of the subjects reported seeing the non-existent object, and 11% named a specific object. This further supports the top-down model of perception – we can be made to “see” objects that are not there.

Seeing in Everyday Life

These phenomena are not isolated to magician performances or psychological studies. This is how our visual system works every day. Our vision is actually quite poor. Everything outside of our fovea, which is a small patch of high density on the retina, representing your thumbnail at arms length, is actually just a blur. Visual information is incomplete and ambiguous.

Our brains needed to evolve a mechanism to take this poor ambiguous information and construct a seamless experience of reality that was highly functional. We need to quickly recognize objects, see how they are moving, and know if they represent a threat. Our vision is processed to create continuity, and to project a little into the future to compensate for the lag in brain processing. It also takes two-dimensional information and creates a three-dimensional experience, with apparent size, distance, velocity, and relative position.

We can go from blurry ambiguous information to a seemingly detailed image of a tiger running through a sun-dappled forest because our knowledge and expectations tell our visual cortex how to fill in all those details. In the process some information is enhanced, other information is deleted, and missing information is created. Our brains make the most likely assumption of what we are seeing, then constructs the image to match those assumptions. Our brains, for example, assume that smaller things are farther away and will construct our perceptions accordingly.

Also imagine the effect that top-down processing can have when emotions are high. This can be during a crime or accident, or while investigating an allegedly haunted house, hunting for Bigfoot, or during an alleged encounter with a UFO. Even if we just consider the 11% of people who seem to be especially suggestible (which could just mean the balance of sensory construction is shifted toward top-down influence), they can generate a lot of sightings and false information.

It is no wonder that there are many stories of fantastical encounters out there. It is also not surprising that these encounters tend to match the prevailing beliefs in the culture, which suggests they are being driven by top-down expectation, not bottom-up sensory input.

All of this is without even considering the effects of memory, which itself is a construction and tends to morph over time to match the prevailing narrative.

All of this is why when people say, “I know what I saw,” my answer is, “No you don’t. You have a constructed memory of a constructed perception all biased by your expectations and beliefs.”

People generally are not lying when they report seeing fantastic things, any more than the subjects who report they saw the magician throw a specific object into the air are lying. They just have human brains.