Mar 04 2021

Cuttlefish Pass Marshmallow Test

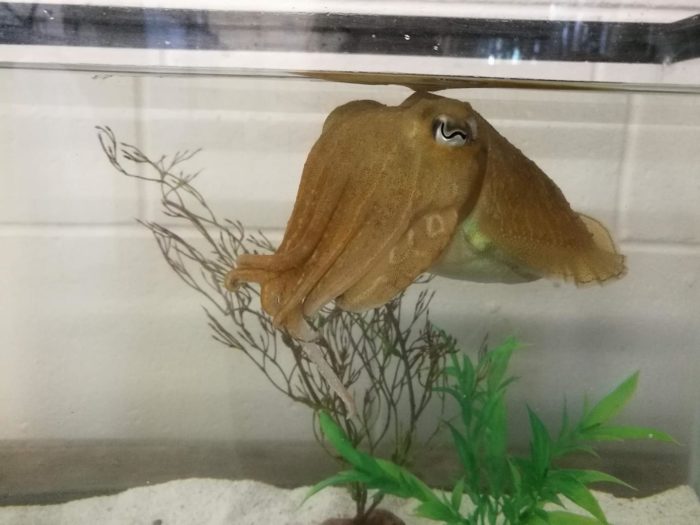

Cuttlefish are amazing little critters. They are cephalopods (along with octopus, quid, and nautilus), they see polarized light and can use that to change their skin color to match their surroundings. They have eight arms and two tentacles, all with suckers, that they use to capture prey. They, like other cephalopods, are also pretty smart. And now, apparently, they are also in the very elite club of animals who can pass the marshmallow test.

Cuttlefish are amazing little critters. They are cephalopods (along with octopus, quid, and nautilus), they see polarized light and can use that to change their skin color to match their surroundings. They have eight arms and two tentacles, all with suckers, that they use to capture prey. They, like other cephalopods, are also pretty smart. And now, apparently, they are also in the very elite club of animals who can pass the marshmallow test.

The “marshmallow test” is a psychological experiment of the ability to delay gratification. The basic study involves putting a treat (like a marshmallow, but it can be anything) in front of a young child and telling them they can have it now, or they can wait until the adult returns at which time they will be given two treats. The question is – how long can children hold out in order to double their treats? The interesting part of this research paradigm are all the associated factors. Older children can hold out longer than younger children. The greater the reward, the more children can wait for it. Children who find ways to distract themselves can hold out longer.

For decades the test and all its variations was interpreted as a measure of executive function, and correlated with all sorts of things like later academic and economic success. However, more recent studies have found (unsurprisingly) that there can be confounding factors not previously recognized. For example, children from insecure environments have not reason to trust that adults will return with more treats and therefore take what is in front of them. This could be seen as an adaptive response to their environment.

In any case – the core phenomenon seems robust. At the very least it requires a certain amount of self-control and perhaps some metacognition to be able to inhibit a desired behavior for future gain. Which animals have passed some version of this test? Chimpanzees are the best documented. Not only will they wait for a larger reward, they will find ways to distract themselves to help them do it (demonstrating metacognition – self-awareness of their own mental state). Some other primates, corvids, parrots, and dogs have also demonstrated some ability at delayed reward. This list makes sense – these are all animals who have demonstrated cognitive abilities rare in the animal world and associated with humans.

We can now add cuttlefish to the list, and this also makes sense because cephalopods have also previously demonstrated good problem-solving skills. The research not only shows that cuttlefish can delay gratification – wait for a greater reward – but that smarter cuttlefish were able to do it better. The researchers tested the ability of the cuttlefish to learn associations, and the ones who performed better were able to hold out longer on the marshmallow test. This reinforces the notion that some degree of cognitive ability is required in order to delay gratification.

This may also be a specific skill, not just a marker of overall cognitive power. In other words, perhaps there is some specific selective pressure that favors individuals with the brain wiring to delay reward. What would that be in cuttlefish? This is where evolutionary speculation comes into play, but this is what the authors surmise. Cuttlefish are predators, but they are also prey. They use camouflage and hide in order to avoid being eaten, which means before they get to eat they have to wait patiently until the coast is clear. A juicy morsel may swim by, but the cuttlefish has to stay hidden because there are also predators nearby. Cuttlefish who could not control themselves were more likely to get eaten.

This scenario makes sense, and perhaps could be tested by seeing, for example, if there is a correlation between average wait times for hunting prey and chance of becoming prey among cuttlefish. In any case – there is probably a combination of overall general intelligence and the specific ability to delay gratification at work here. Another way to look at this, which fits with the evidence, even with people, is that gratification can be delayed if there is another cognitive factor at work that is stronger than the immediate desire to obtain the treat.

This seems to come down to math – various factors are being weighed affecting the final decision. In the case of the marshmallow test, it is not just a binary choice – there is also the amount of time that an individual can hold out. So this experimental paradigm may be optimal for weighing various factors. As mentioned, for example, the bigger the later reward, the longer people can hold out on average, without any apparent upper limit. It’s a calculation. Much of our decision-making may be similarly calculated (at least in the aggregate), just not as obvious.

It’s hard for us to imagine what is happening inside the mind of a cuttlefish, a product of a distant evolutionary path. But there is some convergence here, probably because some things are fundamental and basic, like calculating optimal outcomes.