Jan 10 2020

The Polio Dilemma

In 1988 there were 350,000 cases of polio worldwide. Polio is a virus that attacks the nervous system and can cause paralysis. Effective vaccines had already significantly reduced polio cases in developed nations, but it was still a scourge in poor countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) and others formed the Global Polio Eradication Initiative with the goal of eradicating polio from the world by the year 2000. They were partly successful. Their massive vaccine campaigns reduced the number of cases to 719 by 2000, and by a total of 99.99%, to just 33 cases in 2018. But the program failed to completely eradicate polio, and in this case close (while still a great reduction in disease) is not enough.

In 1988 there were 350,000 cases of polio worldwide. Polio is a virus that attacks the nervous system and can cause paralysis. Effective vaccines had already significantly reduced polio cases in developed nations, but it was still a scourge in poor countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) and others formed the Global Polio Eradication Initiative with the goal of eradicating polio from the world by the year 2000. They were partly successful. Their massive vaccine campaigns reduced the number of cases to 719 by 2000, and by a total of 99.99%, to just 33 cases in 2018. But the program failed to completely eradicate polio, and in this case close (while still a great reduction in disease) is not enough.

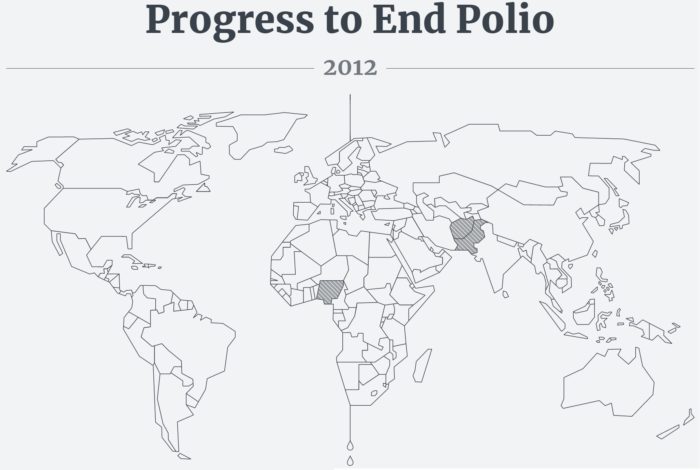

Polio is a virus that has the potential to be eradicated, meaning completely eliminated from the world, because there is no non-human reservoir. Other viruses, like ebola, can spread in animals, which makes it impossible to eradicate from the world just by vaccinating humans. So eradicating polio is an achievable goal, and we got real close in 2002. Wild cases of polio were limited to three countries, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. Elimination failed in these countries entirely because of political unrest which itself resulted in anti-vaccine sentiments. The vaccine program was portrayed as a Western conspiracy, reducing compliance.

Since that time the GPEI has been fighting a somewhat losing battle, unable to snuff out the last embers of polio. Unfortunately, in 2019 the effort has faced it worse year since 2000, because of continued political unrest, but also because biology has simply caught up to the effort. The story is a bit complex, but here is the overview.

There are three strains of polio virus, wild type 1, 2, and 3. The primary effort to eradicate polio was through a trivalent live attenuated virus vaccine, one that contains weakened versions of all three polio strains. A live virus vaccine uses viruses that have been genetically gimped, so they can cause a mild infection and strong immunity, but are not virulent enough to cause any disease. There is an advantage and disadvantage to live virus over a killed virus or viral particle vaccine. The live virus in this case causes stronger immunity, enough to fully prevent the shedding and spread of virus. So this is most useful in an eradication campaign, as opposed to simply one trying to minimize disease.

But the downside of a live attenuated virus vaccine is that the virus can occasionally undergo a spontaneous mutation that happens to reverse the attenuation, so it reverts to becoming more virulent and able to cause disease. Such events are unavoidable – it’s just a matter of statistics. The live vaccines, therefore, reduce disease but occasionally cause their own outbreaks of vaccine-type virus. But you can manage and contain these outbreaks.

The GPEI has been tracking each of the three known strains of polio. The last detected case of wild serotype 2 was from 1999. So, in 2016 they replaced the trivalent vaccine with a divalent one, containing serotypes 1 and 3 but not 2. Why take a chance on causing a type 2 outbreak when there is no wild type 2 left? There could still be type 2 outbreaks from existing trivalent vaccines and those already vaccinated for a few years, but they could be contained using a type 2 specific monovalent vaccine as needed to limit the spread. So they crossed their fingers and made the switch. Unfortunately, outbreaks of vaccine-derived serotype 2 polio have been increasing, tripling in Africa between 2018 and 2019.

This is a problem, because young children, those vaccinated since the switch, have no immunity to type 2, so any outbreaks have more fertile soil. Also the vaccine virus has regained enough virulence to continue to spread. The WHO is worried it will jump continents, and set back eradication efforts by years. The GPEI now finds itself in a dilemma.

One strategy going forward could be to simply do what they have been doing. Use the divalent vaccine, and then swoop in with the monovalent type 2 vaccine to quash any outbreaks, and hope that they reduce spread more than they cause further vaccine-derived outbreaks. The problem with this strategy is that they are running out of their stockpiles of the monovalent type 2 vaccine. If they run out, then they will not be able to contain the spread of type 2. Replacing the stockpile can take years.

The second strategy is to revert to the trivalent vaccine so that there is universal coverage for all three strains. This would be difficult from a PR perspective (which is important to the effort) because it represents a failure of the current strategy, forcing the effort to go backwards to the older vaccine. Also, it will take a few years to ramp up production of the currently abandoned vaccine.

The third strategy is to wait for a new vaccine, a new live oral type 2 specific vaccine in which the virus has multiple mutations that render it less likely to revert to the virulent type. This vaccine is still in testing. We could start using the vaccine based on the preliminary evidence, and hope that it works out. Or we can wait for the more definitive clinical trials, and risk type 2 outbreaks worsening and jumping continents in the meantime.

At this point there is no perfect option. The GPEI is going to have to take a calculated risk one way or the other. This is frustrating, because we are so close to eradicating polio forever. But even if one case exists in the world, we have to continue vaccinating, which itself risks vaccine-induced outbreaks. That is why we need a massive effort to quickly eradicate the disease. We had our chance in the early 2000s, but could not quite get it done (like Isildur in Mount Doom), and now time is our enemy. Viruses mutate. The longer they are out there in the population, the greater the chance that some unfortunate mutation will occur.

I don’t know what decision the GPEI will make, but I hope it works out. I suspect we will tread water until the new type 2 vaccine is fully approved, and assuming it works as intended, then we can make another hard push for eradication. This will also require the world putting a lot of pressure on the remaining endemic countries to allow unfettered vaccination efforts. The actions of one small group of people in a remote country can affect the entire world.