Dec 01 2025

Cognitive Legos

We have all likely had the experience that when we learn a task it becomes easier to learn a distinct but related task. Learning to cook one dish makes it easier to learn other dishes. Learning how to repair a radio helps you learn to repair other electronics. Even more abstractly – when you learn anything it can improve your ability to learn in general. This is partly because primate brains are very flexible – we can repurpose knowledge and skills to other areas. This is related to the fact that we are good at finding patterns and connections among disparate items. Language is also a good example of this – puns or witty linguistic humor is often based on making a connection between words in different contexts (I tried to tell a joke about chemistry, but there was no reaction).

We have all likely had the experience that when we learn a task it becomes easier to learn a distinct but related task. Learning to cook one dish makes it easier to learn other dishes. Learning how to repair a radio helps you learn to repair other electronics. Even more abstractly – when you learn anything it can improve your ability to learn in general. This is partly because primate brains are very flexible – we can repurpose knowledge and skills to other areas. This is related to the fact that we are good at finding patterns and connections among disparate items. Language is also a good example of this – puns or witty linguistic humor is often based on making a connection between words in different contexts (I tried to tell a joke about chemistry, but there was no reaction).

Neuroscientists are always trying to understand what we call the “neuroanatomical correlates” of cognitive function – what part of the brain is responsible for specific tasks and abilities? There is no specific one-to-one correlation. I think the best current summary of how the brain is organized is that it is made of networks of modules. Modules are nodes in the brain that do specific processing, but they participate in multiple different networks or circuits, and may even have different functions in different networks. Networks can also be more or less widely distributed, with the higher cognitive functions tending to be more complex than specific simple tasks.

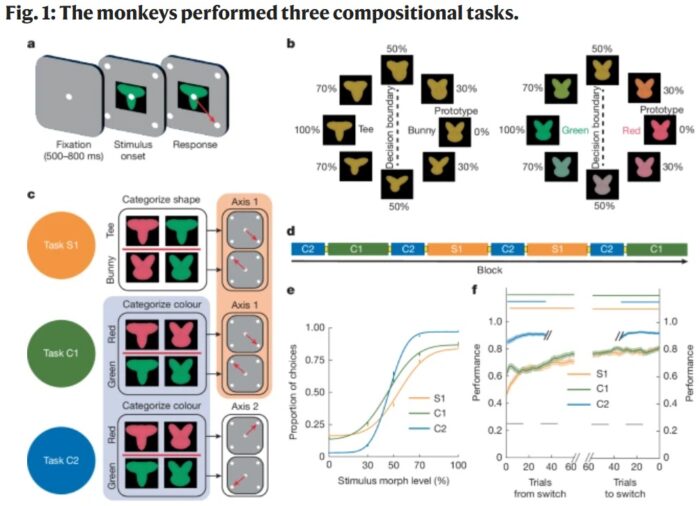

What, then, is happening in the brain when we exhibit this cognitive flexibility, repurposing elements of one learned task to help learn a new task? To address this question Princeton researchers looked at rhesus macaques. Specifically they wanted to know if primates engage in what is called “compositionality” – breaking down a task into specific components that can then be combined to perform the task. Those components can then be combined in new arrangements to compose a new task, like building with legos.

They taught the macaques different tasks, such as discriminating between shapes or colors. The tasks had a range of difficulty, for example they had to distinguish between red and blue, with some of the colors being vibrant and obvious while others were muted or ambiguous. To indicate which shape or color they were perceiving they had to look either to the upper left or the lower right on some tasks, or the upper right and lower left on others. Essentially they had to combine a sensory perception to a motor activity. The question was – when the tasks were shuffled, would they use the same brain components (or what the researchers call “subspaces”) in a new combination to perform the new task? And the answer is – yes, that is exactly what they did.

Obviously, this is a rather simple construct, and it is only one study, but the evidence is consistent with the compositionality hypothesis. More research will be needed to confirm these results for different tasks with more complexity, and of course to replicate these results in humans. I think the idea of compositionality makes sense, but not everything that makes sense in science turns out to be true. Some ideas in neuroscience are discarded when they turn out not to be true, like the notion of the “global workspace” (an area of the brain that was the common networking hub of all consciousness).

There is also already research indicating that compositionality is just one feature of learning that exists on a continuum (probably) with another feature of learning – interference. The way you measure interference is to train someone on task A, then train them on related task B, and then retest them on task A. If learning task B reduces their performance on task A, that is interference. You have probably experienced this as well – you sometimes have to “unlearn” a new task to go back to an older one. My family has two cars, one with regenerative braking and one without, with each requiring a slightly different driving style. With regenerative braking, when you lift off the gas it slows the car through resistance. Switching back and forth causes a bit of interference, and it takes a moment to adapt to the new task.

It turns out, humans and neural networks display similar patterns of compositionality and interference. People exist along a spectrum with “lumpers” transferring skills from one task to another more easily, but also displaying more interference, and “splitters” who do not transfer skills as much, but also do not suffer interference as much. It appears to be a tradeoff, with different people having different tradeoffs between these two features of learning. In other words, if you reuse cognitive legos to build new tasks, that will make it easier to learn new related tasks because you can repurpose existing skills. But then those legos are networked with other tasks, which can cause interference with previously learned tasks using the same legos. Or – you build an entirely new network for a new task, which takes more time but does not repurpose and therefore does not cause interference with previously learned tasks. Which is better? There is likely no simple answer, as it is probably very context dependent.

Further, if people fall along the lumper to splitter spectrum, is that consistent across cognitive domains? Can one person be a lumper for some kinds of tasks and a splitter for others? Can we start as a lumper, but then morph into a splitter if we switch among tasks frequently over time, thereby reducing interference? Will different learning mechanisms favor adopting a lumper vs splitter strategy? Sometimes I want to be flexible and adapt quickly, at other times I may want to invest the time to minimize interference as I switch among tasks. Is there a way to get the best of both worlds?

That’s the thing with interesting research, it usually provokes more questions than it answers. Lots to do.