Jul 17 2020

The Coming Population Bust

I often discuss the fact that the world’s population is set to approach 10 billion people by 2060 or so. Right now we are approaching 8 billion. This is a potentially serious issue, mainly for food security. We are already using most of the arable land on the planet, and will need to produce more food on the same, or hopefully less, land if we are to sustain these populations without devastating ecosystems (more than we already have). We also need to produce enough energy and goods while dealing with that whole global warming thing. So many people might find it interesting that some scientists are warning about a coming decline in human populations.

I often discuss the fact that the world’s population is set to approach 10 billion people by 2060 or so. Right now we are approaching 8 billion. This is a potentially serious issue, mainly for food security. We are already using most of the arable land on the planet, and will need to produce more food on the same, or hopefully less, land if we are to sustain these populations without devastating ecosystems (more than we already have). We also need to produce enough energy and goods while dealing with that whole global warming thing. So many people might find it interesting that some scientists are warning about a coming decline in human populations.

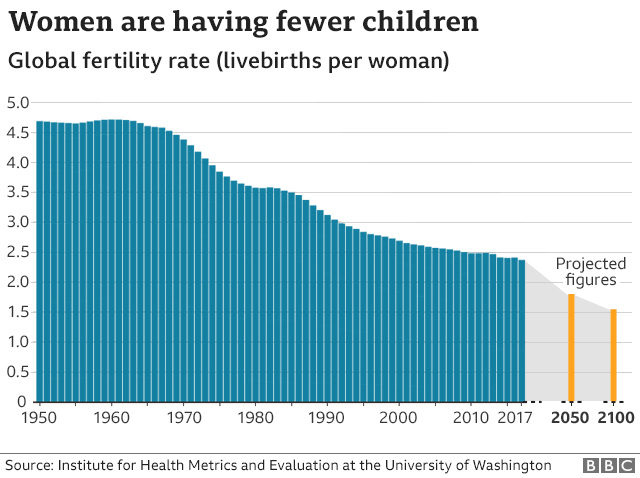

This all has to do with fertility rates, which have been dropping around the world. The drop is not uniform, but the global average fertility rate has declined over the last century from 4.6 to 2.4. Equilibrium level is a fertility rate of 2.1, and if the number drops below that, then population numbers decrease. Here is where things get tricky – extrapolating current trends into the future. We lack a proverbial crystal ball, and so have to make a lot of assumptions, which can prove incorrect. Even if the assumptions are reasonable, it’s hard to predict game-changers. These can come in the form of unanticipated technology, or radical social change. Even more subtle social change can shift the equations and make a big difference when you are extrapolating out 80 years. Did anyone 80 years ago predict anything meaningful about the world today? To be fair, many did, but they were broad brushstrokes like most people owning cars, and being able to communicate with anyone in the world by telephone. The question is – are the broad brushstrokes enough to predict trend lines in fertility rates, or will the unknown details derail these predictions?

Here’s what we do know. The primary reason for decreasing fertility rates is not biological, it’s social. It relates directly to improved rights for women, who can then choose to work, to use contraception, and to control how many children they have. This is an undeniable good thing – women should have these rights, and there is no going back (unless you envision a future much like Gilead in The Handmaiden). This is why, for those who think reducing the human population is a good thing, they should focus their efforts on women’s rights. That will accomplish their goal.

But why is this a potential concern? We can look at this question from several perspectives – the absolute population numbers worldwide, the distribution of population, and the change in population. What is the optimal one number of world population? That’s a tough question to answer, and depends on your perspective and priorities. Those who argue that the number should be less than it is today have some reasonable points. We do have a rather large footprint on the world’s ecosystems and reducing that footprint would be easier to sustain. On the other hand, people can be a critical resource, especially intellectually. More people can drive innovation, including ways to to more with less. There is also a quality of life issue. How crowded do you want the world to be? I don’t think there are objective answers to these questions, but perhaps we can agree in broad terms that the human population should not exceed or capacity to feed and care for people or our ability to manage our infrastructure without destroying the environment. I also think we should have the goal of preserving as much wildlife as possible.

What about distribution? The projections indicate that the more industrialized nations will have the largest drop in fertility rates, as they already are. Many countries are already below 2.1. Meanwhile, developing countries could still see a boom in population over the next century. This would cause a significant shift in population around the world, which likely would lead to increased pressure for immigration. This could be highly disruptive socially.

Perhaps the biggest issue, however, is the magnitude and direction of change in the population, rather than the absolute number or distribution. A falling population would invert the age pyramid. Instead of having more young people being productive and caring for fewer older people, we would have the reverse – fewer working-age people taking care of a growing population of older people. This could be a significant strain on society. This, I think, is what most worries scientists looking at this issue.

But again – this may not be a problem. What will the world look like in 60-80 years when the demographics start to shift? How much more productive will the average worker be? Will we have an army of robots to do most of the mundane work, and even take care of the elderly? What if we extend the healthy lifespan significantly, so that people can easily work into their 80s? This is the problem with extrapolating that far into the future, and more so as time goes on and the rate of technological and social change increases. If we had these inverted demographics – today – that would be a problem. But we cannot assume this will be true in 80 years.

This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t think about all this, anticipate these changes, and maybe even adjust policy to mitigate potential downsides. It does mean we have to take any projections into the future with a huge grain of salt.