Feb 16 2021

What Killed North America’s Megafauna?

Before around 13,000 years ago large mammals walked North America – the Mammoth, most famously, but also giant beavers, giant tree sloths, glyptodonts, and the American cheetah among them. By around 11,000 years ago they were all gone (38 genera, mostly mammals). Extinction is a natural part of the cycle of ecosystems, and no species lasts forever. But when paleontologists identify a pulse of extinctions, above the background rate, they call that an extinction event, and this definitely qualifies. Extinction events call out for answers – what was the cause?

Before around 13,000 years ago large mammals walked North America – the Mammoth, most famously, but also giant beavers, giant tree sloths, glyptodonts, and the American cheetah among them. By around 11,000 years ago they were all gone (38 genera, mostly mammals). Extinction is a natural part of the cycle of ecosystems, and no species lasts forever. But when paleontologists identify a pulse of extinctions, above the background rate, they call that an extinction event, and this definitely qualifies. Extinction events call out for answers – what was the cause?

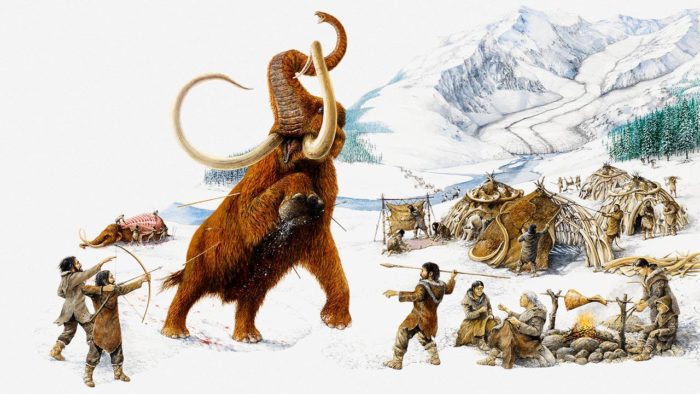

In the case of the North American megafauna extinction, there are two main hypotheses. The first is the overkill hypothesis – that the extinction coincides with the arrival of paleoindians on the continent, and that is not likely a coincidence. Generally speaking the arrival of humans into any ecosystem correlates with a pulse of extinctions. Perhaps the humans taking up residence in North America were big-game hunters, and the megafauna could not adapt quickly enough to this clever predator.

The second major hypothesis is that climatic change was the major cause. The last major glacial period lasted from 125,000 to 14,900 years ago, and then started the current interglacial period (the holocene) that we are in. However, this warming was interrupted in North American by the Younger Dryas, a cold snap that lasted from 12,900 to 10,600 years ago. The cause of this cold spell is also a controversy, with the two main hypotheses being a local comet impact vs the effects of major glacial melt on ocean currents. Either way, by the time the cold snap was over, the megafauna was gone.

What I find most interesting about this controversy is not the answer, but the controversy itself. It is a great example of how scientists work things out – they ask probing questions, and find clever ways to answer those questions. They don’t just spin narratives and stop there. The narratives are only a starting point, a hypothesis to be tested. Some of the questions raised include the following: Did the paleoindians actually hunt the megafauna? Is there any direct evidence for this? How well do the extinctions correlate with the climate change vs the arrival of the humans? Did megafauna survive previous interglacial periods, or is this typically associated with an extinction event?

At this point there are no definitive answers. This is due partly to the fact that the fossil record is still relatively scant. It is complete enough to get the broad brushstrokes, but not enough to draw tight correlations. What paleontologists due (other than look for more evidence) is to attempt statistical analysis of the evidence we do have, to wring the most information out of it possible. That is the focus of a new study, which applies a new statistical approach to this question.

The idea is to estimate the population sizes of humans and the megafauna throughout this period. This is done by essentially counting the amount of radiocarbon datable material, and using this as a marker for overall population size. It’s imperfect, but it is one window into this question. But the result is only as good as the statistical methods used to make the estimation. The new study uses a new statistical method that the authors claim is more accurate. To demonstrate this greater accuracy they compared it to simulations of known population sizes, and conclude that it is better than the older method. W. Christopher Carleton, the co-lead author on the study, explains:

“As a result, you can end up seeing trends in the data that don’t really exist, making this method rather unsuitable for capturing changes in past population levels. Using simulation studies where we know what the real patterns in the data are, we have been able to show that the new method does not have the same problems. As a result, our method is able to do a much better job capturing through-time changes in population levels using the radiocarbon record.”

Their results show a tight correlation between the megafauna population sizes and climatic change, favoring the climate hypothesis above the overkill hypothesis. This is certainly not the last word, to be sure, but it is one marker on that side of the scale. In 2015 scientists claimed to have the “final nail in the coffin” of this debate, claiming that correlation showed humans were the culprit. But now this is the answer to that evidence. Scientists also bring together multiple independent lines of evidence to address complex questions like this. If we, for example, find a butchering site where humans were processing dead mammoths, that would tip the scale in the other direction.

This is not to say there is no evidence of humans hunting megafauna. There is, for example, a site in Mexico with many mammoth remains. The site is likely a trap that mammoths fell into. Were they encouraged into the trap by humans? There is evidence of human manipulation of the remains, but does that mean they killed the mammoths or just scavenged them? There is also direct evidence of hunting, a flint spearpoint in a mammoth bone – in Poland. So European hunters were killing mammoths, which makes it plausible that North American humans were, but still there is no direct evidence in North America.

It is also possible that the answer to this question is – both. Climate change may have been stressing megafauna populations, and there is evidence of decline prior to the arrival of humans. But then humans may have added to their ecological stress, and provided the coup de grace. They may have done this by direct hunting, but they also may have done this by indirect methods such as changing the ecosystem is other ways.

There is a lot of scientific inference going on, which ensures that this debate is likely to continue for decades to come. No one piece of evidence can be definitive. The weight of evidence will continue to slowly pile up, and at some point it will likely be clear which side it is mostly on. It is also likely that the answer will turn out to be more nuanced and complicated. In any case, this is a fantastic scientific story (actually multiple layered scientific stories) playing out over a long period of time, and is wonderful to watch from the sidelines.