May 06 2019

Detecting Lies in the Brain

It’s fairly common knowledge at this point that the polygraph test for detecting who is lying is not reliable enough to be used practically. Here is a good summary by the American Psychological Association (APA). The bottom line is that the entire idea of a lie-detector is problematic for various reasons. First, the underlying premises have not really emerged from psychological research, and has not been validated by research. The idea is that people will display physiological signs of stress when they are making an effort to be deceptive, or when confronted with incriminating information. However, the relationship between physiological signs and mental stress is too complex to develop any test. There is no universal feature of lying that can be detected.

It’s fairly common knowledge at this point that the polygraph test for detecting who is lying is not reliable enough to be used practically. Here is a good summary by the American Psychological Association (APA). The bottom line is that the entire idea of a lie-detector is problematic for various reasons. First, the underlying premises have not really emerged from psychological research, and has not been validated by research. The idea is that people will display physiological signs of stress when they are making an effort to be deceptive, or when confronted with incriminating information. However, the relationship between physiological signs and mental stress is too complex to develop any test. There is no universal feature of lying that can be detected.

The polygraph uses two basic techniques. The first is the control question test (CQT) – you ask questions of the person being examined, control questions that do not relate to the crime in question, and relevant questions related to the crime. The idea is that they will react more to the relevant than the control questions. The other method, the guilty knowledge test (GKT) is similar – mentioning random items along with one directly related to the crime may reveal guilty knowledge that only the perpetrator should know.

The idea sounds compelling, and it does work in that using these techniques results in a slight statistical advantage in determining who is lying and who isn’t. However, a small statistical advantage is all but worthless in practical application. There are too many false positives and false negatives to be useful. For any individual suspect, at the end of the test you still don’t know if they are lying or not.

Part of the problem is that people are complex and variable. Not everyone responds the same way to stress, or to the situations provoked in the testing. But the problem is worsened by the existence of effective mental countermeasures. There are two basic countermeasures that have been shown to be effective – lowering further the statistical effect of the polygraph. The first is to assign mental significance to control items or questions, thereby reacting similarly to the control and the relevant items. The second is to create mental distance to all the items, including the relevant ones. Focus on something else – the sound of the words, their precise dictionary meaning, or imagine a famous character saying them. If the statements are in writing, you can focus on the color of the ink, the font, or other superficial aspects.

These countermeasure work. They successfully blur any difference between control and relevant items.

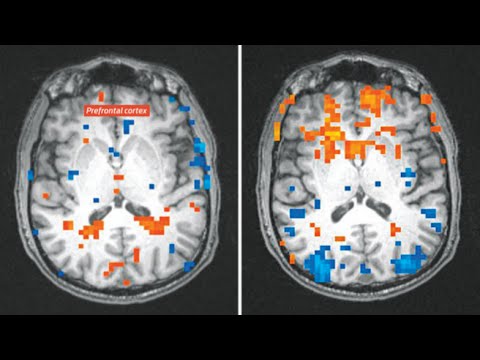

A new era of lie detection, however, is starting with research into the use of functional MRI scanning (fMRI) to look directly at brain function to detect who is lying and who isn’t. The idea is very compelling – you can’t hide the activity in your brain. Even if you are using countermeasures, the imaging will show the extra effort of the countermeasures (in theory). A recent study examines these ideas. They used two different fMRI techniques, region of interest imaging and whole-brain imaging. They studied 20 subjects with no prior training and gave them quick instructions on the two mental countermeasures I described above. They were then tested with the guilty knowledge test method.

For the regional imaging, the study showed, first, that the technique “works” is that it can statistically separate control items from guilty items (in this case the subjects were given a number to keep secret, then shown several numbers including the secret one). While more effective than polygraph, the results are still not good enough to use as a method for practically telling who is innocent and who is guilty. Further, the countermeasures reduced the effectiveness of the analysis by 20%. Keep in mind, these are untrained random subjects simply told how to do the countermeasures.

For whole brain analysis the countermeasures were not statistically significantly effective, but this is probably because the baseline effectiveness of this analysis was very low to begin with (so there was not much room for an effect). So when you combine countermeasures with either analysis technique, neither works sufficiently to be of practical use.

The question now is whether fMRI or any similar imaging technique will ever be good enough to reliably detect deception. It is an interesting theoretical question. One the one hand, as our functional imaging techniques get better, with greater precision and improved analysis, such detection techniques should similarly improve. Using AI-algorithms to learn how to detect deception seems promising.

On the other hand, there is inherent chaos in mental states – a lot of noise hiding any relevant signals. Further, there may be no practical limit of effective mental countermeasures. Someone might be able to train themselves to think exactly like they are innocent, or at least to obscure any guilty signal. This might be similar to really good actors. On some level, they are not pretending to be the character they are playing, but mentally must become the character. They have to fake emotions sufficiently well to fool an audience of humans which evolution has fine tuned to be expert detectors of emotion. They learn techniques to help them do this, to produce genuine emotion on command. In other words – fooling any lie-detection technique seems to be a skill that can be mastered.

Still, if we keep extrapolating into the future of this technology, we may get to the point that our imaging is so precise it can pull actual memories out of your brain. At that point, I don’t know what an effective countermeasure might be. But this really goes beyond lie detection (detecting your reaction to information, or what is going on in your brain when you are making a statement) vs just reading information in your brain, no matter what you are thinking about at the moment. We might conclude ultimately that lie detection will never work well enough because of the inherent nature of mental states and the effectiveness of countermeasures. However, reconstructing information from the brain may at some point become accurate enough to serve as a record of your past deeds. This is more like a brain camera than lie detection, but can serve the same purpose.

The implications on this technology for privacy is another question, but one we may have to answer at some point.