Mar 08 2016

What Causes Overconfidence?

People are overconfident. That is a clear signal in psychological research that is reliably replicated. At this point it can be taken as a given. The brain is a complex machine, however, and any one factor such as confidence interacts in multiple and complex ways with many other mental factors.

People are overconfident. That is a clear signal in psychological research that is reliably replicated. At this point it can be taken as a given. The brain is a complex machine, however, and any one factor such as confidence interacts in multiple and complex ways with many other mental factors.

Questions that have not been fully addressed include the possible causes and effects of overconfidence. Dunning and Kruger famously isolated one factor – overconfidence (the difference between self-assessment and actual performance) increases as performance decreases. This effect (called the Dunning-Kruger effect) is offered as one explanation for what causes overconfidence – the competence to assess one’s own competence.

A new series of studies looks at another factor that may influence overconfidence, ideas about the nature of intelligence itself. Joyce Ehrlinger and her colleagues performed three studies looking at the effect of two theories of intelligence on overconfidence. The two theories in question are the notion that intelligence is largely fixed (called the entity theory) vs the idea that intelligence is highly malleable (called the incremental theory).

Ehrlinger hypothesized that entity theorists would be more overconfident than incremental theorists. In the first of three studies, this one involving 53 university students, she found exactly that. Subjects were asked questions to assess their attitudes toward intelligence, with statements such as, “You have a certain amount of intelligence, and you can’t really do much to change it” and “You can always substantially change how intelligent you are.” They had to rank such statements on a scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

Subjects completed a test of moderate difficulty and were then asked to guess how they did compared to others, from 0%-99%. They found that those subjects who agreed more that intelligence is fixed had an average self assessment of 76% while those who felt that intelligence is malleable had an average self assessment of 55% (by definition the true average was 50%).

So, there was a general overconfidence effect (the technical term for which is overplacement), but it was disproportionately present in the subgroup of subjects who believe that intelligence is fixed.

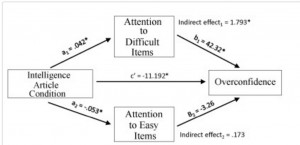

The next two studies addressed the question of whether or not having a fixed view of intelligence causes overconfidence and if so how. In order to make a causal inference you need to manipulate the variable, not just associate it. So in the second study the researchers did just that – they gave subjects one of two articles to read (saying it was a test of reading comprehension). One article discussed scientific evidence that intelligence is fixed, while the other article discussed scientific evidence that intelligence is malleable.

The researchers were interested in two variables, the degree of overconfidence and the amount of time subjects spent on easy questions vs difficult questions. The subjects were taking the test on computer, allowing them freedom to spend as much time on each question as they wished, and the program tracked that time.

The results confirmed what the researchers suspected, that the subjects exposed to the entity article had higher overconfidence than the incremental article, 68% vs 59%. This difference is not as big as when subjects self-sorted into these two groups but that makes sense. In the first experiment the researchers were looking at the subjects’ long held views of intelligence. What is remarkable is that in the second experiment these views were so easily manipulated by reading a single article (at least temporarily).

Further, the researchers found that those in the entity group spent more time on the easy questions and less time on the difficult questions than the incremental group. The researchers hypothesized from this that focusing on the easy tasks reinforced overconfidence, while spending time on difficult questions was humbling. They explored that question in the third study.

In this study they forced subjects to spend more time focusing on the easy or the difficult questions, by given them either time-consuming or rapid secondary tasks. In the attention-to-ease group, those who also had an entity theory of intelligence were more overconfident than their incremental peers, 67% vs 55%. In the attention-to-difficulty group, there was no statistical difference, 58% vs 61%.

What does all this mean? First, I have to point out that this is one moderate-sized study. The results are reasonably robust, but will need to be replicated before we can be confident in the results. However, taking them at face value:

- The results are yet another confirmation of an overall overconfidence effect.

- The results suggest that overconfidence is stronger among those who believe that intelligence is fixed, and much smaller among those who believe that intelligence is malleable

- The correlation between beliefs about intelligence and overconfidence seem to be at least partly mediated by attention to easy vs difficult tasks.

This sounds like a type of confirmation bias. We reinforce beliefs about our own competence by focusing our attention on easy tasks that make us feel competent, and glossing over difficult tasks that would have a humbling effect on our self-assessment.

It is very interesting, however, that our beliefs about the nature of intelligence seem to be the determining factor here. Having a fatalistic view, that our intelligence is fixed and there is not much you can do about it, motivates us to reinforce our own sense of overconfidence. The exact relationship there needs to be further explored.

One hypothesis that occurs to me is that people who think there is nothing they can do about their level of intelligence are more highly motivated to feel that their intelligence is already above average, and they seek out confirmation of that belief.

Those who believe intelligence is malleable are more comfortable with also thinking that they are average or a little above average (they are still overconfident, but not by much) because they also feel there is something they can do about it. It can motivate them to focus on challenging tasks in order to become more intelligent, which in turn moderates their overconfidence.

This jibes with another trend in psychological research, the notion that attitudes can affect performance. Those who believe they are lucky actually do have better outcomes, because they are more willing to take advantage of opportunities. In this case those who think they can improve their intelligence are more willing to work hard to do so.

In fact the authors of the current study point to prior research which shows that having a malleable view of intelligence is associated with better school performance. They argue that we should therefore teach children incremental views of intelligence as a motivational strategy.

This seems reasonable, but I do think that this approach generally can be taken too far. The “you can do anything” motivational speaking can become counterproductive if it is unrealistic. I suspect there is a sweet spot, a balance between believing that hard work is effective and will pay off, while having realistic and achievable goals.

Another way to view the results of this study is that everyone has competing motivations with different net results. We all want to feel competent, and want to feel that we can improve ourselves, but also fear failure and find the prospect of working hard daunting. The question is – which is a stronger motivation.

In my experience (and this is now just my opinion) people tend to fall into various stable conditions. There are those who think that working hard is pointless, so why try. They may feel that a goal or a task is simply beyond their abilities, and so they are relieved from the burden of feeling that they should make an effort.

Others feels that they have the ability to benefit from hard work, and so that work is justified by the results. They are motivated to believe in the possibility of change in order to justify their hard work.

Further, the same person can have both views simultaneously about different things.

Conclusion

It’s interesting to think about all of the competing thoughts and emotions leading to the end result of behavior in people. With this series of studies we may have one more piece of this complex puzzle – people are overconfident, especially if they think intelligence is fixed, partly because they focus on easy rather than challenging tasks.

This kind of knowledge allows us to get outside ourselves, to manipulate the rules of the game rather than just be subject to them.

People certainly can improve their skills and knowledge. Talent counts for something, but hard work also counts. The research so far suggests that most people can master most tasks, it just may be a lot harder for some people and a lot easier for others.

We each have to decide where to spend our time and effort, and as with many things it is probably best to make rational and evidence-based decisions rather than letting emotions make decisions for us.