Nov 06 2014

Lessons from Dunning-Kruger

In 1999 psychologist David Dunning and his graduate student Justin Kruger published a paper in which they describe what has come to be known (appropriately) as the Dunning-Kruger effect. In a recent article discussing his now famous paper, Dunning summarizes the effect as:

In 1999 psychologist David Dunning and his graduate student Justin Kruger published a paper in which they describe what has come to be known (appropriately) as the Dunning-Kruger effect. In a recent article discussing his now famous paper, Dunning summarizes the effect as:

“…incompetent people do not recognize—scratch that, cannot recognize—just how incompetent they are,”

He further explains:

“What’s curious is that, in many cases, incompetence does not leave people disoriented, perplexed, or cautious. Instead, the incompetent are often blessed with an inappropriate confidence, buoyed by something that feels to them like knowledge.”

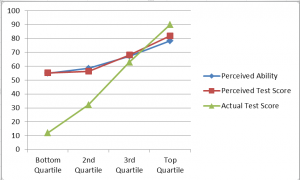

As you can see in the chart above, the most competent individuals tend to underestimate their relative ability a little, but for most people (the bottom 75%) they increasingly overestimate their ability, and everyone thinks they are above average. I sometimes hear the effect incorrectly described as, “the more incompetent you are, the more knowledgeable you think you are.” As you can see, self-estimates do decrease with decreasing knowledge, but the gap between performance and self-assessment increase as you decrease in performance.

The Dunning-Kruger effect has now been documented in many studies involving many areas. There are several possible causes of the effect. One is simple ego – no one wants to think of themselves as below average, so they inflate their self-assessment. People also have an easier time recognizing ignorance in others than in themselves, and this will create the illusion that they are above average, even when they are in the single digits of percentile.

The core of the effect, however, seems to be what Dunning describes – ignorance carries with it the inability to accurately assess one’s own ignorance. Dunning also points out something that rings true to this veteran skeptic:

An ignorant mind is precisely not a spotless, empty vessel, but one that’s filled with the clutter of irrelevant or misleading life experiences, theories, facts, intuitions, strategies, algorithms, heuristics, metaphors, and hunches that regrettably have the look and feel of useful and accurate knowledge.

This accurately describes the people I confront daily with unscientific or unsupported beliefs. Just read the comments on the SGU’s Facebook page and you will quickly be subject to the full force of Dunning-Kruger.

What I think Dunning is describing above, a conclusion with which I completely agree, are the various components of confirmation bias. As we try to make sense of the world we work with our existing knowledge and paradigms, we formulate ideas and then systematically seek out information that confirms those ideas. We dismiss contrary information as exceptions. We interpret ambiguous experiences in line with our theories. We remember and then our memories tweak any experience that seems to confirm what we believe.

In the end we are left with a powerful sense of knowledge – false knowledge. Confirmation bias leads to a high level of confidence, we feel we are right in our gut. And when confronted with someone saying we are wrong, or promoting an alternate view, some people become hostile.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is not just a curiosity of psychology, it touches on a critical aspect of the default mode of human thought, and a major flaw in our thinking. It also applies to everyone – we are all at various places on that curve with respect to different areas of knowledge. You may be an expert in some things, and competent in others, but will also be toward the bottom of the curve in some areas of knowledge.

Admit it – probably up to this point in this article you were imagining yourself in the upper half of that curve, and inwardly smirking at the poor rubes in the bottom half. But we are all in the bottom half some of the time. The Dunning-Kruger effect does not just apply to other people – it applies to everyone.

This pattern, however, is just the default-mode, it is not destiny. Part of skeptical philosophy, metacognition, and critical thinking is the recognition that we all suffer from powerful and subtle cognitive biases. We have to both recognize them and make a conscious effort to work against them, realizing that this is an endless process.

Part of the way to do this is to systematically doubt ourselves. We need to substitute a logical and scientific process for the one Dunning describes above. We need to cultivate what I call “neuropsychological humility.”

As an illuminating example, I am involved in medical student and resident education. The Dunning-Kruger effect is in clear view in this context as well, but with some interesting differences. At a recent review, for example, every new resident felt that they were below average for their class. Being thrown into a profession where your knowledge is constantly being tested and evaluated, partly because knowledge is being directly translated into specific decisions, appears to have a humbling effect (which is good). It also helps that your mentors have years or decades more experience than you – this can produce a rather stark mirror.

Still, we see Dunning-Kruger in effect. The gap between self-assessment and actual ability grows toward the lower end of the ability scale.

However, medical education is a special case because self-assessment is a skill we specifically teach and assess. It is critically important for physicians to have a fairly clear understanding of their own knowledge and skills. We specifically try to give students an appreciation for what they do not know, and the seemingly bottomless pit of medical information is in constant display.

I remember as a resident seeing a two volume massive tome just on muscle disease and thinking, holy crap, that is how much I don’t know about muscle disease. There are also equal volumes on every other tiny aspect of medicine. It can be overwhelming.

As students and residents go through their training, we also keep moving that carrot forward. As they get more confident in their basic skills we have to make sure they don’t get cocky. I talk to my residents specifically about the difference between competence, expertise, and mastery.

One specific lesson I try to drive home as often as possible, both in the context of medical education and in general, is this: Think about some area in which you have a great deal of knowledge, in the expert to mastery level (or maybe just a special interest with above average knowledge). Now, think about how much the average person knows about your area of specialty. Not only do they know comparatively very little, they likely have no idea how little they know, and how much specialized knowledge even exists.

Here comes the critical part – now realize that you are as ignorant as the average person is every other area of knowledge in which you are not expert.

Conclusion

The Dunning-Kruger effect is not just about dumb people not realizing how dumb they are. It is about basic human psychology and cognitive biases. Dunning-Kruger applies to everyone.

The solution is critical thinking, applying a process of logic and empiricism, and humility – in other words, scientific skepticism.

In addition to the various aspects of critical thinking, self-assessment is a skill we can strive to specifically develop. But a good rule of thumb is to err on the side of humility. If you assume you know relatively less than you think you do, and that there is more knowledge than of what you are aware, you will usually be correct.