Aug 13 2024

Framing and Global Warming

When we talk publicly about the effects of human activity on the climate should we refer to “global warming”, “climate change”, the “climate crisis” or to “climate justice”? Perhaps we should also be more technical and say specifically, “anthropogenic climate change”. This kind of question is often referred to as “framing”, meaning that we need to be thoughtful about how we frame topics for science communication and open discussion.

When we talk publicly about the effects of human activity on the climate should we refer to “global warming”, “climate change”, the “climate crisis” or to “climate justice”? Perhaps we should also be more technical and say specifically, “anthropogenic climate change”. This kind of question is often referred to as “framing”, meaning that we need to be thoughtful about how we frame topics for science communication and open discussion.

I remember about two decades ago when the concept of “framing” was really introduced into the skeptical community. There was a lot of pushback, because the practice was considered to be deceptive, and more aligned with political persuasion than science communication. This criticism was unfounded, in my opinion, largely because it is naive. It assumes, falsely, that you can communicate without framing. In reality you are framing your messages whether you know it or not, so you might as well be conscious and thoughtful about it.

To get into more detail, what is meant by framing is the overall approach to a topic in terms of major perspectives and considerations. For example, we can frame a discussion on GMOs as purely a scientific question – what does the evidence say about the risks and benefits of genetic engineering technology? We can also frame the topic as one of regulation – how should governments regulate GMOs? Or we can focus on corporate behavior and power. Often, the explicit framing I take on this blog, the framing focusses on critical thinking, pseudoscience, and conspiracy theories. How do we think logically and make sense of all the claims and information?

Often framing is deliberate and manipulative, even deceptive. This is common in politics, which is why there can be a negative reaction to the concept. Do we talk about gun control, gun regulation, or gun safety? Should we frame the inheritance tax as a “death tax”, or hospital ethics committees as “death panels”? Deceptive framing can “rig the game” by trying to bake in unwarranted assumptions right at the beginning of a discussion – assuming your conclusion.

But just because framing can be abused does not mean it is always a bad practice or something to be avoided. Again – if you are having a discussion, you are using framing, whether you know it or not. The real goal is to properly and fairly frame a discussion or debate – don’t make unwarranted assumptions, don’t use overly emotional or biased terms, don’t exclude legitimate concerns (by using a narrow framing), and don’t be unfair to any one side.

Sometimes different framings are equally valid, but may affect how a message is perceived. There is a vast literature on this. For example, if a surgeon tells you that a surgical procedure they are recommending has a 98% survival rate you are more likely to accept the procedure than if they say it has a 2% fatality rate. This is the exact same information, just framed differently.

You may be thinking -well, just say both so as not to bias the information. That may be reasonable in some cases, but that is also just another aspect of framing – how much information do you give, and in how many different formats? In a technical journal, giving maximally technical and precise information, from multiple perspectives, is likely appropriate. Give the P-value, and the number needed to treat, the effect size, and the Bayesian analysis. But is this the best way to communicate that information to a patient facing a life-and-death decision? Overwhelming the target with highly technical information is not always the most effective method of communication. Anything less that that, however, means giving a simplified approximation, which requires decisions about which information to include, and in what format. This is framing. There is also a continuum from giving a bottom-line, single point framing all the way to maximal detail – and that is another decision that should be conscious and deliberate.

What is the best or most appropriate framing depends on context. Who is your audience, and what exactly are you trying to convey? Is this a public health message meant to have a maximal impact on behavior? Or are you trying get people to think more deeply and with more nuance about a complex topic?

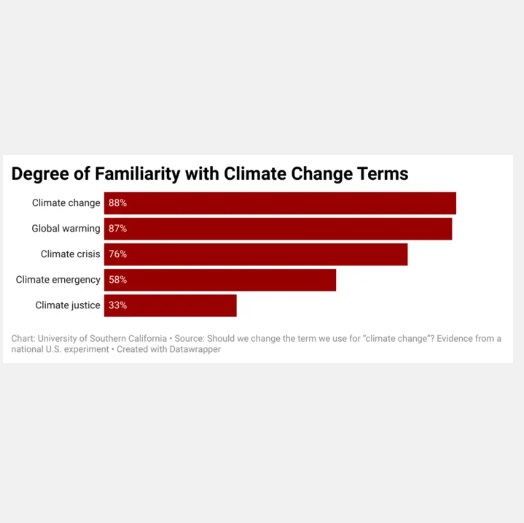

Bringing this back to climate change, a recent study looked at different terms to use when referring to the topic – global warming, climate change, climate crisis, climate emergency, and climate justice. They found that people were more familiar with the terms global warming and climate change (about 88%), less so to crisis or emergency (76 and 58%), and least to climate justice (33%). Further, they were also less likely to express concern about these topics, in proportion to their familiarity. They concluded that familiarity with the terms used in framing a topic affects how the receiver responds to the messaging.

Of course there are other conf0unding variables as well. For example, it is possible that when using terms like “crisis” and “emergency” people may feel these terms are biased therefore the messenger is biased. They may react to emotional language defensively, on the assumption (usually a good one) that they are being manipulated. Also, the term “justice” has a lot of social baggage, as it has often been framed negatively as a zero-sum game – justice for one group comes at the expense of another group. But it does seem that familiarity is a consistent factor as well.

These are all good things to consider when framing a message. The authors conclude that we should stick with climate change and global warming, because people are most familiar with these terms. However, you could just as easily argue that we should spend capital on communicating the concept of climate justice to make people more familiar with the term. They don’t directly compare these strategies. This is a common debate we have within skepticism and science communication – do we use familiar terms, or market new terms that have a better framing? This depends on the details – sometimes the familiar terms are negatively framed and need to change. But sometimes we need to live with the familiar terms. Either way, decisions should be appropriate and strategic, not made thoughtlessly and by default.