Sep 04 2025

Charting The Brain’s Decision-Making

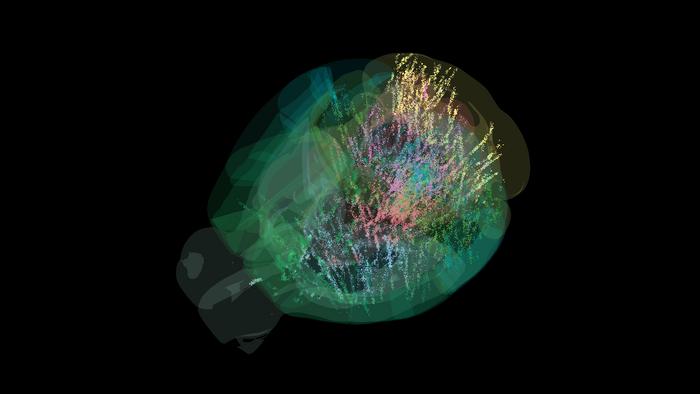

Researchers have just presented the results of a collaboration among 22 neuroscience labs mapping the activity of the mouse brain down to the individual cell. The goal was to see brain activity during decision-making. Here is a summary of their findings:

Researchers have just presented the results of a collaboration among 22 neuroscience labs mapping the activity of the mouse brain down to the individual cell. The goal was to see brain activity during decision-making. Here is a summary of their findings:

“Representations of visual stimuli transiently appeared in classical visual areas after stimulus onset and then spread to ramp-like activity in a collection of midbrain and hindbrain regions that also encoded choices. Neural responses correlated with impending motor action almost everywhere in the brain. Responses to reward delivery and consumption were also widespread. This publicly available dataset represents a resource for understanding how computations distributed across and within brain areas drive behaviour.”

Essentially, activity in the brain correlating with a specific decision-making task was more widely distributed in the mouse brain than they had previously suspected. But more specifically, the key question is – how does such widely distributed brain activity lead to coherent behavior. The entire set of data is now publicly available, so other researchers can access it to ask further research questions. Here is the specific behavior they studied:

“Mice sat in front of a screen that intermittently displayed a black-and-white striped circle for a brief amount of time on either the left or right side. A mouse could earn a sip of sugar water if they quickly moved the circle toward the center of the screen by operating a tiny steering wheel in the same direction, often doing so within one second.”

Further, the mice learned the task, and were able to guess which side they needed to steer towards even when the circle was very dim based on their past experience. This enabled the researchers to study anticipation and planning. They were also able to vary specific task details to see how the change affected brain function. Any they recorded the activity of single neurons to see how their activity was predicted by the specific tasks.

The primary outcome of the research was to create the dataset for further study. So many of the findings that will eventually come out of this data are yet to be found. But we can make some preliminary observations. As I stated above, tasks involving sensory input, decision-making, and motor activity are widely distributed throughout the mouse brain. This activity involves a great deal of feedback, or crosstalk across many different regions. What implications does this have for our understanding of brain function?

I think this moves us in the direction of understanding brain function more in terms of complex networks rather than specific modules or circuits carrying out specific tasks. This is not to say there aren’t specific circuits – we know that there are, and many have been mapped out. But any task or function results from many circuits dynamically networking together, in a constant feedback loop of neural activity. This makes reverse-engineering brain activity, even in a mouse, extremely complex. Any simple schematic of brain circuits is not going to capture what is really going on.

Another observation to come out of this data is that sensory and motor areas are more involved in decision-making than was previously suspected. The motor cortex is not just the final destination of activity, where decisions are translated into action. They are involved in planning and decision making also. It remains to be seen what the ultimate implications of this observation are, but it is interesting from the perspective of the notion of embodied cognition.

Embodied cognition is the idea that our thinking is inextricably tied to our physical embodiment. We are not a brain in a jar – we are part of a physical body, and our brains map to and are connected to that body. They are one system. We interact with the world largely physically, and therefore we think largely physically. Even our abstract ideas are rooted in physical metaphors. This is why an argument can be “weak”, and a behavior might be “beneath” you, and we equate morality to physical disgust. A “big” idea is not physically big, but that is how we conceptualize it.

Embodied cognition might go even further, however. Our physical senses and the brain circuits involved in movement might also be involved in thinking. This make sense – we plan our movements with the pre-motor cortex, for example.

If we look at this question evolutionarily, what this may mean is that our higher and more abstract cognitive functions are evolutionary extrapolations or extensions of our physical functions. Mammalian brains first evolved to receive and interpret sensory information and to control our movements. Our ability to perceive and to move evolved greater and greater complexity, while emotional centers also evolved to drive basic behaviors, like hunger, fear, and mating. This all had to function as a coherent system, so circuits evolved with more and more integration of sensory and motor pathways, including a subjective experience of embodiment, ownership, and control. Eventually more abstract cognitive functions became possible, including social interaction, more sophisticated planning and anticipation, etc. But most things in evolution do not come from nowhere – they are extensions of existing functions. So it makes sense from this perspective that abstract cognition evolved out of physical cognition, and these roots run deep.

It is also interesting to think about the implications of this research in the context of AI. First, I suspect that AI will help us make sense of the massive amount of data and complexity we are seeing with mouse brain activity. Imagine when we attempt this level of detail with a human brain and human decision-making. Further, we can use this information to construct (by whatever methods) AI that more and more mimics the functioning of a human brain. These projects will likely feed off each other – using AI to understand the brain then using the resulting information to design AI. It’s possible that something like this will lead to an AI that replicates the functioning of a human brain.

But here is a question – if we do take this research to its ultimate conclusion, will that AI need to be incorporated into a physical body in order to fully replicate a human brain? Will a virtual body suffice? But either way – will it need sensory input and motor output in order to function like a human brain? What would a disembodied human brain or simulation be like? Would it be stable?

Whatever the result, it will be fascinating to find out. I think the one safe prediction is that we still have many surprises in store.