Mar 21 2023

Unifying Cognitive Biases

Are you familiar with the “lumper vs splitter” debate? This refers to any situation in which there is some controversy over exactly how to categorize complex phenomena, specifically whether or not to favor the fewest categories based on similarities, or the greatest number of categories based on every difference. For example, in medicine we need to divide the world of diseases into specific entities. Some diseases are very specific, but many are highly variable. For the variable diseases do we lump every type into a single disease category, or do we split them into different disease types? Lumping is clean but can gloss-over important details. Splitting endeavors to capture all detail, but can create a categorical mess.

Are you familiar with the “lumper vs splitter” debate? This refers to any situation in which there is some controversy over exactly how to categorize complex phenomena, specifically whether or not to favor the fewest categories based on similarities, or the greatest number of categories based on every difference. For example, in medicine we need to divide the world of diseases into specific entities. Some diseases are very specific, but many are highly variable. For the variable diseases do we lump every type into a single disease category, or do we split them into different disease types? Lumping is clean but can gloss-over important details. Splitting endeavors to capture all detail, but can create a categorical mess.

As is often the case, an optimal approach likely combines both strategies, trying to leverage the advantages of each. Therefore we often have disease headers with subtypes below to capture more detail. But even there the debate does not end – how far do we go splitting out subtypes of subtypes?

The debate also happens when we try to categorize ideas, not just things. Logical fallacies are a great example. You may hear of very specific logical fallacies, such as the “argument ad Hitlerum”, which is an attempt to refute an argument by tying it somehow to something Hitler did, said, or believed. But really this is just a specific instance of a “poisoning the well” logical fallacy. Does it really deserve its own name? But it’s so common it may be worth pointing out as a specific case. In my opinion, whatever system is most useful is the one we should use, and in many cases that’s the one that facilitates understanding. Knowing how different logical fallacies are related helps us truly understand them, rather than just memorize them.

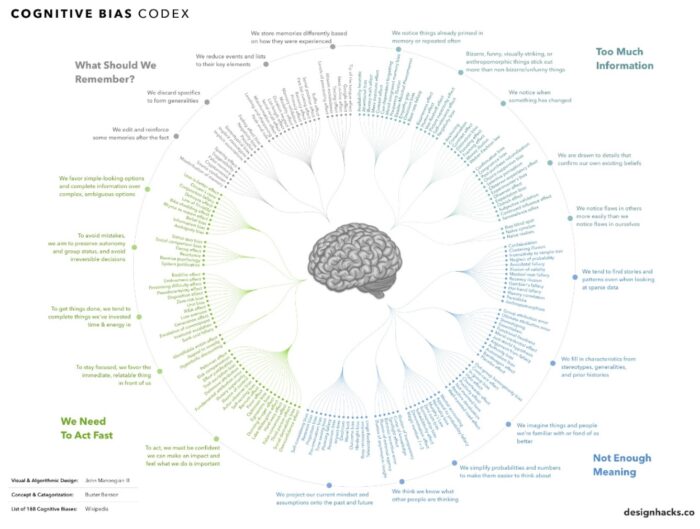

A recent paper enters the “lumper vs splitter” fray with respect to cognitive biases. They do not frame their proposal in these terms, but it’s the same idea. The paper is – Toward Parsimony in Bias Research: A Proposed Common Framework of Belief-Consistent Information Processing for a Set of Biases. The idea of parsimony is to use to be economical or frugal, which often is used to apply to money but also applies to ideas and labels. They are saying that we should attempt to lump different specific cognitive biases into categories that represent underlying unifying cognitive processes.

The headline in the New York Post reads:

The headline in the New York Post reads:  Often, contentious political and social questions have a scientific question in the middle of them. Resolving the scientific question will not always resolve the political ones, but at least it can properly inform the debate. The recent overturning of Roe v Wade has supercharged the debate about when human life begins. It may seem, then, that what science has to say about this question is important to the debate. But it may be less useful than it at first appears.

Often, contentious political and social questions have a scientific question in the middle of them. Resolving the scientific question will not always resolve the political ones, but at least it can properly inform the debate. The recent overturning of Roe v Wade has supercharged the debate about when human life begins. It may seem, then, that what science has to say about this question is important to the debate. But it may be less useful than it at first appears. Humans overall suck at logic. We have the capacity for logic, but it is only one of many algorithms running in our brains, and often gets lost in the noise. Further, we have many intuitions, biases, and cognitive flaws that degrade our ability to think logically. Fortunately, however, we also have the ability for metacognition, the ability to think about our own thinking. We can therefore learn logic and how to think more clearly, filtering out the biases and flaws. It is impossible to do this perfectly, so it is best to think of metacognition as a life-long project of incremental self-improvement. Further, our biases can be so powerful, that when we learn how to think about thinking we often just make our logical fallacies more and more subtle, rather than eliminating them entirely.

Humans overall suck at logic. We have the capacity for logic, but it is only one of many algorithms running in our brains, and often gets lost in the noise. Further, we have many intuitions, biases, and cognitive flaws that degrade our ability to think logically. Fortunately, however, we also have the ability for metacognition, the ability to think about our own thinking. We can therefore learn logic and how to think more clearly, filtering out the biases and flaws. It is impossible to do this perfectly, so it is best to think of metacognition as a life-long project of incremental self-improvement. Further, our biases can be so powerful, that when we learn how to think about thinking we often just make our logical fallacies more and more subtle, rather than eliminating them entirely. Spanish company Nueva Pescanova is close to

Spanish company Nueva Pescanova is close to  If someone gets seriously ill from COVID, to the point that they need to be hospitalized and even placed in ICU, and they were unvaccinated, how much should we blame them for their illness? This question can have practical implications, if we base decisions on allocating limited resources and insurance coverage of vaccine status. I

If someone gets seriously ill from COVID, to the point that they need to be hospitalized and even placed in ICU, and they were unvaccinated, how much should we blame them for their illness? This question can have practical implications, if we base decisions on allocating limited resources and insurance coverage of vaccine status. I  What do economics, biological evolution, and democracy have in common? They are all complex adaptive systems. This realization reflects one of the core strengths of a diverse intellectual background – there are meaningful commonalities underlying different systems and areas of knowledge. In fact, science and academia themselves are complex adaptive systems that benefit from diversity of knowledge and perspective. All such systems benefit from diversity, and suffer when that diversity is narrowed, possibly even fatally.

What do economics, biological evolution, and democracy have in common? They are all complex adaptive systems. This realization reflects one of the core strengths of a diverse intellectual background – there are meaningful commonalities underlying different systems and areas of knowledge. In fact, science and academia themselves are complex adaptive systems that benefit from diversity of knowledge and perspective. All such systems benefit from diversity, and suffer when that diversity is narrowed, possibly even fatally. In 2017 astronomers spotted a very unusual object approaching Earth. What was most unusual about it was that it was on a trajectory that would take it out of the solar system. Given its path it could only have come from outside the solar system – our first ever discovered extrasolar visitor,

In 2017 astronomers spotted a very unusual object approaching Earth. What was most unusual about it was that it was on a trajectory that would take it out of the solar system. Given its path it could only have come from outside the solar system – our first ever discovered extrasolar visitor,  I interviewed philosopher Philip Goff

I interviewed philosopher Philip Goff