Mar 24 2020

Body Ownership Illusion

A new study offers a small advance in our understanding of the body ownership illusion, but it is a good opportunity to review this cool and important neurological phenomenon. It also has practical implications. The body ownership illusion is the subjective sense that you occupy or own your body and its parts. There is also a separate phenomenon that gives you the subjective sense that you control your body parts.

offers a small advance in our understanding of the body ownership illusion, but it is a good opportunity to review this cool and important neurological phenomenon. It also has practical implications. The body ownership illusion is the subjective sense that you occupy or own your body and its parts. There is also a separate phenomenon that gives you the subjective sense that you control your body parts.

What I find extremely interesting about these phenomena is that we initially didn’t know they needed to exist. People don’t generally wonder what creates the sense that they own and control their own bodies. It’s not even a question people think to ask (unless they are somehow involved in neuroscience). At first it may seem obvious – we are our bodies, and we do control our bodies, so why shouldn’t we have that sense? But like everything you experience and feel, this is not a passive or automatic sensation. It is an active construction of your brain. There are dedicated circuits in the brain whose specific function is to create these sensations.

As with most neurological phenomena we first suspected their existence by encountering patients who have suffered brain damage (like from a stroke) and therefore have a lack of some subset of these functions. For example, there is alien-hand syndrome. This is the sense that a body part is acting “on it’s own” without your conscious control. There are also cases that demonstrate the separation of body parts from the sense that we own those body parts. Phantom limbs, for example, occur when a limb is removed but the brain circuitry that creates the sense of ownership of the limb is still there. There can even be supernumerary phantom limbs – an illusion of an extra limb that was never there. This can happen when a stroke paralyzes a limb but spares the circuitry that creates the sense of ownership. There are also cases of the apparent opposite – when a limb is present and functioning, but the person has the uncomfortable sense that it does not belong to them. We also have evidence from certain drug-induced and other states of feeling entirely separated from our bodies.

We have a partial understanding of how our brains create these sensations. They all involve circuits that compare two or more inputs. When they are synchronous we have the subjective sense of ownership or control. For the sense of control the circuits compare our intention to move and our actual movements. When they match, we feel we have control. For ownership the primary circuit involves “visual-motor synchronization” or visual-sensory synchronization. If what we see of ourselves matches what we feel, that synchronization produces the sense of ownership. Obviously, we don’t immediately have an out-of-body experience when we close our eyes. There are other sensory inputs that act redundantly – proprioception, vestibular function, tactile sensation, and muscle feedback. It’s a robust system, which is why the illusion rarely breaks in day-to-day life. You have to disrupt the main parts of the brain producing this sensation with drugs, oxygen deprivation, or something else.

Is it proper to call this sensation an “illusion”? Sort of. It is not an illusion in that it is real, but it is an illusion in that it is a constructed subjective experience. Using optical illusions as an example of why this is an important point – when we see something that is clearly not real, because it is tricking our visual construction, we call that an illusion. But the process creating that illusion is identical to the process that creates our normal vision. Also, neither are accurate – they are approximations of a tiny slice of reality the algorithms in our brains determine to be most important at that moment. All visual perception is a constructed illusion, it’s just that at some times the illusion breaks.

The same is true of the body ownership illusion – we can break it, and we call that the illusion. But this is no different than the normal sensation. To be clear, I don’t care about the semantics. I just want to drive home the nature of the neurological phenomena.

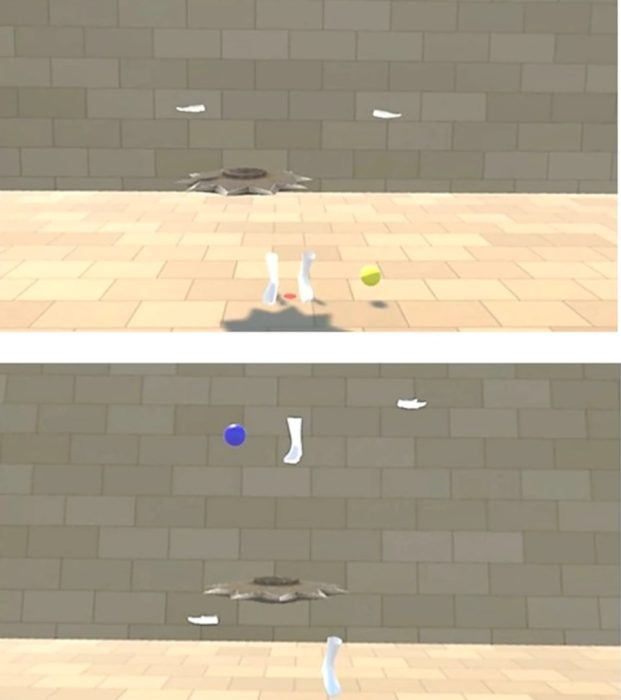

Experimentally, the body ownership illusion is created by crafting a false synchronization between what a subject sees and what they feel. The simplest version of this is to have them sit at a table and place one arm above and one arm below the table. The arm below is then blocked from vision by a screen or blanket. A fake arm is then placed above the table where the real arm would be. If the fake arm is touched at the same time and place as the real arm, this visual sensory synchronization is enough in many subjects to feel as if the fake arm is theirs – they own it. We can take this a step further and use VR goggles to see an entire body avatar, and then synchronize (which can simply be done by having the avatar be a live video of the subject themselves) the avatar with the movements and sensations of the subject. Body ownership can then shift to the avatar.

In the first situation we have body part ownership, and in the second we have whole body ownership. The question is – is the whole the sum of the parts or is there an additional circuit for the whole body that is more than just the sum of the body parts? That is the question the current study sought to address. In this study the researchers simulated only the hands and feet, and used sensory synchronization to create the ownership illusion. They then compared scrambled vs unscrambled body parts. So in one condition the hands and feet were simulated in their proper orientation. This created the illusion of ownership over each of the hands and feet but also of the whole body. In the second condition the hands and feet were not in their proper orientation. This still created the illusion of ownership over each synchronized body part, but not an illusion of whole body ownership.

This suggests that there is an additional function for whole-body ownership, perhaps aligned with our internal model of our own bodies. When this internal “homonculus” does not match in orientation external visual input, then we don’t have the sensation of whole body ownership. But each body part can be owned separately.

We need further research to sort out what this means, precisely, but that is how we build the picture of how our brains work – one piece at a time.

There are a few practical implications of all this. The first gets back to my previous post about brain-machine interfaces. A patient can be made to feel as if they own and control a robotic prosthetic limb if they are given sensory feedback. The “illusion” of ownership will work with a fake limb. But also, we are at the beginning of virtual reality technology. It is intriguing that it may be possible to feel convincingly as if we own, occupy, and control a virtual avatar. That is why the tiny details of exactly how these circuits work is important – if we want to manipulate them precisely.

While it may be disturbing on some level, it is actually a good thing that our subjective sensations are all constructed illusions. This means our brains can function seamlessly with a constructed virtual reality.