Dec

29

2025

Definitely the most fascinating and perhaps controversial topic in neuroscience, and one of the most intense debates in all of science, is the ultimate nature of consciousness. What is consciousness, specifically, and what brain functions are responsible for it? Does consciousness require biology, and if not what is the path to artificial consciousness? This is a debate that possibly cannot be fully resolved through empirical science alone (for reasons I have stated and will repeat here shortly). We also need philosophy, and an intense collaboration between philosophy and neuroscience, informing each other and building on each other.

Definitely the most fascinating and perhaps controversial topic in neuroscience, and one of the most intense debates in all of science, is the ultimate nature of consciousness. What is consciousness, specifically, and what brain functions are responsible for it? Does consciousness require biology, and if not what is the path to artificial consciousness? This is a debate that possibly cannot be fully resolved through empirical science alone (for reasons I have stated and will repeat here shortly). We also need philosophy, and an intense collaboration between philosophy and neuroscience, informing each other and building on each other.

A new paper hopes to push this discussion further – On biological and artificial consciousness: A case for biological computationalism. Before we delve into the paper, let’s set the stage a little bit. By consciousness we mean not only the state of being wakeful and conscious, but the subjective experience of our own existence and at least a portion of our cognitive state and function. We think, we feel things, we make decisions, and we experience our sensory inputs. This itself provokes many deep questions, the first of which is – why? Why do we experience our own existence? Philosopher David Chalmers asked an extremely provocative question – could a creature have evolved that is capable of all of the cognitive functions humans have but not experience their own existence (a creature he termed a philosophical zombie, or p-zombie)?

Part of the problem of this question is that – how could we know if an entity was experiencing its own existence? If a p-zombie could exist, then any artificial intelligence (AI), even one capable of duplicating human-level intelligence, could be a p-zombie. If so, what is different between the AI and biological consciousness? At this point we can only ask these questions, some of them may need to wait until we actually develop human-level AI.

Continue Reading »

Dec

15

2025

As human civilization spreads into every corner of the world, human and animal territories are butting up against each other more intensely. This often doesn’t end well for the animals. This is also causing evolutionary pressures that are adapting some species to living in close proximity to humans.

As human civilization spreads into every corner of the world, human and animal territories are butting up against each other more intensely. This often doesn’t end well for the animals. This is also causing evolutionary pressures that are adapting some species to living in close proximity to humans.

Humans cause significant changes to the environment – we may, for example, clear forests in order to plant crops. We also convert a lot of land to human living spaces. We alter the ecosystem with lots of light pollution. We are also now warming the planet.

Humans also produce a lot of food and along with it a lot of food waste. One of the common rules of evolution is that if a resource exists, something will adapt to exploit it. Perhaps the most versatile species in terms of adapting to human sources of food is rats. They follow humans everywhere we go, and prosper in our shadow. New York city experiencing this phenomenon first hand – there is basically no effective way to deal with the rat problem in the city as long as they have a waste problem. They will need to significantly reduce the availability of food waste if they want to make any dent in the rat population.

There is another way that humans provide a selective pressure on the animals that live close to us – we kill aggressive animals. A recent study shows this effect in a population of brown bears that live in Italy, close to humans. This isolated population has become its own genetic subpopulation of brown bears with distinctive features, including a genetic profile associated with less aggressiveness. Make no mistake, these are still wild animals, and brown bears are a dangerous animal. But they are less aggressive than other brown bears.

Continue Reading »

Dec

11

2025

We are not close to mining asteroids, but the idea is intriguing enough to cause some serious study of the potential. The idea is simple enough – our solar system is full of chunks of rock with valuable minerals. If we could make it economically viable to mine even a tiny percentage of these asteroids the potential would be immense, a game changer for many types of resources. How valuable are asteroids?

We are not close to mining asteroids, but the idea is intriguing enough to cause some serious study of the potential. The idea is simple enough – our solar system is full of chunks of rock with valuable minerals. If we could make it economically viable to mine even a tiny percentage of these asteroids the potential would be immense, a game changer for many types of resources. How valuable are asteroids?

The range of potential value is extreme, but at the high end we have a large metal rich asteroid like 16 Psyche in the asteroid belt. Astronomers estimate that the iron in 16 Psyche alone is worth about $10,000 quadrillion on today’s market. By comparison the world’s current economic output is just over $100 trillion, so that’s 100,000 times the world’s annual economic output. Of course, the cost of extraction would be high and the market value would likely be dramatically affected by such a resource, but it shows the dramatic potential of mining asteroids. Some asteroids are rich in platinum-group metals or rare earths, which would be even more valuable. But even the more common carbonaceous asteroids would likely have minerals worth quadrillions.

Again, these figures are likely not the actual monetary value that would be profited from mining asteroids, but they indicate that it is very likely economically viable to do so. I am reminded of the fact that aluminum was more expensive than gold in the 19th century. Then a process for extracting and refining aluminum from dirt was found, and now it is worth about $1.30 a pound. Still the aluminum industry is worth about $300 billion today. Mining asteroids would have a similar effect on many industries.

Continue Reading »

Dec

08

2025

A new study reinforces the evidence for the safety and efficacy of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. That’s the TLDR, but let’s dive into the details.

reinforces the evidence for the safety and efficacy of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. That’s the TLDR, but let’s dive into the details.

Medical evidence is always rolled out in stages. First there is what we would consider preclinical evidence, or basic science. This could be initial uncontrolled clinical observations, or mechanistic animal or in vitro research. At some point we have sufficient evidence to generate a hypothesis that a specific treatment could be effective in treating a specific disease, enough to progress to human research. For FDA qualifying research, there are four specific phases. Phase I trials look at the safety of the intervention in usually healthy controls, while also answering basic questions and mechanism and effects. If there are no safety red-flags then the research progressed to a phase II trial, which look for preliminary evidence of efficacy, and further safety data. Again, if that data continues to look encouraging we can progress to a phase III trial, which is a larger and more rigorous trial designed to be definitive. Usually the FDA requires several phase III trials to grant approval of a drug for a specific indication. Then, once on the market there is phase IV trials, which look at data from more widespread use to confirm safety and effectiveness in the real world.

Looked at another way, we do research in the lab, then on dozens of people, then score to hundreds of people, then hundreds to thousands of people, and then finally on thousands to millions of people. Each step of the way we gain the ability to detect less and less common side effects in a broader set of people. Further, the types of evidence are designed to be complementary. Phase III trials, for example, are rigorously experimental, with highly defined populations with randomization to control as many variables as possible. Phase IV trials, on the other hand, are generally observational, designed to look at very large numbers of people in an uncontrolled setting – to determine how safe and effective the treatment is in real-world conditions.

Continue Reading »

Dec

01

2025

We have all likely had the experience that when we learn a task it becomes easier to learn a distinct but related task. Learning to cook one dish makes it easier to learn other dishes. Learning how to repair a radio helps you learn to repair other electronics. Even more abstractly – when you learn anything it can improve your ability to learn in general. This is partly because primate brains are very flexible – we can repurpose knowledge and skills to other areas. This is related to the fact that we are good at finding patterns and connections among disparate items. Language is also a good example of this – puns or witty linguistic humor is often based on making a connection between words in different contexts (I tried to tell a joke about chemistry, but there was no reaction).

We have all likely had the experience that when we learn a task it becomes easier to learn a distinct but related task. Learning to cook one dish makes it easier to learn other dishes. Learning how to repair a radio helps you learn to repair other electronics. Even more abstractly – when you learn anything it can improve your ability to learn in general. This is partly because primate brains are very flexible – we can repurpose knowledge and skills to other areas. This is related to the fact that we are good at finding patterns and connections among disparate items. Language is also a good example of this – puns or witty linguistic humor is often based on making a connection between words in different contexts (I tried to tell a joke about chemistry, but there was no reaction).

Neuroscientists are always trying to understand what we call the “neuroanatomical correlates” of cognitive function – what part of the brain is responsible for specific tasks and abilities? There is no specific one-to-one correlation. I think the best current summary of how the brain is organized is that it is made of networks of modules. Modules are nodes in the brain that do specific processing, but they participate in multiple different networks or circuits, and may even have different functions in different networks. Networks can also be more or less widely distributed, with the higher cognitive functions tending to be more complex than specific simple tasks.

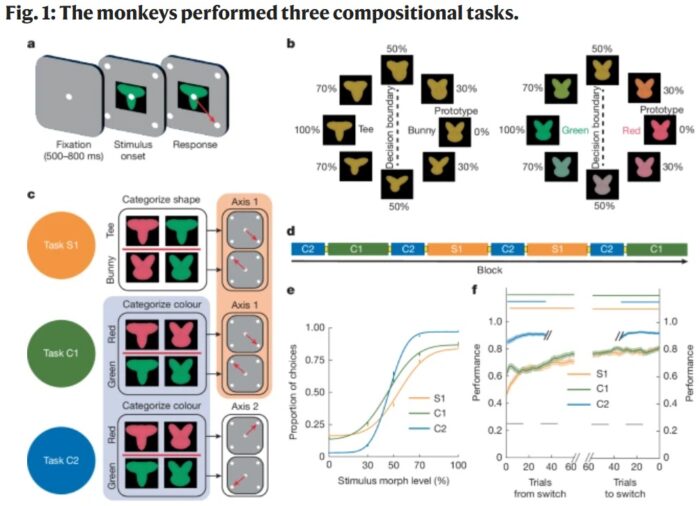

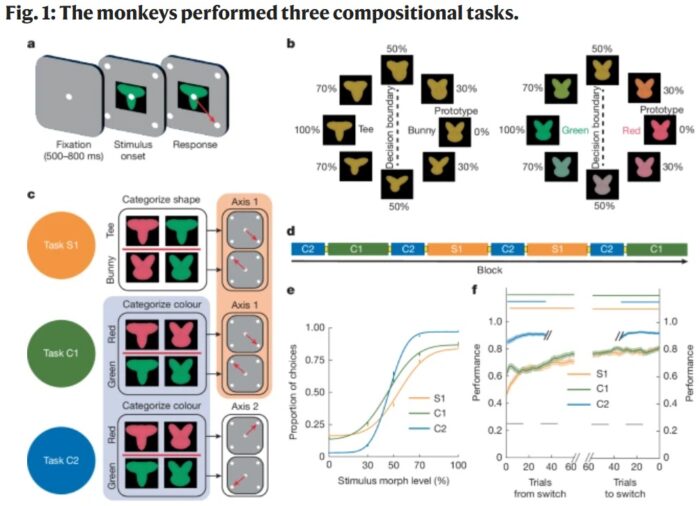

What, then, is happening in the brain when we exhibit this cognitive flexibility, repurposing elements of one learned task to help learn a new task? To address this question Princeton researchers looked at rhesus macaques. Specifically they wanted to know if primates engage in what is called “compositionality” – breaking down a task into specific components that can then be combined to perform the task. Those components can then be combined in new arrangements to compose a new task, like building with legos.

Continue Reading »

Definitely the most fascinating and perhaps controversial topic in neuroscience, and one of the most intense debates in all of science, is the ultimate nature of consciousness. What is consciousness, specifically, and what brain functions are responsible for it? Does consciousness require biology, and if not what is the path to artificial consciousness? This is a debate that possibly cannot be fully resolved through empirical science alone (for reasons I have stated and will repeat here shortly). We also need philosophy, and an intense collaboration between philosophy and neuroscience, informing each other and building on each other.

Definitely the most fascinating and perhaps controversial topic in neuroscience, and one of the most intense debates in all of science, is the ultimate nature of consciousness. What is consciousness, specifically, and what brain functions are responsible for it? Does consciousness require biology, and if not what is the path to artificial consciousness? This is a debate that possibly cannot be fully resolved through empirical science alone (for reasons I have stated and will repeat here shortly). We also need philosophy, and an intense collaboration between philosophy and neuroscience, informing each other and building on each other.

As human civilization spreads into every corner of the world, human and animal territories are butting up against each other more intensely. This often doesn’t end well for the animals. This is also causing evolutionary pressures that are adapting some species to living in close proximity to humans.

As human civilization spreads into every corner of the world, human and animal territories are butting up against each other more intensely. This often doesn’t end well for the animals. This is also causing evolutionary pressures that are adapting some species to living in close proximity to humans. We are not close to mining asteroids, but the idea is intriguing enough to cause some serious study of the potential. The idea is simple enough – our solar system is full of chunks of rock with valuable minerals. If we could make it economically viable to mine even a tiny percentage of these asteroids the potential would be immense, a game changer for many types of resources. How valuable are asteroids?

We are not close to mining asteroids, but the idea is intriguing enough to cause some serious study of the potential. The idea is simple enough – our solar system is full of chunks of rock with valuable minerals. If we could make it economically viable to mine even a tiny percentage of these asteroids the potential would be immense, a game changer for many types of resources. How valuable are asteroids?

We have all likely had the experience that when we learn a task it becomes easier to learn a distinct but related task. Learning to cook one dish makes it easier to learn other dishes. Learning how to repair a radio helps you learn to repair other electronics. Even more abstractly – when you learn anything it can improve your ability to learn in general. This is partly because primate brains are very flexible – we can repurpose knowledge and skills to other areas. This is related to the fact that we are good at finding patterns and connections among disparate items. Language is also a good example of this – puns or witty linguistic humor is often based on making a connection between words in different contexts (I tried to tell a joke about chemistry, but there was no reaction).

We have all likely had the experience that when we learn a task it becomes easier to learn a distinct but related task. Learning to cook one dish makes it easier to learn other dishes. Learning how to repair a radio helps you learn to repair other electronics. Even more abstractly – when you learn anything it can improve your ability to learn in general. This is partly because primate brains are very flexible – we can repurpose knowledge and skills to other areas. This is related to the fact that we are good at finding patterns and connections among disparate items. Language is also a good example of this – puns or witty linguistic humor is often based on making a connection between words in different contexts (I tried to tell a joke about chemistry, but there was no reaction).