May 22 2020

Storing Carbon to Mitigate Climate Change

Here is a tiny bit of good news on the climate change front: A new analysis finds that there is more than enough storage space globally to fit the carbon we would need to capture and store if we wish to meet our climate change goals. The found:

Here is a tiny bit of good news on the climate change front: A new analysis finds that there is more than enough storage space globally to fit the carbon we would need to capture and store if we wish to meet our climate change goals. The found:

No more than 2700 Gt of storage resource is required under any scenario to meet the most ambitious climate change mitigation targets.

Meanwhile current estimates of global carbon storage capacity are around 10,000 Gt. This does not mean we will meet our targets, it only means that global carbon storage capacity will not be a limiting factor. It’s always fun to learn that something you didn’t even know was a problem turns out not to be a problem anyway. But let’s break this down a bit.

The study modeled climate change mitigation scenarios using different assumptions about reducing fossil fuel use, increasing renewable energy, electrifying the transportation sector, energy efficiency, and carbon capture. They ran 1,200 different scenarios through the simulation, and found that under any scenario the maximum amount of carbon storage that would be necessary to meet the goal of no more than 2 C warming is 2,700 Gt. How much storage we would actually need, however, varied considerably based upon the other details. Specifically, the faster we ramp up carbon capture and storage (CCS) the less storage space we will ultimately need. The longer we wait, the harder it will be, and the more we will need to make up for lost time with CCS.

Also, like many resources, space for CCS varies in terms of convenience and cost. The more space we need, the more we will have to rely upon the less and less efficient storage space. So the longer we delay climate mitigation, the harder it will get.

The authors also model how quickly we are currently increasing our CCS capacity and found that it is on track to meet our goals. We always have to be skeptical, however, of extrapolating current linear trends over a large magnitude. Such extrapolations tend not to be very predictive. Especially with technology – scaling up has the potential to run into many possible limiting factors. But at least it seems possible that if we continue to increase CCS this can be one important component of our climate change mitigation strategy.

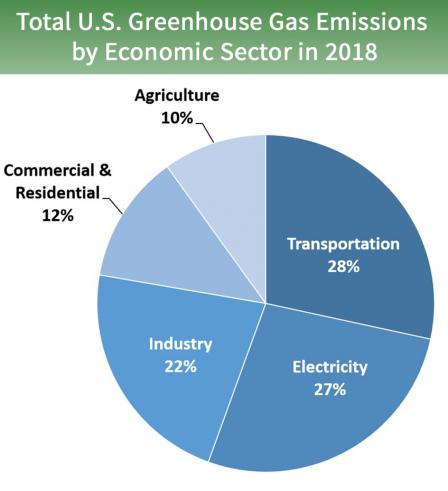

But the authors also emphasize that under no scenario is CCS good enough on its own. It must be combined with reductions in CO2 release through the other mechanisms mentioned. Specifically we need to rapidly decarbonize our energy infrastructure while converting as much transportation to electrical as quickly as possible. This will shift some energy production from the gasoline in your car to power plants contributing to the grid, which makes it even more important to decarbonize grid electricity. If we add industry, such as cement, steel, and plastic production, we are up to 78% of CO2 emissions. This is where the game will be either won or lost.

I have discussed previously the issues surrounding how to decarbonize our energy infrastructure. In brief, it seems that there is no one solution. We need to leverage renewable energy, grid storage, and nuclear power if we are going to maximize our chance of meeting reasonable climate goals. Replacing gasoline base cars with electrical cars is happening. The technology is here and it works. The question is, will it happen fast enough. Probably the biggest single factor affecting that is battery technology. We need cheaper, smaller, higher capacity batteries. This is slowly and steadily happening, and perhaps will be fast enough to do the trick, but a nice battery advance would be welcome.

Carbon from industry is tricky, because there is no clear path forward. The many different processes that contribute to industrial CO2 need to be researched to find lower CO2 alternatives. This is happening, but this is the hardest to predict. For electricity production and transportation we know exactly what to do – we just need to do it. For industrial CO2 we need to research alternatives, and we cannot predict yet for many such sources how things will work out.

The commercial and residential sector is mainly about energy efficiency. Buildings need to be energy efficient, we should all be using LED bulbs, and we need to reduce waste. But there is simply not that much capacity in this sector to make a huge difference. It is in everyone’s own self-interest to be energy efficient, because it saves you money. It’s a bonus that it also helps the environment. But individual habits and energy efficiency are simply not going to determine the outcome of climate change.

In fact, there is a long tradition of industry trying to focus attention on the role of individual habits, because it takes the focus and the pressure off of them. This is often a deliberate campaign of shifting responsibility. A classic example of this is the anti-littering campaign starting in the 1950s. While no one is pro-litter, and we should all take responsibility for our own littering, the “Keep America Beautiful” anti-littering campaign was a cynical product of industry trying to take heat off themselves for changes in the industry that were resulting in more littering. They were an attempt to oppose legislation on industry – and it worked.

Focusing on individual behavior to mitigate climate change is similar. Sure, we should all be reasonably energy efficient. Again, this saves money and why not all do our part. But individual behavior just nibbles around the edges of the problem. We need change in the various industries that are causing most of the carbon release, and that may take legislation.

The same is true for agriculture. Right now it is responsible for 10% of CO2 release. This is not insignificant, but this is also not the sector that is likely to make a difference. If we shifted our agricultural infrastructure to one that was maximally carbon efficient, how much would it really save? How efficient can we get? Actually, when it comes to agriculture, the single most important factor is land use. Cutting down a forest for farmland has a bigger negative impact on climate change than any other factor in agriculture. What we should focus on in this sector is maximizing land use. Each piece of land should be used for its optimal function, whether as a natural carbon sink, for growing a specific type of crop, or for grazing. We should also decrease our overall meat consumption, but we don’t have to eliminate it, and in fact it would probably be inefficient to try to completely eliminate meat (but this is a complex topic I will probably have to delve into separately).

The bottom line is that we can squeeze a few percent out of the residential/commercial sector, and a few percent out of the agriculture sector, but these are not where the big difference will be make. We need to virtually eliminate the CO2 from the transportation and electricity sectors. We know how to do this, we can do this, we just need to do it. Political will is the only limiting factor. We also need to explore how to reduce CO2 from the industrial sector, but this is more of an unknown.

Meanwhile, CCS is another option that will help the entire effort. Ideally we can capture and store enough CO2 to offset the emissions we cannot get rid of. We know how to do this, we now know we have enough physical space to store enough carbon. The most significant variable now is how well current methods of CCS will scale up to the levels necessary to be enough. Scaling up is not a trivial factor, so we will see. Meanwhile, new methods of CCS continue to be researched, so we may find a game changer at some point. But again, that’s an unknown.