Mar 21 2023

Unifying Cognitive Biases

Are you familiar with the “lumper vs splitter” debate? This refers to any situation in which there is some controversy over exactly how to categorize complex phenomena, specifically whether or not to favor the fewest categories based on similarities, or the greatest number of categories based on every difference. For example, in medicine we need to divide the world of diseases into specific entities. Some diseases are very specific, but many are highly variable. For the variable diseases do we lump every type into a single disease category, or do we split them into different disease types? Lumping is clean but can gloss-over important details. Splitting endeavors to capture all detail, but can create a categorical mess.

Are you familiar with the “lumper vs splitter” debate? This refers to any situation in which there is some controversy over exactly how to categorize complex phenomena, specifically whether or not to favor the fewest categories based on similarities, or the greatest number of categories based on every difference. For example, in medicine we need to divide the world of diseases into specific entities. Some diseases are very specific, but many are highly variable. For the variable diseases do we lump every type into a single disease category, or do we split them into different disease types? Lumping is clean but can gloss-over important details. Splitting endeavors to capture all detail, but can create a categorical mess.

As is often the case, an optimal approach likely combines both strategies, trying to leverage the advantages of each. Therefore we often have disease headers with subtypes below to capture more detail. But even there the debate does not end – how far do we go splitting out subtypes of subtypes?

The debate also happens when we try to categorize ideas, not just things. Logical fallacies are a great example. You may hear of very specific logical fallacies, such as the “argument ad Hitlerum”, which is an attempt to refute an argument by tying it somehow to something Hitler did, said, or believed. But really this is just a specific instance of a “poisoning the well” logical fallacy. Does it really deserve its own name? But it’s so common it may be worth pointing out as a specific case. In my opinion, whatever system is most useful is the one we should use, and in many cases that’s the one that facilitates understanding. Knowing how different logical fallacies are related helps us truly understand them, rather than just memorize them.

A recent paper enters the “lumper vs splitter” fray with respect to cognitive biases. They do not frame their proposal in these terms, but it’s the same idea. The paper is – Toward Parsimony in Bias Research: A Proposed Common Framework of Belief-Consistent Information Processing for a Set of Biases. The idea of parsimony is to use to be economical or frugal, which often is used to apply to money but also applies to ideas and labels. They are saying that we should attempt to lump different specific cognitive biases into categories that represent underlying unifying cognitive processes.

Of course, that is exactly where the rubber meets the road – do multiple recognized cognitive biases stem from the same underlying cognitive process? I think the answer is very likely yes, and they present a compelling argument for some specific lumping. This, I think, is the natural evolution of cognitive bias research.

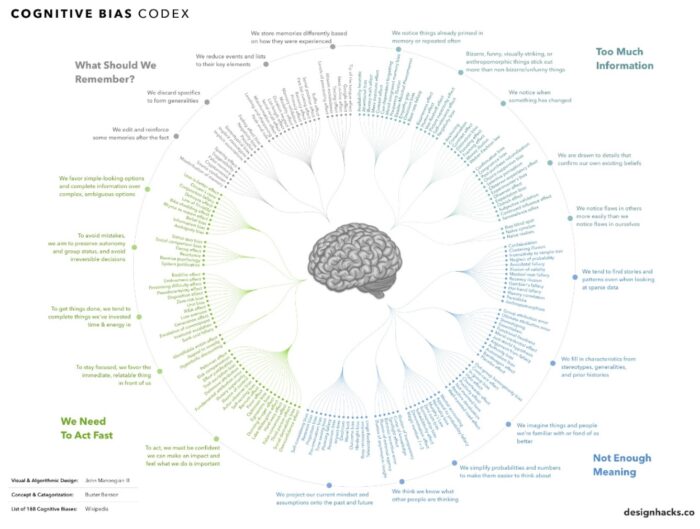

A cognitive bias represents a bias toward or away from one outcome in our information processing. Cognitive biases can affect what we perceive, notice, remember, believe, assume, and conclude. It can affect our estimates of numbers and probability. Biases often employ subconscious logic, hidden assumptions, or unstated major premises. That humans are massively biases in numerous ways in our information processing and belief formation has been well-established by research. One of the key components to critical thinking is understanding and compensating for our own biases.

Understanding cognitive biases had to start at the maximal splitting end of the spectrum, as a consequence of psychological research. Such research requires what is called a research paradigm or construct. You have to look at and measure something specific. We can’t “read minds” so we must infer what is happening in the brains of research subjects based upon the construct. Sometimes those inferences prove later to be wrong, or just too simplistic. For example, there is the anchoring bias. In one research paradigm subjects are asked to guess how much a house costs based on a picture. Another group is first asked, “Does this house cost more or less than $100,000” and a third group is asked, “Does this house cost more or less than $500,000”. All subjects are looking at the same picture, but the third group will guess a price much higher on average than the first group. Each group has anchored their assessment to the priming question.

I other words, cognitive biases are identified and named based on the research construct used, and they can be highly specific. The psychologists in the current paper ask, however, shouldn’t we also be trying to unify different cognitive biases as specific cases stemming from the same underlying cognitive phenomenon? My answer is – Yeah, of course. But that’s tricky, because it requires another level of inference. We never know what people are actually thinking, and often people don’t know what they are thinking. We generally are not aware of the subconscious calculations being made by algorithms in our brain. What we do is invent an explanation in retrospect to justify our decisions and beliefs. Look up the split-brain research for dramatic examples of this.

But some unification may seem reasonable, even ineluctable. For example, they propose that the spotlight effect (the tendency to overestimate the degree to which others notice ourselves) and the false consensus bias (the assumption that most people agree with us) are both manifestations of the same underlying bias, that our own experiences are a reasonable reference. What I notice other people notice, and what I believe other people believe.

They refer to this as “belief consistent information processing”. Biases, they argue, start with a belief, and these specific cognitive bias manifestations stem from the underlying belief. In the example above, the belief is that oneself is a reasonable reference point from which to make judgements of others.

I think this process is invaluable, and will help us dig deeper in the nature of cognitive biases. But there are two tricky aspects to this endeavor. The first is that we need to find a way of testing hypotheses that stem from this process. This will require designing and testing other psychological constructs. The second is – how will we know when we have hit psychological bedrock? Once we unify several biases into the same underlying belief, perhaps we can dig even deeper, unifying those underlying beliefs into a more fundamental psychological phenomenon. While I think all of this is hugely useful, I also think we need to recognize the inherent limitations of this kind of psychological research, that we are making inferences from constructs. In order to hit that bedrock I think we will need a multi-disciplinary approach, correlating psychological research with neuroscience research – what networks in the brain are being activated and what do they do? But even that might not be enough. I suspect that the most useful research will happen when we have digital human brains (either virtual or hardwired) that we can experiment on with complete control over and monitoring of the activity of different networks and modules.

But that is a ways off, so in the meantime we need to make due with constructs and thoughtful inference, perhaps informed by some fMRI studies.