Sep 07 2018

Probiotics – It’s Complicated

A new detailed study of the effects of probiotics on the gastrointestinal microbiome shows how complex this subject is. Unfortunately, the reporting is significantly oversimplifying the results. The BBC reports:

A new detailed study of the effects of probiotics on the gastrointestinal microbiome shows how complex this subject is. Unfortunately, the reporting is significantly oversimplifying the results. The BBC reports:

A group of scientists in Israel claim foods that are packed with good bacteria – called probiotics – are almost useless.

That’s not actually what they said, at least according to my read.

Probiotics are pills or foods that contain live friendly bacteria, which are meant to support the beneficial bacteria that live in our guts. This basic idea is not pseudoscience. It is quite reasonable – however, the science of probiotics is very immature. We are still in a phase where we are discovering more and more complexity, and struggling to find any clear therapeutic gains. Meanwhile, the marketplace is making claims that go way beyond the science, and is based on very simplistic notions of how the microbiome works.

In the last decade or so we have demonstrated that the microbiome is an ecosystem at homeostasis. People have about 100 bacterial species in their gut microbiome, which not only colonize their mucous membranes, they keep out other bacterial species. This is an important part of our immune defense – the microbiome prevents infection by harmful bacteria. Further, you can’t just throw one or a few species into an ecosystem and expect to change it.

The clinical evidence reflects this view. Despite a plethora of products marketed for health maintenance, there is no evidence (and low plausibility) for the notion that consuming probiotics has benefits for healthy individuals.

We have also learned that people fall into one of four (perhaps more) stable ecosystems – so there are microbiome types. We tend to inherit our microbiome type from our family.

There may be some benefits to probiotics in specific pathological conditions – in premature infants, when taking certain antibiotics, and in certain gastrointestinal disorders. However, even in these conditions we need more study.

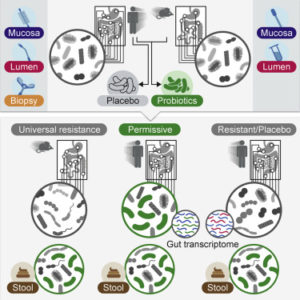

The new study adds a bit more complexity to this picture. The researchers surgically sampled bacteria from several places along the GI tract and in the stool. They then gave subjects either a cocktail of 11 probiotic species, or placebo. The primary finding was that in half of the subject, there was essentially no difference between those treated with 11 probiotics and placebo. In the other half, there were some changes indicating activity of the probiotic species.

However, in all the subjects taking probiotics the introduced species showed up in their stool. The researchers interpreted this to mean that the introduced species just passed through the gut into the stool without ever taking up shop. Therefore, in future research, using stool samples (while convenient) tells us nothing about probiotic activity.

The other major implication for their study is that people tend to be either permissive or resistant to introduced bacteria. Therefore, there is no one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to probiotics. There are also regional as well as family and individual differences. This fits with the previous research showing different microbiome types.

In a separate study they also showed, using their sampling technique, that taking probiotics to offset the effects of antibiotics (which reduces the host microbiome) seems to delay the reestablishment of the normal microbiome. Therefore it could have a harmful effect.

Conclusion

The bottom line of this and existing research is that the gut microbiome is complicated, and evaluating probiotic interventions is likewise complicated. At the very least we need to recognize several facts:

- The gut microbiome is a complex and stable ecosystem that resists change (that’s actually part of its core function).

- Stool samples are not an adequate way to asses the microbiome or the effects of probiotics.

- Probiotics cannot be assumed to be harmless in all situations.

However, the potential of using the microbiome to affect biological change appears to be large. Gut bacteria affect our immune system and our metabolism of certain foods. They may affect our risk of obesity or diabetes, and even auto-immune diseases. It is therefore worth study.

But developing effective interventions is not going to be easy. Further, they are likely going to have to be individualized – you will need your microbiome characteristics determined and any intervention tailored to you.

For now I think it is clear that taking routine probiotics for general health is worthless. Meanwhile, using probiotics for specific health issues is a complex and evolving area with a lot of potential, but we still have a lot to learn.