Aug 25 2023

First Mission To Remove Space Debris

I know you don’t need one more thing to worry about, but I have already written about the growing problem of space debris. At least this update is about a mission to help clear some of that debris – ClearSpace-1. This is an ESA mission which they contracted out to a Swiss company, Clearspace SA, who is making a satellite whose purpose is to grab large pieces of space junk and de-orbit it.

I know you don’t need one more thing to worry about, but I have already written about the growing problem of space debris. At least this update is about a mission to help clear some of that debris – ClearSpace-1. This is an ESA mission which they contracted out to a Swiss company, Clearspace SA, who is making a satellite whose purpose is to grab large pieces of space junk and de-orbit it.

The problem this mission is trying to solve is the fact that we have put millions of pieces of debris into various orbits around the Earth. While space is big, usable near-Earth orbits are finite, and if you put millions of pieces of debris there zipping around at fast speeds, there will be collisions. The worst-case scenario is what’s called a Kessler cascade, in which a collision causes more debris which then increases the probability of further collisions which increases the amount of debris, and the cycle continues. This won’t be an event so much as a process that unfolds over a long period of time. But it has the potential of rendering Earth orbit increasingly dangerous to the point of being unusable. It also makes the task of cleaning up orbit exponentially more difficult.

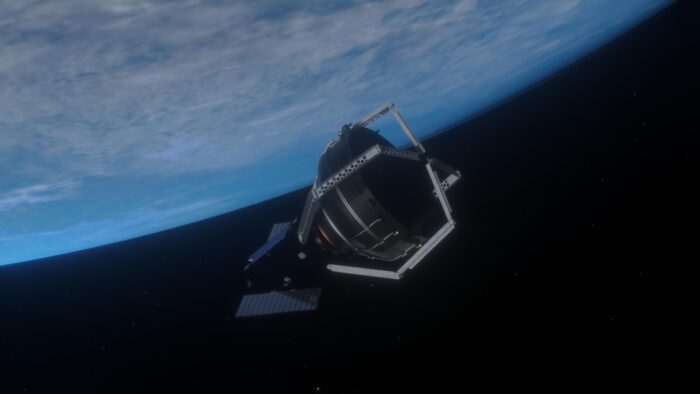

The Clearspace craft looks like a mechanical squid with 4 arms which can grab tightly onto a large piece of space debris. The planned first mission with target the upper stage of Vespa, part of the ESA Vega launcher. This is a 112 kg target. Once it grabs the debris it with then undergo a controlled deorbit. The mission is planned for 2026, and if successful will be the first mission of its kind. This is a proof-of-concept mission, because removing one piece of large debris is insignificant compared to how much debris is already up there. But we need to demonstrate that the whole system works, and we also need to confirm how much each such mission will cost.

This approach will only work for large pieces of debris (but not too large), but in the range of many upper rocket stages, small satellites or pieces of satellites. This is therefore not a global solution for all types of space debris, but can target perhaps some of the most dangerous debris, large chunks that can kick off a Kessler cascade. This will still leave behind millions of smaller bits of debris, but it is still a partial solution and will help. Perhaps this approach can be adapted to progressively smaller pieces of debris, with the robot arms being fitted with a net.

Ironically illustrating the problem, recent observations of the Vespa component that they plan to target with ClearSpace-1 shows that it is surrounded by smaller debris. It has apparently already been struck by a piece of space debris, causing smaller pieces to break off. The pieces are all in the same orbit so they stay roughly together. This should not impede the CeearSpace-1 mission,

This approach is inherently limited, however, and so will likely only be deployed for these large bits of debris. The problem is that in order to grab a piece of debris you have to match its orbit. You can’t simply go to it, you have to match its orbital vector, both direction and velocity. This takes fuel. Once such a debris-grabbing satellite grabs one piece of debris, it will likely not have the fuel to target another. This approach, therefore, will likely only be feasible for either large single pieces of debris or a large collection of debris all orbiting together.

But again, every piece of debris we remove from orbit reduces the chance of a collision and the probability or speed of a Kessler cascade. But clearly more than the occasional Clearspace mission needs to be done. Another approach is to have powerful land-based lasers target individual pieces of debris, essentially pushing them enough to slow them down so that they deorbit and burn up in the atmosphere.

Clearspace SA is also not the only company working on this technology. I wrote previously about Astroscale, a Japanese company that offers the same service, in addition to preparing satellites for deorbiting at the end of their life, extending the life of existing satellites, and inspection of satellites and debris.

The goal of such services is sustainability. Right now our use of Earth orbit, especially low Earth orbit, is not sustainable. There is already too much debris, and we can’t afford to clutter usable orbits with more debris. In order to make Earth orbit sustainable we need to do several things. First, we need to stop leaving more junk in space. This means that everything we put up there must have a plan for how it will be removed from orbit once its lifespan is over. This includes building rockets that deorbit any upper stages that would otherwise just stay in orbit. That’s step one – stop putting more junk in space. Further we need to remove as much of the existing debris as possible. We are never going to get rid of every paint chip and rogue bolt, but we can start with the largest pieces of space debris and work our way down.

This all means that we need enforceable international standards. Voluntary standards are fine, if everyone agrees to them. It essentially should be impossible to do business if you are a space company that does not follow accepted standards. This is another case of an externalized cost – it is cheaper to put something in orbit without making any provision for deorbiting space junk, but this just externalizes the cost to others. Everyone need to pay to clean up their own junk.