Oct

03

2024

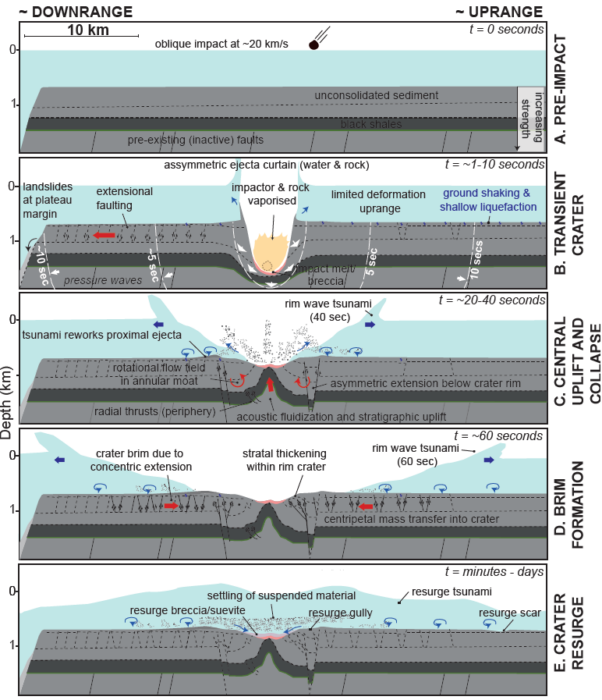

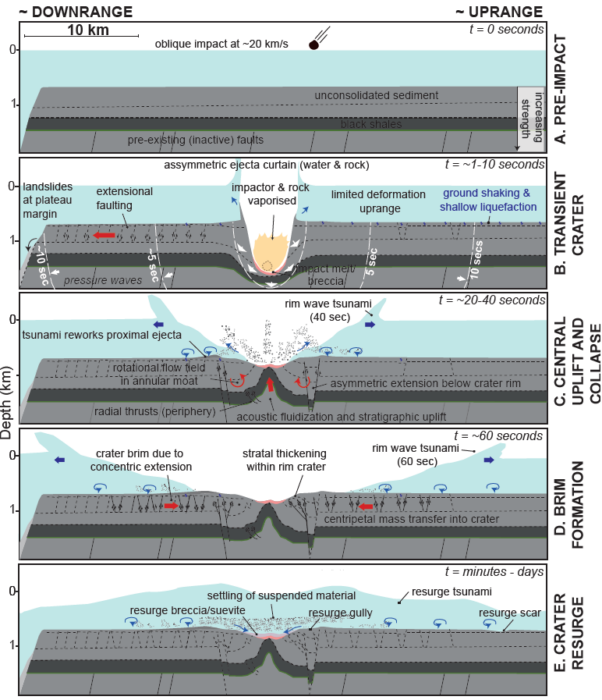

It is now generally accepted that 66 million years ago a large asteroid smacked into the Earth, causing the large Chicxulub crater off the coast of Mexico. This was a catastrophic event, affecting the entire globe. Fire rained down causing forest fires across much of the globe, while ash and debris blocked out the sun. A tsunami washed over North America – one site in North Dakota contains fossils from the day the asteroid hit, including fish with embedded asteroid debris. About 75% of species went extinct as a result, including all non-avian dinosaurs.

It is now generally accepted that 66 million years ago a large asteroid smacked into the Earth, causing the large Chicxulub crater off the coast of Mexico. This was a catastrophic event, affecting the entire globe. Fire rained down causing forest fires across much of the globe, while ash and debris blocked out the sun. A tsunami washed over North America – one site in North Dakota contains fossils from the day the asteroid hit, including fish with embedded asteroid debris. About 75% of species went extinct as a result, including all non-avian dinosaurs.

For a time there has been an alternate theory that intense vulcanism at the Deccan Traps near modern-day India is what did-in the dinosaurs, or at least set them up for the final coup de grace of the asteroid. I think the evidence strongly favors the asteroid hypothesis, and this is the way scientific opinion has been moving. Although the debate is by no means over, a majority of scientists now accept the asteroid hypothesis.

But there is also a wrinkle to the impact theory – perhaps there was more than one asteroid impact. I wrote in 2010 about this question, mentioning several other candidate craters that seem to date to around the same time. Now we have a new candidate for a second KT impact – the Nadir crater off the coast of West Africa.

Geologists first published about the Nadir crater in 2022, discussing it as a candidate crater. They wrote at the time:

“Our stratigraphic framework suggests that the crater formed at or near the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary (~66 million years ago), approximately the same age as the Chicxulub impact crater. We hypothesize that this formed as part of a closely timed impact cluster or by breakup of a common parent asteroid.”

Continue Reading »

Jul

30

2024

The topic of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) is a great target for science communication because public attitudes have largely been shaped by deliberate misinformation, and the research suggests that those attitudes can change in response to more accurate information. It is the topic where the disconnect between scientists and the public is the greatest, and it is the most amenable to change.

The topic of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) is a great target for science communication because public attitudes have largely been shaped by deliberate misinformation, and the research suggests that those attitudes can change in response to more accurate information. It is the topic where the disconnect between scientists and the public is the greatest, and it is the most amenable to change.

The misinformation comes in several forms, and one of those forms is the umbrella claim that GMOs have been bad for farmers in various ways. But this is not true, which is why I have often said that people who believe the misinformation should talk to farmers. The idea is that the false claims against GMOs are largely based on a fundamental misunderstanding of how modern farming works.

There is another issue here, which falls under another anti-GMO strategy – blaming GMOs for any perceived negative aspects of the economics of farming. Like in many industries, farm sizes have grown, and small family farms (analogous to mom-and-pop stores) have given way to large corporate owned agricultural conglomerates. This is largely due to consolidation, which has been happening for over a century (long before GMOs). It happens because larger farms have an economy of scale – they can afford more expensive high technology farm equipment. They can spread out their risk more. They are more productive. And when a small farm owner retires without a family to leave it to, they tend to consolidate with a larger farm. Also, government subsidies tend to favor larger farms.

Continue Reading »

May

24

2024

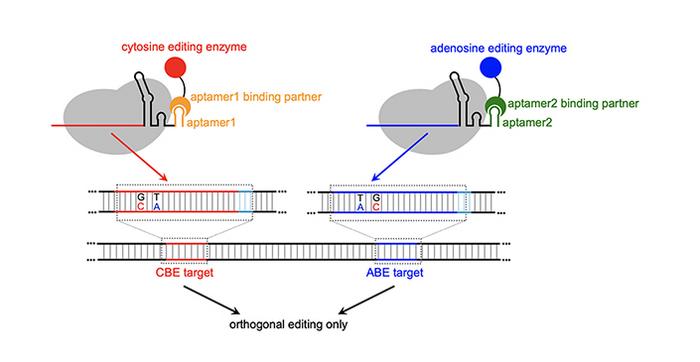

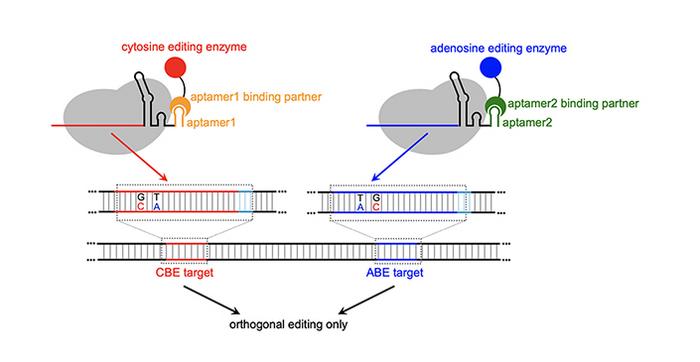

Have you memorized yet what CRISPR stands for – clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats? Well, now you can add MOBE to the list – multiplexed orthogonal base editor. Base editors are not new, they are basically enzymes that will change one base – C (cytosine), T (thymine), G (guanine), A (adenosine) – in DNA to another one, so a C to a T or a G to an A. MOBE is a guided system for making multiple desired base edits at once.

Have you memorized yet what CRISPR stands for – clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats? Well, now you can add MOBE to the list – multiplexed orthogonal base editor. Base editors are not new, they are basically enzymes that will change one base – C (cytosine), T (thymine), G (guanine), A (adenosine) – in DNA to another one, so a C to a T or a G to an A. MOBE is a guided system for making multiple desired base edits at once.

This is a complementary system to CRISPR, which targets a sequence of DNA and then uses Cas9 or a similar payload to make a double-stranded cut in the DNA. The cells natural repair system can then be leveraged to make changes during the repair process, such as inserting a new genetic sequence. In this way, and with different payloads, CRISPR can make targeted gene insertions or deletions, kill targeted cell types, or turn genes off and back on again.

MOBE cannot insert entire genes. Rather, systems like this can make single base edits. What is new about the MOBE system is that it can make multiple different types of edits at once. Some single base edits can change the nature of the resulting protein. Many single base changes in DNA are “silent” meaning that they do not alter the resulting amino acid that is coded for, because each amino acid has 3-4 similar three base pair codes. It’s also possible that a single base mutation will change the amino acid coded for, but the new amino acid is structurally similar to the previous one, so no conformational change in the protein results. But some point mutations will change one amino acid for a different one with a different effect – turning a straight line into a kink, for example. These alter the three dimensional folded structure of the protein, and therefore its function. Some point mutations may also change the code to what is called a stop codon, ending the production of the protein at that point and dramatically changing its structure.

Continue Reading »

May

21

2024

For decades scientists were confused by Antarctic sea ice. Climate models predict that it should be decreasing, and yet it has been steadily and slowly increasing. It also made for a great talking point for climate change deniers – superficially it seems like counter evidence to the global warming narrative, and at least paints scientists as if they don’t really know what’s going on.

For decades scientists were confused by Antarctic sea ice. Climate models predict that it should be decreasing, and yet it has been steadily and slowly increasing. It also made for a great talking point for climate change deniers – superficially it seems like counter evidence to the global warming narrative, and at least paints scientists as if they don’t really know what’s going on.

That talking point was never a good one. It was really just an excellent example of the bad faith strategies of deniers and a misunderstanding of how science works, and also how climate works. Scientists pointed out that “global warming” does not mean that the planet is warming everywhere equally. This is why “climate change” is a better term – it is more technically precise. The climate is changing due to human activity, and while there is an overall warming trend to this change, there is a lot of local variation. For example, while Antarctic sea ice was increasing, the ice shelfs of Antarctica itself were losing mass. Also, sea ice loss in the Artic more than offset the increase in the Antarctic, and global ice has been steadily decreasing.

The climate is a complex and dynamic process, and any change over time is likely to have a lot of moving and interacting parts. It is a lot easier to model and predict net global trends than it is to model every local reaction to those trends. But this situation did set up yet another meta-experiment. Deniers claimed that global climate change itself is just a temporary fluctuation in a complex system. Some places are warming, others are cooling, and it all will eventually come out in the wash. Meanwhile, the dominant scientific opinion was that greenhouse gases are causing climate forcing, resulting in directional climate change with complex local effects but clear global trends. Eventually these global trends will dominate any short time-scale or regionally local fluctuations.

Continue Reading »

May

17

2024

The Egyptian pyramids, and especially the Pyramids at Giza, have fascinated people probably since their construction between 4700 and 3700 years ago. They are massive structures, and it boggles the mind that an ancient culture, without the benefit of any industrial technology, could have achieved such a feat. This has led to endless speculation, especially in modern times, that perhaps some lost advanced civilization was at work, or maybe aliens.

The Egyptian pyramids, and especially the Pyramids at Giza, have fascinated people probably since their construction between 4700 and 3700 years ago. They are massive structures, and it boggles the mind that an ancient culture, without the benefit of any industrial technology, could have achieved such a feat. This has led to endless speculation, especially in modern times, that perhaps some lost advanced civilization was at work, or maybe aliens.

This view has been criticized as being partly driven by racism – whenever some amazing artifact of non-European culture is discovered, it must be aliens, because those savages could not be responsible. But also it reflects our general fascination with the idea of aliens or lost civilizations (like Atlantis). And perhaps mostly it results from the fact that modern cultures tend to underestimate the intelligence and ingenuity of past and especially ancient cultures. We have a bias that pre-modern people were all superstitious, simple, and generally ignorant – with a few exceptions, like ancient Rome (which is Occidental, so that’s OK). You’ll notice that no one thinks the Colosseum was built by aliens – those Romans were clever.

In any case, we also tend to underestimate how effective simple engineering principles can be. The ancient Egyptians had all six of the basic engineering tools at their disposal – the wheel, lever, wedge, screw, inclined plane, and pulley. These tools can be leveraged to accomplish amazing feats – “Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it and I will move the world.”

Continue Reading »

May

02

2024

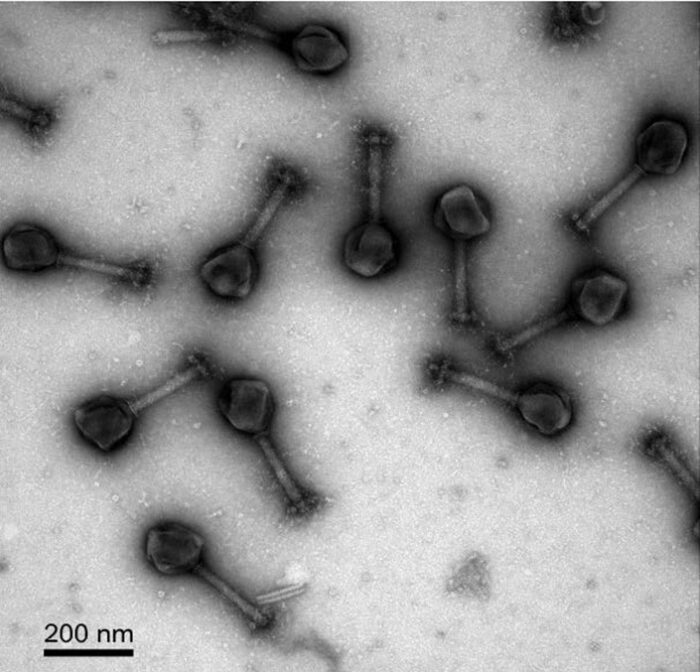

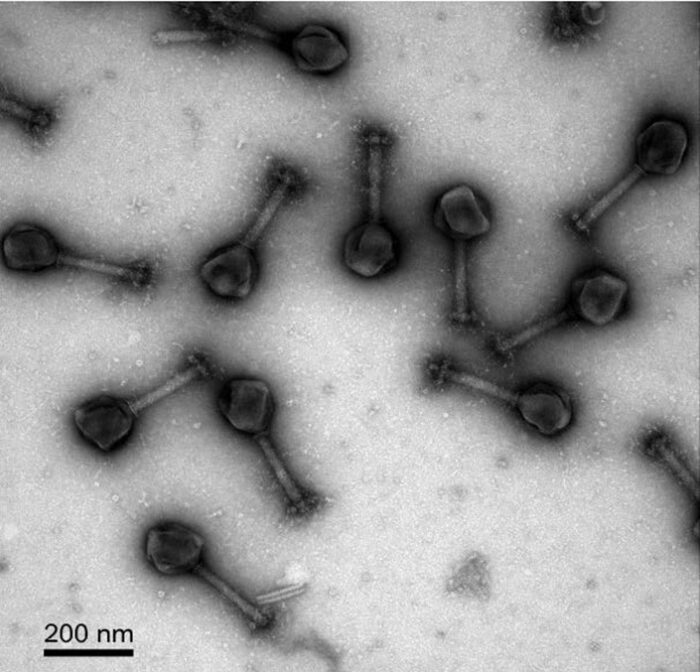

Bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria, are the most abundant form of life on Earth. And yet we know comparatively little about them. But in recent years phage research has taken off with renewed interest. This is partly driven by the availability of CRISPR-based tools for studying genomes. Interestingly, CRISPR itself is a gene-editing tool that derives from bacteria and archaea, which evolved the system as a defense against viruses that infect them and alter their genome. Now we are using CRISPR to investigate those very viruses, and perhaps use that knowledge as a tool to fight bacterial infections. Bacteria may have handed us the tools to fight bacteria.

Bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria, are the most abundant form of life on Earth. And yet we know comparatively little about them. But in recent years phage research has taken off with renewed interest. This is partly driven by the availability of CRISPR-based tools for studying genomes. Interestingly, CRISPR itself is a gene-editing tool that derives from bacteria and archaea, which evolved the system as a defense against viruses that infect them and alter their genome. Now we are using CRISPR to investigate those very viruses, and perhaps use that knowledge as a tool to fight bacterial infections. Bacteria may have handed us the tools to fight bacteria.

Most phage viruses are small, with genomes smaller than 200 kbp (kilo-base pairs). But a very few (93 so far) are larger than this, and known as jumbo phage viruses. The largest of these, Bacillus megaterium, is 497 kbp, which is only 87 kbp smaller than the smallest known bacterium, Mycoplasma genitalium. So essentially these are viruses that are almost as big as bacteria.

The jumbo phage viruses have been especially difficult to study for various technical reasons. For one, the filters that separate viruses from bacteria tend to trap the jumbo phages also. The genome has also been difficult to get access to. But CRISPR is changing that, giving us new tools to investigate these viruses. Researchers have recently published some interesting findings. When some jumbo viruses infect a bacterium they form a pseudonucleus that functions similar to the nucleus in eukaryotic cells, meaning that it is a walled-off section within the bacteria containing the viral genome. The purpose of forming this viral nucleus is to protect the genome from the bacterium, which will try to destroy or disable it before it can replicate.

Continue Reading »

Apr

26

2024

Most people have watched large flocks of birds. They are fascinating, and have interested scientists for a long time. How, exactly, do so many birds maintain their cohesion as a flock? It’s obviously a dynamic process, but what are the mechanisms?

Most people have watched large flocks of birds. They are fascinating, and have interested scientists for a long time. How, exactly, do so many birds maintain their cohesion as a flock? It’s obviously a dynamic process, but what are the mechanisms?

When I was young I was taught that each flock had a leader, and the other birds were ultimately just following that leader. When two smaller flocks combined into a larger flock, then one of those leaders become dominant and takes over the combined flock. But this explanation is largely untrue. It actually depends a great deal on the species of bird and the type of flock.

The “follow the leader” method is essentially what is happening with the V formations. These are obviously very different from the murmurations of small birds morphing like a giant flying amoeba. Some species, like pigeons, use a combined strategy, still following a leader, but more of a hierarchy of leaders, which can change over time.

For the more dynamic flocks, like starlings, researchers found that there is no leader or hierarchy. Every bird is just following the flock itself. It is a great example of an emergent phenomenon in nature. It’s like ants working in a colony or a bee hive – each individual bee or ant does not really know what the entire colony is doing, and there is no leader or foreman calling the shots or directing traffic. Each individual is just following a simple algorithm, and the collective complexity emerges from that.

Continue Reading »

Mar

04

2024

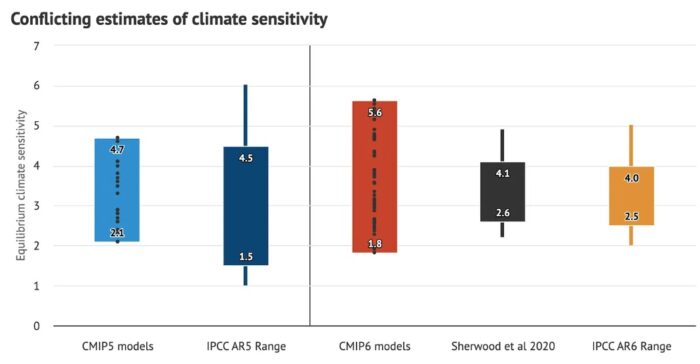

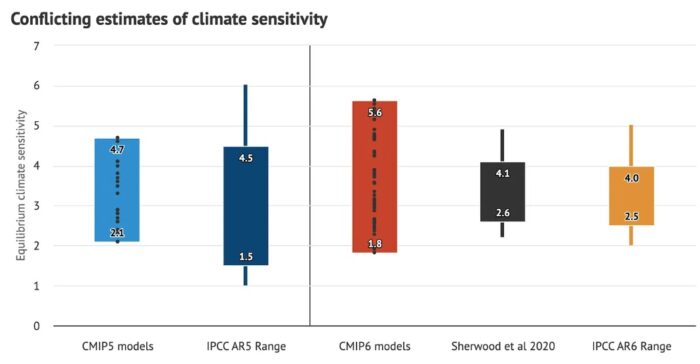

I love to follow kerfuffles between different experts and deep thinkers. It’s great for revealing the subtleties of logic, science, and evidence. Recently there has been an interesting online exchange between a physicists science communicator (Sabine Hossenfelder) and some climate scientists (Zeke Hausfather and Andrew Dessler). The dispute is over equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) and the recent “hot model problem”.

I love to follow kerfuffles between different experts and deep thinkers. It’s great for revealing the subtleties of logic, science, and evidence. Recently there has been an interesting online exchange between a physicists science communicator (Sabine Hossenfelder) and some climate scientists (Zeke Hausfather and Andrew Dessler). The dispute is over equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) and the recent “hot model problem”.

First let me review the relevant background. ECS is a measure of how much climate warming will occur as CO2 concentration in the atmosphere increases, specifically the temperature rise in degrees Celsius with a doubling of CO2 (from pre-industrial levels). This number of of keen significance to the climate change problem, as it essentially tells us how much and how fast the climate will warm as we continue to pump CO2 into the atmosphere. There are other variables as well, such as other greenhouse gases and multiple feedback mechanisms, making climate models very complex, but the ECS is certainly a very important variable in these models.

There are multiple lines of evidence for deriving ECS, such as modeling the climate with all variables and seeing what the ECS would have to be in order for the model to match reality – the actual warming we have been experiencing. Therefore our estimate of ECS depends heavily on how good our climate models are. Climate scientists use a statistical method to determine the likely range of climate sensitivity. They take all the studies estimating ECS, creating a range of results, and then determine the 90% confidence range – it is 90% likely, given all the results, that ECS is between 2-5 C.

Continue Reading »

Jan

08

2024

Categorization is critical in science, but it is also very tricky, often deceptively so. We need to categorize things to help us organize our knowledge, to understand how things work and relate to each other, and to communicate efficiently and precisely. But categorization can also be a hindrance – if we get it wrong, it can bias or constrain our thinking. The problem is that nature rarely cleaves in straight clean lines. Nature is messy and complicated, almost as if it is trying to defy our arrogant attempts at labeling it. Let’s talk a bit about how we categorize things, how it can go wrong, and why it matters.

Categorization is critical in science, but it is also very tricky, often deceptively so. We need to categorize things to help us organize our knowledge, to understand how things work and relate to each other, and to communicate efficiently and precisely. But categorization can also be a hindrance – if we get it wrong, it can bias or constrain our thinking. The problem is that nature rarely cleaves in straight clean lines. Nature is messy and complicated, almost as if it is trying to defy our arrogant attempts at labeling it. Let’s talk a bit about how we categorize things, how it can go wrong, and why it matters.

We can start with an example that might seem like a simple category – what is a planet? Of course, any science nerd knows how contentious the definition of a planet can be, which is why it is a good example. Astronomers first defined them as wandering stars – the points of light that were not fixed but seemed to wonder throughout the sky. There was something different about them. This is often how categories begin – we observe a phenomenon we cannot explain and so the phenomenon is the category. This is very common in medicine. We observe a set of signs and symptoms that seem to cluster together, and we give it a label. But once we had a more evolved idea about the structure of the universe, and we knew that there are stars and stars have lots of stuff orbiting around them, we needed a clean way to divide all that stuff into different categories. One of those categories is “planet”. But how do we define planet in an objective, intuitive, and scientifically useful way?

This is where the concept of “defining characteristic” comes in. A defining characteristic is, “A property held by all members of a class of object that is so distinctive that it is sufficient to determine membership in that class. A property that defines that which possesses it.” But not all categories have a clear defining characteristic, and for many categories a single characteristic will never suffice. Scientists can and do argue about which characteristics to include as defining, which are more important, and how to police the boundaries of that characteristic.

Continue Reading »

Jan

02

2024

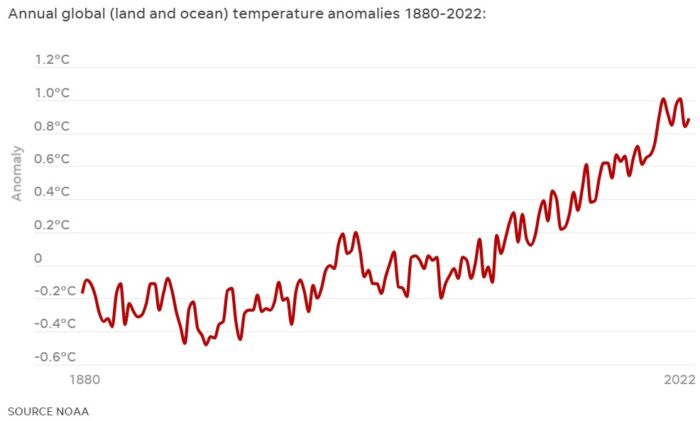

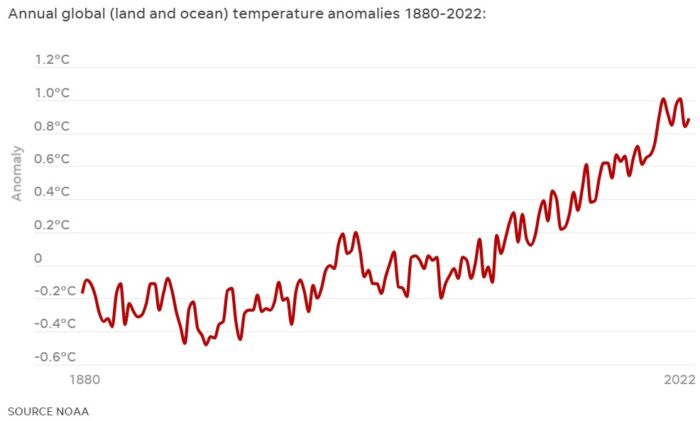

What everyone knew was coming is now official – 2023 was the warmest year on record. This means we can also say that the last 10 years are the hottest decade on record. 2023 dethrones 2016 as the previous warmest year and bumps 2010 out of the top 10. Further, in the last half of the year, many of the months were the hottest months on record, and by a large margin. September’s average temperature was 1.44 C above pre-industrial levels, beating the previous record set in 2020 of 0.98 C. The average for 2023 is 1.4 C, beating the previous record in 2016 of 1.2 C. This also makes 2023 probably the warmest year in the last 125,000 years.

What everyone knew was coming is now official – 2023 was the warmest year on record. This means we can also say that the last 10 years are the hottest decade on record. 2023 dethrones 2016 as the previous warmest year and bumps 2010 out of the top 10. Further, in the last half of the year, many of the months were the hottest months on record, and by a large margin. September’s average temperature was 1.44 C above pre-industrial levels, beating the previous record set in 2020 of 0.98 C. The average for 2023 is 1.4 C, beating the previous record in 2016 of 1.2 C. This also makes 2023 probably the warmest year in the last 125,000 years.

There is no mystery as to why this is happening, and it’s exactly what scientists predicted would happen. Remember the global warming “pause” that was allegedly happening between 1998 and 2012? This was the pause that never was, a short term fluctuation in the long term trend and a bit of statistical voodoo. Global warming deniers were declaring that global warming was over, it was never real, it was just a statistical fluke and the world was regressing back to the mean. Meanwhile, scientists said the long term trend had not altered and predicted the next decade would be even warmer. In retrospect, it turns out that during the alleged “pause” more heat was going into the oceans and was not fully reflected in surface temperatures.

The best test of a scientific hypothesis is its ability to make predictions about future data. The deniers were predicting that the Earth would simply return to baseline temperatures, while the scientific community were united in predicting that the next decade (now the past decade) would see continued warming.

Continue Reading »

It is now generally accepted that 66 million years ago a large asteroid smacked into the Earth, causing the large Chicxulub crater off the coast of Mexico. This was a catastrophic event, affecting the entire globe. Fire rained down causing forest fires across much of the globe, while ash and debris blocked out the sun. A tsunami washed over North America – one site in North Dakota contains fossils from the day the asteroid hit, including fish with embedded asteroid debris. About 75% of species went extinct as a result, including all non-avian dinosaurs.

It is now generally accepted that 66 million years ago a large asteroid smacked into the Earth, causing the large Chicxulub crater off the coast of Mexico. This was a catastrophic event, affecting the entire globe. Fire rained down causing forest fires across much of the globe, while ash and debris blocked out the sun. A tsunami washed over North America – one site in North Dakota contains fossils from the day the asteroid hit, including fish with embedded asteroid debris. About 75% of species went extinct as a result, including all non-avian dinosaurs.

The topic of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) is a great target for science communication because public attitudes have largely been shaped by deliberate misinformation, and the research suggests that those attitudes can change in response to more accurate information. It is the topic where the disconnect between scientists and the public is the greatest, and it is the most amenable to change.

The topic of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) is a great target for science communication because public attitudes have largely been shaped by deliberate misinformation, and the research suggests that those attitudes can change in response to more accurate information. It is the topic where the disconnect between scientists and the public is the greatest, and it is the most amenable to change. Have you memorized yet what CRISPR stands for – clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats? Well, now you can add MOBE to the list – multiplexed orthogonal base editor. Base editors are not new, they are basically enzymes that will change one base – C (cytosine), T (thymine), G (guanine), A (adenosine) – in DNA to another one, so a C to a T or a G to an A. MOBE is a guided system for making multiple desired base edits at once.

Have you memorized yet what CRISPR stands for – clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats? Well, now you can add MOBE to the list – multiplexed orthogonal base editor. Base editors are not new, they are basically enzymes that will change one base – C (cytosine), T (thymine), G (guanine), A (adenosine) – in DNA to another one, so a C to a T or a G to an A. MOBE is a guided system for making multiple desired base edits at once. For decades scientists were confused by Antarctic sea ice. Climate models predict that it should be decreasing, and yet it has been steadily and slowly increasing. It also made for a great talking point for climate change deniers – superficially it seems like counter evidence to the global warming narrative, and at least paints scientists as if they don’t really know what’s going on.

For decades scientists were confused by Antarctic sea ice. Climate models predict that it should be decreasing, and yet it has been steadily and slowly increasing. It also made for a great talking point for climate change deniers – superficially it seems like counter evidence to the global warming narrative, and at least paints scientists as if they don’t really know what’s going on. The Egyptian pyramids, and especially the Pyramids at Giza, have fascinated people probably since their construction between 4700 and 3700 years ago. They are massive structures, and it boggles the mind that an ancient culture, without the benefit of any industrial technology, could have achieved such a feat. This has led to endless speculation, especially in modern times, that perhaps some lost advanced civilization was at work, or maybe aliens.

The Egyptian pyramids, and especially the Pyramids at Giza, have fascinated people probably since their construction between 4700 and 3700 years ago. They are massive structures, and it boggles the mind that an ancient culture, without the benefit of any industrial technology, could have achieved such a feat. This has led to endless speculation, especially in modern times, that perhaps some lost advanced civilization was at work, or maybe aliens. Bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria, are the most abundant form of life on Earth. And yet we know comparatively little about them. But in recent years phage research has taken off with renewed interest. This is partly driven by the availability of CRISPR-based tools for studying genomes. Interestingly, CRISPR itself is a gene-editing tool that derives from bacteria and archaea, which evolved the system as a defense against viruses that infect them and alter their genome. Now we are using CRISPR to investigate those very viruses, and perhaps use that knowledge as a tool to fight bacterial infections. Bacteria may have handed us the tools to fight bacteria.

Bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria, are the most abundant form of life on Earth. And yet we know comparatively little about them. But in recent years phage research has taken off with renewed interest. This is partly driven by the availability of CRISPR-based tools for studying genomes. Interestingly, CRISPR itself is a gene-editing tool that derives from bacteria and archaea, which evolved the system as a defense against viruses that infect them and alter their genome. Now we are using CRISPR to investigate those very viruses, and perhaps use that knowledge as a tool to fight bacterial infections. Bacteria may have handed us the tools to fight bacteria. Most people have watched large flocks of birds. They are fascinating, and have interested scientists for a long time. How, exactly, do so many birds maintain their cohesion as a flock? It’s obviously a dynamic process, but what are the mechanisms?

Most people have watched large flocks of birds. They are fascinating, and have interested scientists for a long time. How, exactly, do so many birds maintain their cohesion as a flock? It’s obviously a dynamic process, but what are the mechanisms? I love to follow kerfuffles between different experts and deep thinkers. It’s great for revealing the subtleties of logic, science, and evidence. Recently there has been an interesting online exchange between a physicists science communicator (

I love to follow kerfuffles between different experts and deep thinkers. It’s great for revealing the subtleties of logic, science, and evidence. Recently there has been an interesting online exchange between a physicists science communicator ( Categorization is critical in science, but it is also very tricky, often deceptively so. We need to categorize things to help us organize our knowledge, to understand how things work and relate to each other, and to communicate efficiently and precisely. But categorization can also be a hindrance – if we get it wrong, it can bias or constrain our thinking. The problem is that nature rarely cleaves in straight clean lines. Nature is messy and complicated, almost as if it is trying to defy our arrogant attempts at labeling it. Let’s talk a bit about how we categorize things, how it can go wrong, and why it matters.

Categorization is critical in science, but it is also very tricky, often deceptively so. We need to categorize things to help us organize our knowledge, to understand how things work and relate to each other, and to communicate efficiently and precisely. But categorization can also be a hindrance – if we get it wrong, it can bias or constrain our thinking. The problem is that nature rarely cleaves in straight clean lines. Nature is messy and complicated, almost as if it is trying to defy our arrogant attempts at labeling it. Let’s talk a bit about how we categorize things, how it can go wrong, and why it matters. What everyone knew was coming is now official – 2023 was the warmest year on record. This means we can also say that the last 10 years are the

What everyone knew was coming is now official – 2023 was the warmest year on record. This means we can also say that the last 10 years are the