Feb 21 2020

Binaural Beats, Mood and Memory

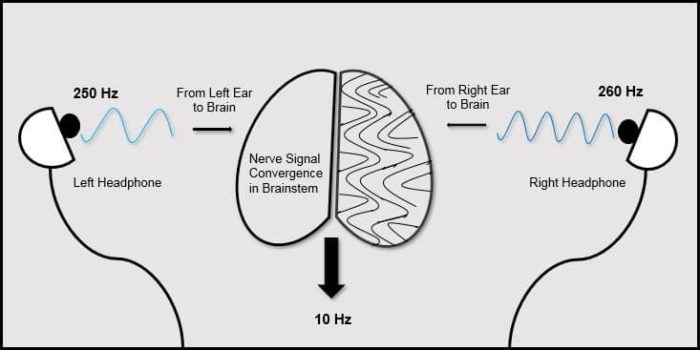

Binaural beats are an auditory illusion created by listening to two tones of slightly different frequency. This produces a type of feedback effect in the brain that produces a third illusory sound that has a pulsating quality, hence binaural beats. All perceptual illusions are fascinating, at least to neuroscientists, because they are clues to how the brain processes sensory information. What we ultimately perceive is the result of a complex constructive process (not passive recording) and understanding the process offers insight into the strengths and weaknesses of human perception.

Binaural beats are an auditory illusion created by listening to two tones of slightly different frequency. This produces a type of feedback effect in the brain that produces a third illusory sound that has a pulsating quality, hence binaural beats. All perceptual illusions are fascinating, at least to neuroscientists, because they are clues to how the brain processes sensory information. What we ultimately perceive is the result of a complex constructive process (not passive recording) and understanding the process offers insight into the strengths and weaknesses of human perception.

But there is another angle to binaural beats about which I have always been, appropriately, skeptical. There is popular belief that listening to the binaural beat illusion is a method for “hacking” into the brain and affecting mood and cognition, improving memory and alertness. Most “brain hack” claims turn out to be false, or at least massively overstated, so initial skepticism is warranted. Such claims are often based on, “Look, something is happening in the brain, therefore…” types of evidence. But the brain is a machine, albeit a biological one, and it is not impossible that outside stimulation can make the machine work more or less efficiently. So I filed this away as – a small effect is not impossible, but I would need to see convincing evidence before I believe this “one simple trick” claim.

There is a recent study of the effects of binaural beats which prompted this review, but this is just the latest in a couple of decades of research. Let’s first look at the most recent study – Binaural beats through the auditory pathway: from brainstem to connectivity patterns. The study looked at two things, the effect of binaural beats on the overall pattern of brain activity, and the effect on mood. What they found is discouraging for those who think binaural beats have some special effect on the brain. They found:

Here, we sought to address those questions in a robust fashion using a single-blind, active-controlled protocol. To do so, we compared the effects of binaural beats with a control beat stimulation (monaural beats, known to entrain brain activity but not mood) across four distinct levels in the human auditory pathway: subcortical and cortical entrainment, scalp-level Functional Connectivity and self-reports. Both stimuli elicited standard subcortical responses at the pure tone frequencies of the stimulus (i.e., Frequency Following Response), and entrained the cortex at the beat frequency (i.e., Auditory Steady State Response). Furthermore, Functional Connectivity patterns were modulated differentially by both kinds of stimuli, with binaural beats being the only one eliciting cross-frequency activity.

What this means is that when listening to sound, similar to when watching flashing lights at a specific frequency, there is brainwave activity that synchronizes with the stimulus. There is nothing special or surprising about this – this is just the brain responding to the stimulus. In this study the monaural beats had a stronger effect on this kind of synchronizing brain activity. What they used for the monaural beats was a recording of the two tones used to created the binaural beats illusions, but also included actual sounds of the third illusory tone. These same three tones were presented to both ears, so there was no illusory sound. This is a good model for the control, because the subject is hearing the same thing, just produced externally rather than internally.

However, the binaural beats also produced increased cross-frequency activity, meaning that different parts of the brain were communicating more with each other. Previous studies have found similar findings. We do not, however, really know the implications of this. This may be mostly just a manifestation of the illusion itself, and not produce any other effects. So of course we only see the brain activity that produces the illusion when the illusion is present. Again, we have to resist the temptation to say – look, stuff is happening, and then leap to conclusions from that simple fact.

The study also assessed the mood of the subjects by self report. Here they found no difference between the groups, so no effect from binaural beats on mood. There are some previous studies that show a possible effect on mood, which the current authors conclude may be just placebo effects. The authors conclude:

All in all, though binaural beats entrain cortical activity and elicit complex patterns of connectivity, the functional significance (if any) of binaural beats, and whether they are more “special” than monaural beats remain open questions.

That seems fair. However, this study did not look at the effects of binaural beats on memory or cognition, and that seems to be the most significant effect in the research so far. A 2019 meta-analysis concluded:

Our meta-analysis adds to the growing evidence that binaural-beat exposure is an effective way to affect cognition over and above reducing anxiety levels and the perception of pain without prior training, and that the direction and the magnitude of the effect depends upon the frequency used, time under exposure, and the moment in which the exposure takes place.

A meta-analysis has to be taken with a grain of salt, because they follow the GIGO principle – garbage in, garbage out. They also have a poor track record of predicting later definitive clinical trials. Essentially, you cannot take a bunch of preliminary studies and turn them into one big rigorous study. You will just be giving more statistical power to the research bias manifest in the preliminary studies. The effect size is also modest, characterized by the authors of this meta-analysis as “medium”. But there is some consistency of replication that I find interesting.

Specifically, multiple studies have found that binaural beats of a frequency in the 15-20 hz range has a positive effect on memory, while those in the lower frequencies of 5-10 hz had a negative or no effect on memory. You have to be cautious when studies look at multiple outcomes, because that affects the statistical significance and finding an isolated positive result can just be random noise in the data. But when the same pattern is seen on more than one study, that adds credibility to the results.

Applying my usual criteria to the claim that binaural beats improves memory, I would say the current research is suggestive but not definitive, genuinely warranting further research. Such claims become convincing when they not only replicate, but survive increasingly rigorous methodology, without suffering from the “decline effect” to either clinical or statistical insignificance. I also suspect that there may be a non-specific effect at work here, and at least this would need to be ruled out with careful controls. The question is, if there is a real memory-enhancing effect from specific frequencies of binaural beats, is that due to the increased cross-talk we are seeing in the brain, or is it rather due to a non-specific alerting effect from the stimuli itself? Might any stimulus that is sufficiently annoying or stimulating have the same effect?

This, in my opinion, is the critical question, assuming there is a real effect here at all. Are we really hacking the brain, or is this just a complicated way of producing a non-specific alerting effect? I often feel that researchers don’t go far enough in exploring this vital question, and prematurely conclude that there is something special about their intervention, with then leads to speculation about neuroscience which is misleading and counterproductive. For example, I think we are probably only seeing non-specific placebo-type effects from things like acupuncture, meditation, EMDR, and many types of “therapies”. And yet much ink is wasted speculating about specific explanations for these non-specific effects. These implausible speculations are then supported by evidence that amounts to – look, stuff is happening. Of course stuff is happening. The awake brain is always active and responding to stimuli.

In the end binaural beats are an interesting illusory phenomenon, that if nothing else has the potential to teach us something about brain function. Whether or not this phenomenon can be exploited as a therapeutic or enhancement intervention remains to be seen, and I hope we do see some high quality research that will be convincing either way.