Sep

29

2023

I know we are supposed to be worried about the world supply of fresh water. I have been hearing that at least for the last 40 years, and the statistics are alarming. According to the Global Commission on the Economics of Water:

I know we are supposed to be worried about the world supply of fresh water. I have been hearing that at least for the last 40 years, and the statistics are alarming. According to the Global Commission on the Economics of Water:

“We are seeing the consequences not of freak events, nor of population growth and economic development, but of having mismanaged water globally for decades. As the science and evidence show, we now face a systemic crisis that is both local and global.”

Sounds about right. We are not very good at this sort of large-scale management. Everyone just does their thing, oblivious to the big picture, until we have a crisis. Then experts point out the looming crisis which everyone at first ignores. Then we have meetings, summits, and a lot of hand-wringing but next to nothing gets done. Eventually we mostly technology our way out of the problem, but not after significant negative consequences, especially for the world’s poor. The water crisis seems to be following the same playbook.

Now experts are predicting that by 2030 world demand for fresh water will outstrip supply by 40%. This shortage will affect everyone, including people in wealthy developed nations. So now it’s a real crisis. To be clear, I am not trying to minimize this problem at all. The Commission outlines a seven-point plan for properly and fairly managing the world’s fresh water supply, and it all sound very reasonable. It feels like we are in a phase of human history when we are collectively realizing that billions of people have a global effect on the entire planet, and we need to seriously start transitioning from a local focus on securing resources, to globally managing those limited resources.

Continue Reading »

Sep

28

2023

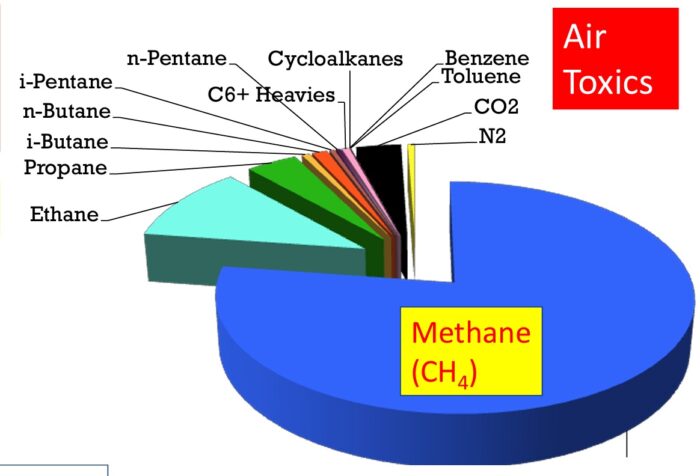

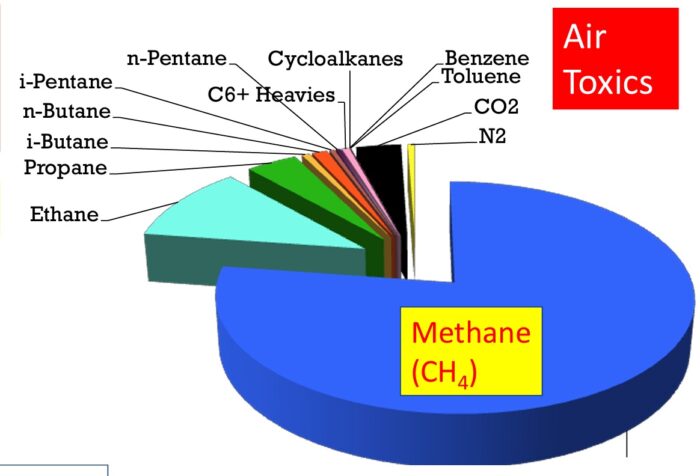

In the last 18 years, since 2005, the US has decreased our CO2 emissions due to electricity generation by 32%, 819 million metric tons of CO2 per year. Thirty percent of this decline can be attributed to renewable energy generation. But 65% is attributed to essentially replacing coal-fired plants with natural gas (NG) fired plants. The share of coal decreased from 50% to 23% while the share of NG increased from 19% to 38%. Burning coal for energy released about twice as much CO2 as burning NG. Plus, NG power plants are more efficient than coal. The net result is that NG releases about 30% of the CO2 per unit of energy created as does coal.

In the last 18 years, since 2005, the US has decreased our CO2 emissions due to electricity generation by 32%, 819 million metric tons of CO2 per year. Thirty percent of this decline can be attributed to renewable energy generation. But 65% is attributed to essentially replacing coal-fired plants with natural gas (NG) fired plants. The share of coal decreased from 50% to 23% while the share of NG increased from 19% to 38%. Burning coal for energy released about twice as much CO2 as burning NG. Plus, NG power plants are more efficient than coal. The net result is that NG releases about 30% of the CO2 per unit of energy created as does coal.

But – the picture is more complicated than just calculating CO2 release. The implications of a true comparison between these two sources of energy has huge implications for our attempts at reducing climate change. It’s clear that we should phase out all fossil fuels as quickly as possible. But this transition is going to take decades and cost trillions. Meanwhile, we are already skirting close to the line in terms of peak warming and the consequences of that warming. We no longer have the luxury of just developing low carbon technology with the knowledge that it will ultimately replace fossil fuels. The path we take to get to net zero matters. We need to take the path that lowers greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as quickly as possible. So when we build more wind, solar, nuclear, hydroelectric, and geothermal plants, do we shut down coal, natural gas, or perhaps it doesn’t matter?

If we look just at CO2, it’s a no-brainer – coal is much worse and we should prioritize shutting down coal-fired plants. This may still be the ultimate answer, but there is another factor to consider. NG contains methane, and methane is also a GHG. Per molecule, methane causes 80 times the warming of CO2 over a 20 year period. So any true comparison between coal and NG must also consider methane. (A little methane is also released in coal mining.) But considering methane is extremely complicated, and involves choices when looking at the data that don’t have any clear right or wrong answers.

Continue Reading »

Sep

21

2023

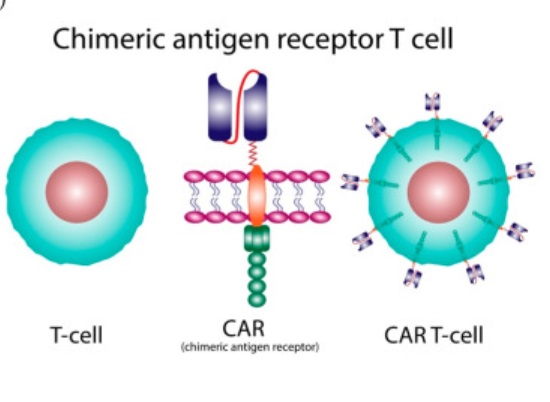

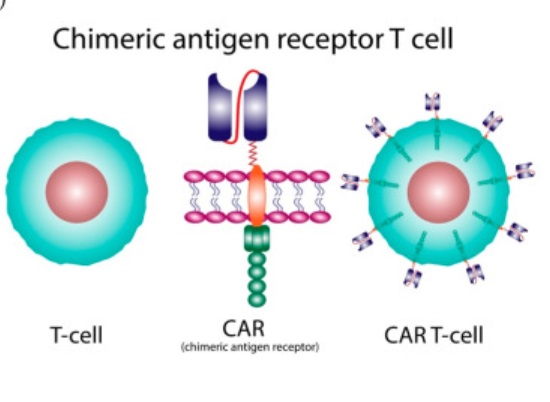

There is a recent medical advance that you may not have heard about unless you are a healthcare professional or encountered it from the patient side – CAR-T cell therapy. A recent study shows the potential for continued incremental advance of this technology, but already it is a powerful treatment.

There is a recent medical advance that you may not have heard about unless you are a healthcare professional or encountered it from the patient side – CAR-T cell therapy. A recent study shows the potential for continued incremental advance of this technology, but already it is a powerful treatment.

Like all technologies, the roots go back pretty far. It was first discovered that immune cells protect against cancer in 1960. In 1986 tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were used to attack cancer cells. In 1993 the first generation of genetically modified T-cells using the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) technique was developed. This technique fuses the business end of an antibody to a receptor on a T-cell (hence a chimera) which potentially targets that T-cell against whatever antigen the antibody targets. So you can make antibodies against a protein unique to a specific type of cancer, then fuse part of that antibody to T-cell receptors, put those T-cells back into the patient and they will potentially attack the cancer cells. This first generation CAR-T cells were not effective clinically because they did not survive long enough in the body to work.

In 1998 it was discovered that adding a costimulatory domain (CD28) to the CAR allowed it to persist longer in the body, creating the potential for clinical treatment. In 2002 this technique was used to develop second generation CAR-T cells that were shown for the first time to fight cancer in mice (the first study was of prostate cancer). Then in 2003 CAR-T cells using CD19 instead of CD28 were developed, and found to be more effective. In 2013 the first clinical trial in humans showing efficacy of CAR-T therapy in cancer (leukemia) was published, starting the era of using CAR-T therapy in treating blood cancers. The first CAR-T base treatment was approved by the FDA in 2017.

Over the last 8 years CAR-T therapy has become standard treatment for blood-born cancers (lymphoma and acute lymphoblastic leukemia). T-cells are taken from patients with cancer, they are then genetically modified into CAR-T cells, reproduced to make lots of them, and then given back to the patient to fight their cancer. In the last decade scientific advance has continued, with research targeting other proteins to potentially fight solid tumors. In 2017 scientists starting using CRISPR technology to make their CAR-T cells allowing greater control and improved function.

Continue Reading »

Sep

18

2023

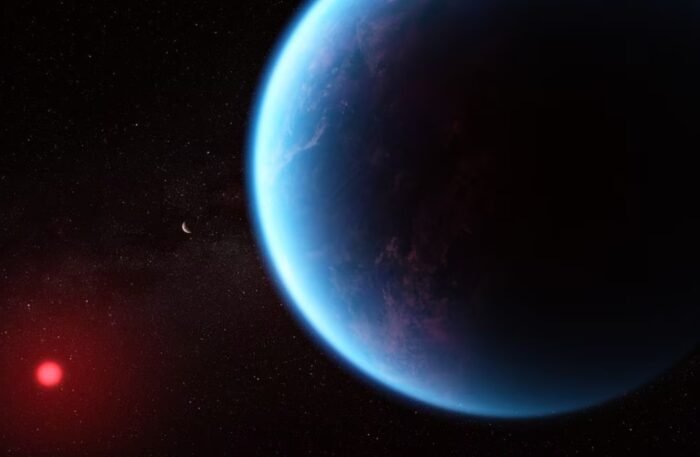

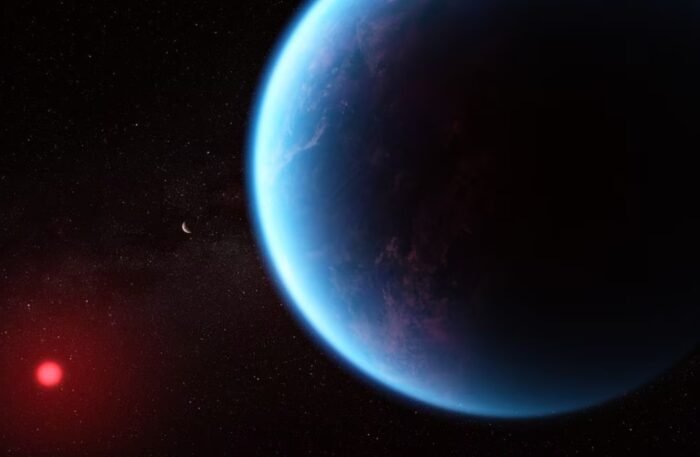

The James Webb Space Telescope spectroscopic analysis of K2-18b, an exoplanet 124 light years from Earth, shows signs that the atmosphere may contain dimethyl sulphide (DMS). This finding is more impressive when you know that DMS on Earth is only produced by living organisms, not by any geological process. The atmosphere of K2-18b also contains methane and CO2, which could be compatible with liquid water on the surface. Methane is also a possible signature of life, but it can also be produced by geological processes. This is pretty exciting, but the astronomers caution that this is a preliminary result. It must be confirmed by more detailed analysis and observation, which will likely take a year.

The James Webb Space Telescope spectroscopic analysis of K2-18b, an exoplanet 124 light years from Earth, shows signs that the atmosphere may contain dimethyl sulphide (DMS). This finding is more impressive when you know that DMS on Earth is only produced by living organisms, not by any geological process. The atmosphere of K2-18b also contains methane and CO2, which could be compatible with liquid water on the surface. Methane is also a possible signature of life, but it can also be produced by geological processes. This is pretty exciting, but the astronomers caution that this is a preliminary result. It must be confirmed by more detailed analysis and observation, which will likely take a year.

According to NASA:

K2-18 b is a super Earth exoplanet that orbits an M-type star. Its mass is 8.92 Earths, it takes 32.9 days to complete one orbit of its star, and is 0.1429 AU from its star. Its discovery was announced in 2015.

This planet was discovered with the transit method, so we have some idea of its radius and therefore density. It’s surface gravity is likely about 12 m/s^2 (Earth’s is 9.8). It has a hydrogen-rich atmosphere, which would explain the methane without the need for life. It orbits a red dwarf, and is likely tidally locked, or in a tidal resonance orbit. It receives an amount of radiation from its star similar to Earth. The big question – is K2-18 b potentially habitable?

Continue Reading »

Sep

12

2023

Here is a relatively simple math problem: A bat and a ball cost $1.10 combined. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? (I will provide the answer below the fold.)

Here is a relatively simple math problem: A bat and a ball cost $1.10 combined. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? (I will provide the answer below the fold.)

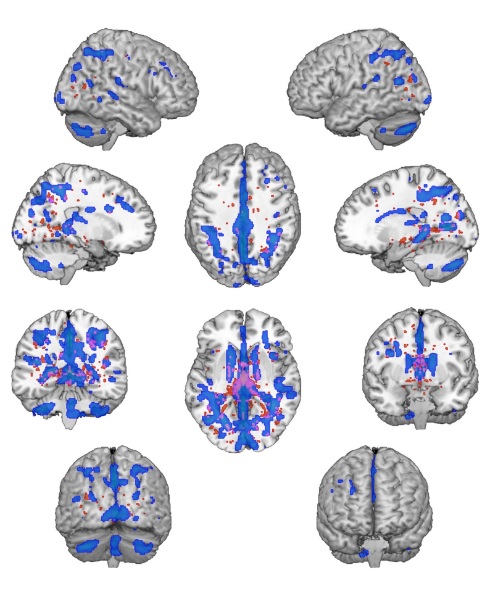

This problem is the basis of a large psychological literature on thinking systems in the human brain, discussed in Daniel Kahneman’s book: Thinking, Fast and Slow. The idea is that there are two parallel thinking systems in the brain, a fast intuitive system that provides quick answers which may or may not be strictly true, and a slow analytical system that will go through a problem systematically and check the results.

This basic scheme is fairly well established in the research literature, but there are many sub-questions. For example – what is the exact nature of the intuition for any particular problem? What is the interaction between the fast and slow system? What if multiple intuitions come into conflict by giving different answers to the same problem? Is it really accurate to portray these different thinking styles as distinct systems? Perhaps we should consider them subsystems, since they are ultimately part of the same singular mind. Do they function like subroutines in a computer program? How can we influence the operations or interaction of these subroutines with prompting?

A recent publication present multiple studies with many subjects addressing these subquestions. If you are interested in this question I suggest reading the original article in full. It is fairly accessible. But here is my overview. Continue Reading »

Sep

11

2023

I will acknowledge up front that I never drink, ever. The concept of deliberately consuming a known poison to impair the functioning of your brain never appealed to me. Also, I am a bit of a supertaster, and the taste of alcohol to me is horrible – it overwhelms any other potential flavors in the drink. But I am also not judgmental. I understand that most people who consume alcohol do so in moderation without demonstrable ill effects. I also know I am in the minority when it comes to taste.

I will acknowledge up front that I never drink, ever. The concept of deliberately consuming a known poison to impair the functioning of your brain never appealed to me. Also, I am a bit of a supertaster, and the taste of alcohol to me is horrible – it overwhelms any other potential flavors in the drink. But I am also not judgmental. I understand that most people who consume alcohol do so in moderation without demonstrable ill effects. I also know I am in the minority when it comes to taste.

But we do need to recognize that alcohol, like many other substances of abuse like cocaine, has the ability to be addictive, and can result in alcohol use disorder. Excessive alcohol use costs the US economy $249 billion per year from health care costs, lost productivity, traffic accidents, and criminal justice system costs. It dwarfs all other addictive substances combined. It is also well established that long term, excessive alcohol use reduces cognitive function.

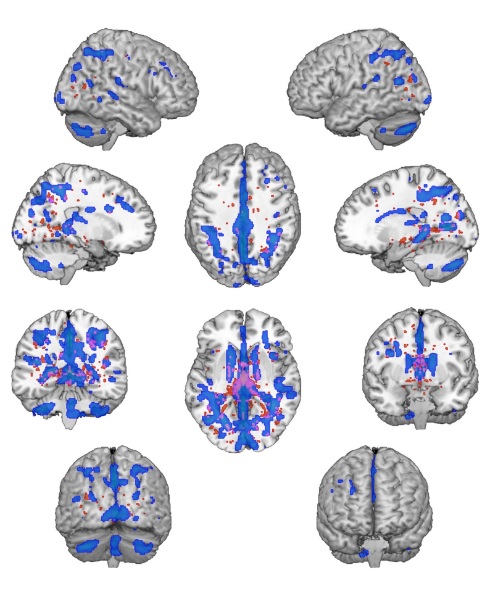

Recent research has explored the question of exactly what the effects of addictive substances are on the brain with chronic use. One of the primary effects appears to be on cognitive flexibility. In general terms this neurological function is exactly what it sounds like – flexibility in thinking and behavior. But researchers always need a way to operationalize such concepts – how do we measure it? There are two basic ways to operationalize cognitive flexibility – set shifting and task switching. Set shifting involves change the rules of how to accomplish a task, while task switching involves changes to a different task altogether.

For example, a task switching test might involve sorting objects that are of different shapes, colors, textures, and sizes. First subjects may be told to sort by colors, but also they are to respond to a specific cue (such as a light going on) by switching to sorting by shape. The test is – how quickly and effectively can a subject switch tasks like this? How many sorting mistakes will they make after switching tasks? Set shifting, on the other hand, changes the rules rather than the task – push the button every time the red light comes on, vs the green light.

Continue Reading »

Sep

08

2023

There is a lot of social psychology out there providing information that can inform our everyday lives, and most people are completely unaware of the research. Richard Wiseman makes this point in his book, 59 Seconds – we actually have useful scientific information, and yet we also have a vast self-help industry giving advice that is completely disconnected from this evidence. The result is that popular culture is full of information that is simply wrong. It is also ironically true that it many social situations our instincts are also wrong, probably for complicated reasons.

There is a lot of social psychology out there providing information that can inform our everyday lives, and most people are completely unaware of the research. Richard Wiseman makes this point in his book, 59 Seconds – we actually have useful scientific information, and yet we also have a vast self-help industry giving advice that is completely disconnected from this evidence. The result is that popular culture is full of information that is simply wrong. It is also ironically true that it many social situations our instincts are also wrong, probably for complicated reasons.

Let’s consider gift-giving, for example. Culture and intuition provide several answers as to what constitutes a good gift, which we can define as the level of gratitude and resulting happiness on the part of the gift recipient. We can also consider a secondary, but probably most important, outcome – the effect on the relationship between the giver and receiver. There is also the secondary effect of the satisfaction of the gift giver, which depends largely on the gratitude expressed by the receiver.

When considering what makes a good gift, people tend to focus on a few variables, reinforced by cultural expectations – the gift should be a surprise, it should provoke a big reaction, it should be unique, and more expensive gifts should evoke more gratitude. But it turns out, none of these things are true.

A recent study, for example, tried to simulate prior expectations on gift giving and found no significant effect on gratitude. These kinds of studies are all constructs, but there is a pretty consistent signal in the research that surprise is not an important factor to gift-giving. In fact, it’s a setup for failure. The gift giver has raised expectations of gratitude because of the surprise factor, and is therefore likely to be disappointed. The gift-receiver is also less likely to experience happiness from receiving the gift if the surprise comes at the expense of not getting what they really want. You would be far better off just asking the person what they want, or giving them something you know that they want and value rather than rolling the dice with a surprise. To be clear, the surprise factor itself is not a negative, it’s just not really a positive and is a risk.

Continue Reading »

Sep

07

2023

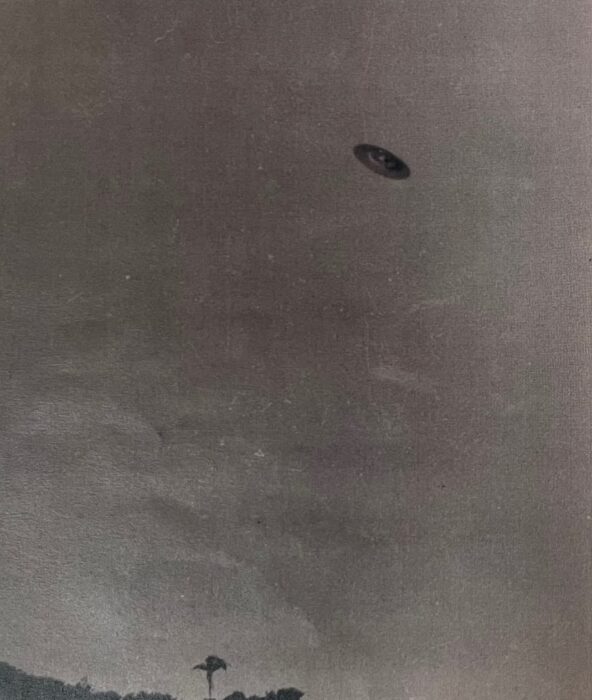

Nothing about the recent resurgence in interest in UFOs (now called UAPs for unidentified anomalous phenomena) is really new. It’s basically the same stories with the same level of completely unconvincing evidence. But what is somewhat new is the level of credulity and outright journalistic fail with which the mainstream media is reporting the story. I’m not talking about fringe media or local news but major news outlets. Take this recent article in the Washington Post, for example.

Nothing about the recent resurgence in interest in UFOs (now called UAPs for unidentified anomalous phenomena) is really new. It’s basically the same stories with the same level of completely unconvincing evidence. But what is somewhat new is the level of credulity and outright journalistic fail with which the mainstream media is reporting the story. I’m not talking about fringe media or local news but major news outlets. Take this recent article in the Washington Post, for example.

The main point of the article is that in the US information about UAPs is often classified, but this is not the case in many other countries. Author Terrence McCoy then focuses on Brazil, telling some of the UAP stories that have come out of this country. McCoy breathlessly tells these stories without capturing the real context here, missing the significance of his own premise. He begins:

Early one August evening in 1954, a Brazilian plane was tracked by an unidentified object of “strong luminosity” that didn’t appear on radar. Two decades later, a river community in the northern Amazon jungle was repeatedly visited by glowing orbs that beamed lights down onto the inhabitants. In 1986, more than 20 unidentified aerial phenomena lit up the skies over Brazil’s most populous states, sending the Brazilian air force out in pursuit.

The stories are not the ravings of a UFO buff. They are official assessments by Brazilian pilots and military officers — who often struggled to put into words what they’d seen — and can be found in Brazil’s remarkable historical archive of reported UFO visitations.

This pretty much sets the tone for the article. There is a reason the US is very protective of a lot of information that winds up in UAP reports – we have a vast intelligence and monitoring network. Our military and intelligence officers do not want other countries to know the details of that network – so often, what the government is hiding is not the content of the monitoring but the mere fact of our monitoring capability. Then, of course, throughout recent decades there have been many classified military systems, the kind that can create UAP sightings, and the government is not about to say – “That wasn’t an alien spacecraft, it was our new super secret spy plane.”

Continue Reading »

Sep

05

2023

Do birds of a feather flock together, or do opposites attract? These are both common aphorisms, which means that they are commonly offered as generally accepted truths, but also that they may by wrong. People like pithy phrases, so they spread prolifically, but that does not mean they contain any truth. Further, our natural instincts are not adequate to properly address whether they are true or not.

Do birds of a feather flock together, or do opposites attract? These are both common aphorisms, which means that they are commonly offered as generally accepted truths, but also that they may by wrong. People like pithy phrases, so they spread prolifically, but that does not mean they contain any truth. Further, our natural instincts are not adequate to properly address whether they are true or not.

Often people will resort to the “availability heuristic” when confronted with these types of claims. If they can readily think of an example that seems to support the claim, then they accept it as probably true. We use the availability of an example as a proxy for data, but it’s a very bad proxy. What we really need to address such questions is often statistics, something which is not very intuitive for most people.

Of course, that’s where science comes in. Science is a formal system we use to supplement our intuition, to come to more reliable conclusions about the nature of reality. Recently researchers published a very large review of data, a meta-analysis, combined with a new data analysis to address this very question. First, we need operationalize the question, to put it in a form that is precise and amenable to objective data. If we look at couples, how similar or different are they? To get even more precise, we need to identify specific traits that can be measured or quantified in some way and compare them.

Continue Reading »

I know we are supposed to be worried about the world supply of fresh water. I have been hearing that at least for the last 40 years, and the statistics are alarming. According to the Global Commission on the Economics of Water:

I know we are supposed to be worried about the world supply of fresh water. I have been hearing that at least for the last 40 years, and the statistics are alarming. According to the Global Commission on the Economics of Water:

In the last 18 years, since 2005, the US has

In the last 18 years, since 2005, the US has  There is a recent medical advance that you may not have heard about unless you are a healthcare professional or encountered it from the patient side – CAR-T cell therapy.

There is a recent medical advance that you may not have heard about unless you are a healthcare professional or encountered it from the patient side – CAR-T cell therapy.  The James Webb Space Telescope spectroscopic analysis of K2-18b, an exoplanet 124 light years from Earth, shows

The James Webb Space Telescope spectroscopic analysis of K2-18b, an exoplanet 124 light years from Earth, shows  Here is a relatively simple math problem: A bat and a ball cost $1.10 combined. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? (I will provide the answer below the fold.)

Here is a relatively simple math problem: A bat and a ball cost $1.10 combined. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? (I will provide the answer below the fold.) I will acknowledge up front that I never drink, ever. The concept of deliberately consuming a known poison to impair the functioning of your brain never appealed to me. Also, I am a bit of a

I will acknowledge up front that I never drink, ever. The concept of deliberately consuming a known poison to impair the functioning of your brain never appealed to me. Also, I am a bit of a  There is a lot of social psychology out there providing information that can inform our everyday lives, and most people are completely unaware of the research. Richard Wiseman makes this point in his book, 59 Seconds – we actually have useful scientific information, and yet we also have a vast self-help industry giving advice that is completely disconnected from this evidence. The result is that popular culture is full of information that is simply wrong. It is also ironically true that it many social situations our instincts are also wrong, probably for complicated reasons.

There is a lot of social psychology out there providing information that can inform our everyday lives, and most people are completely unaware of the research. Richard Wiseman makes this point in his book, 59 Seconds – we actually have useful scientific information, and yet we also have a vast self-help industry giving advice that is completely disconnected from this evidence. The result is that popular culture is full of information that is simply wrong. It is also ironically true that it many social situations our instincts are also wrong, probably for complicated reasons. Nothing about the recent resurgence in interest in UFOs (now called UAPs for unidentified anomalous phenomena) is really new. It’s basically the same stories with the same level of completely unconvincing evidence. But what is somewhat new is the level of credulity and outright journalistic fail with which the mainstream media is reporting the story. I’m not talking about fringe media or local news but major news outlets.

Nothing about the recent resurgence in interest in UFOs (now called UAPs for unidentified anomalous phenomena) is really new. It’s basically the same stories with the same level of completely unconvincing evidence. But what is somewhat new is the level of credulity and outright journalistic fail with which the mainstream media is reporting the story. I’m not talking about fringe media or local news but major news outlets.  Do birds of a feather flock together, or do opposites attract? These are both common aphorisms, which means that they are commonly offered as generally accepted truths, but also that they may by wrong. People like pithy phrases, so they spread prolifically, but that does not mean they contain any truth. Further, our natural instincts are not adequate to properly address whether they are true or not.

Do birds of a feather flock together, or do opposites attract? These are both common aphorisms, which means that they are commonly offered as generally accepted truths, but also that they may by wrong. People like pithy phrases, so they spread prolifically, but that does not mean they contain any truth. Further, our natural instincts are not adequate to properly address whether they are true or not.