Jan 19 2024

Why Do Species Evolve to Get Bigger or Smaller

Have you heard of Cope’s Rule or Foster’s Rule? American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope first noticed a trend in the fossil record that certain animal lineages tend to get bigger over evolutionary time. Most famously this was noticed in the horse lineage, beginning with small dog-sized species and ending with the modern horse. Bristol Foster noticed a similar phenomenon specific to islands – populations that find their way to islands tend to either increase or decrease in size over time, depending on the availability of resources. This may also be called island dwarfism or gigantism (or insular dwarfism or gigantism).

Have you heard of Cope’s Rule or Foster’s Rule? American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope first noticed a trend in the fossil record that certain animal lineages tend to get bigger over evolutionary time. Most famously this was noticed in the horse lineage, beginning with small dog-sized species and ending with the modern horse. Bristol Foster noticed a similar phenomenon specific to islands – populations that find their way to islands tend to either increase or decrease in size over time, depending on the availability of resources. This may also be called island dwarfism or gigantism (or insular dwarfism or gigantism).

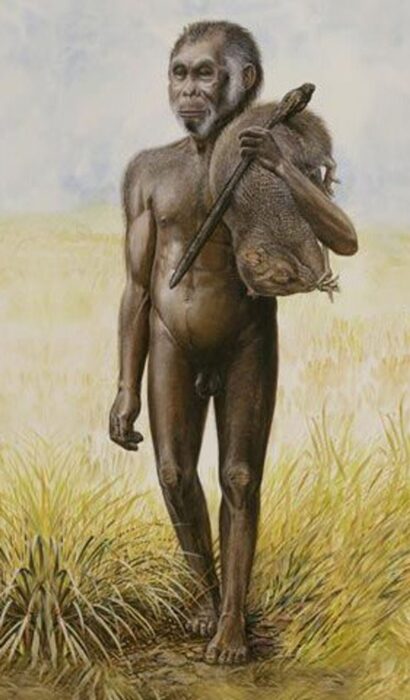

When both of these things happen in the same place there can be some interesting results. On the island of Flores a human lineage, Homo floresiensis (the Hobbit species) experienced island dwarfism, while the local rats experienced island gigantism. The result were people living with rats the relative size of large dogs.

Based on these observations, two questions emerge. The first (and always important and not to be skipped) is – are these trends actually true or are the initial observations just quirks or hyperactive pattern recognition. For example, with horses, there are many horse lineages and not all of them got bigger over time. Is this just cherry-picking to notice the one lineage that survived today as modern horses? If some lineages are getting bigger and some are getting smaller, is this just random evolutionary change without necessarily any specific trend? I believe this question has been answered and the consensus is that these trends are real, although more complicated than first observed.

This leads to the second question – why? We have to go beyond just saying “evolutionary pressure” to determine if there is any unifying specific evolutionary pressure that is a dominant determinant of trends in body size over time. Of course, it’s very likely that there isn’t one answer in every case. Evolution is complex and contingent, and statistical trends in evolution over time can emerge from many potential sources. But we do see these body size trends a lot, and it does suggest there may be a common factor.

Also, the island dwarfism/gigantism thing seems to be real, and the fact that these trends correlate so consistently with migrating to an island suggests a common evolutionary pressure. Foster, who published his ideas in 1964, thought it was due to resources. Species get smaller if island resources are scarce, or they get bigger if island resources are abundant due to relative lack of competition. Large mainland species who find themselves on islands may find a smaller region in which to operate which much less resources, so the smaller critters will have an advantage. Also, smaller species can have a shorter gestation time and more rapid generational time, which can provide advantages in a stressed environment. Predator species may then become smaller in order to adapt to smaller prey (which apparently is also a thing).

At the small end of the animal size, getting bigger has advantages. Larger animals can go longer between meals and can roam across a larger range looking for food. Again, this is what we see, the largest animals become smaller and the smallest animals become larger, meeting in the middle (hence the Hobbits with dog-sized rats).

Now a recent study looks that these ideas with computer evolutionary simulations. The simulations pretty much confirm what I summarized above but also add some new wrinkles. The simulations show that a key factor, beyond the availability of resources, is competition for those resources. First, it showed a general trend in increasing body size due to competition between species. When different species compete in the same niche the larger animals tend to win out. They state this as Cope’s rule applying when interaction between species is determines largely by their body size.

The simulations also showed, however, that when the environment is stress the larger species were more vulnerable to extinction. There were relatively fewer individuals in larger species with long gestation and generational times. While smaller species could weather the strain better and bounce back quicker, but then they subsequently undergo slow increase in size when the environment stabilizes. This leads to what they call recurrent Cope’s Rule – each subsequent pulse of gigantism gets even bigger.

The simulations also confirmed island dwarfism – that species tend to shrink over time when there is overlap in niches and resource use, which contributes to a decreased resource availability. They call this an inverse Cope’s Rule. They don’t refer to Foster’s Rule, I think because the simulations were independent of being on an island or in an insular environment (which is the core of Foster’s observation). Rather, species become smaller when their interaction is determined more by the environment and resource availability than their relative body size (which could be the case on islands).

So the simulations don’t really change anything dramatically. They largely confirm Cope’s Rule and Foster’s Rule, and add the layer that niche overlap and competition is important, not just total availability of recourses.