Jul 10 2017

Why Are We Conscious?

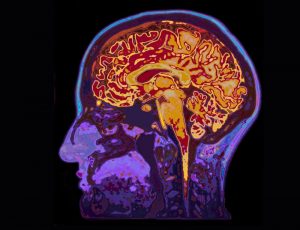

While we are still trying to sort out exactly what processes and networks in the brain create consciousness, we are also still uncertain why we are conscious in the first place. A new study tries to test one hypothesis, but before we get to that let’s review the problem.

While we are still trying to sort out exactly what processes and networks in the brain create consciousness, we are also still uncertain why we are conscious in the first place. A new study tries to test one hypothesis, but before we get to that let’s review the problem.

The question is – what is the evolutionary advantage, if any, of our subjective experience of our own existence? Why do we experience the color red, for example – a property philosophers of mind call qualia?

One answer is that consciousness is of no specific benefit. David Chalmers imagined philosophical zombies (p-zombies) who could do everything humans do but did not experience their own existence. A brain could process information, make decisions, and engage in behavior without actual conscious awareness, therefore why does the conscious awareness exist?

This idea actually goes back to soon after Darwin proposed his theory of evolution. In 1874 T.H. Huxley wrote an essay called, “On the Hypothesis that Animals are Automata.” In it he argued that all animals, including humans, are automata, meaning their behavior is determined by reflex action only. Humans, however, were “conscious automata” – consciousness, in his view, was an epiphenomenon, something that emerged from brain function but wasn’t critical to it. Further he argued that the arrow of cause and effect led only from the physical to the mental, not the other way around. So consciousness did nothing. We are all just passengers experiencing an existence that carries on automatically.

I reject both Chalmers’ and Huxley’s notions. There are many good hypotheses as to what benefit consciousness can provide. Even the most primitive animals have some basic system of pleasure and pain, stimuli that attract them and stimuli that repel them. Vertebrates evolved much more elaborate systems, including the complex array of emotions we experience. In more complex animals the point of such emotions is to provide motivation to either engage in or avoid certain behaviors. Often different emotions conflict and we need to resolve or balance the conflict. Consciousness would seem to be an advantage for such complicated motivational reasoning. Terror is a good way to get an animal to marshal all of their resources to flee a predator.

Problem solving could also benefit from the ability to imagine possible solutions, to remember the outcome of prior attempts, and to make adjustments and also come up with creative solutions.

Consciousness might also help us distinguish a memory from a live experience. They are both very similar, activating the same networks in the brain, but they “feel” different. Consciousness may help us stay in the moment while accessing memories without confusing the two.

Attention is another critical neurological function in which it seems consciousness could be an advantage. We are overwhelmed with sensory input and the monitoring of internal states and memories. We actually use a great deal of brain function just deciding where to focus our attention and then filtering out everything else (while still maintaining a minimal alert system for danger). The phenomena of consciousness and attention are intimately intertwined and it may just not be possible to have the latter without the former.

Some have argued that consciousness also helps us synthesize sensory information, so that when we experience an event the sights and sounds are all stitched together and tweaked to form one seamless experience.

And finally we get to the hypothesis addressed by the current study – that consciousness allows for faster adaptation and learning (which would certainly be an adaptive advantage). In their study, Travers, Firth, and Shea compared adaption to conscious vs subliminal information. Subjects viewed a computer screen in which they were first prompted with a “X” in the middle of the screen. This was then replaced by arrows pointing either to the left or the right. In one group the arrows would stay on the screen for 33 ms, in the other for 400 ms. The shorter duration is not long enough to register consciously, but previous experiments have shown it is enough to respond unconsciously. The longer time is long enough for conscious awareness.

After the arrows then an “X” would appear either on the left side or the right side of the screen, and the subjects had to quickly identify which side. When the arrows pointed in the opposite direction to the eventual side of the X this introduced a short delay in response time, even when the arrows lingered for only 33 ms. The subjects had to mentally adjust for the conflicting information.

The results show that the group exposed to the 400 ms arrows, and were therefore conscious of their presence, were able to adapt to misinformation and increase their response time, while the 33 ms group were not. The conscious exposure group was also able to experiment with a variety of strategies to deal with the misinformation until they hit upon the best solution.

In other words, when the subjects were consciously aware of the incongruent information they were better able to adapt and learn to deal with it. Subjects were not able to adapt to the unconscious information.

This is an interesting experiment with a provocative result. Of course, with these types of experiments it is difficult to impossible to draw firm conclusions from a single study. The subject matter is extremely complex and it takes many experiments to account for all variables. There may also be other differences in how we process 33 ms information vs 400 ms other than conscious awareness. But the researchers did come up with a way to specifically test their hypothesis.

I don’t think this answers the question, why are we conscious? Perhaps all of the factors I outlined above are important, and there may be others. It does provide preliminary support for the notion that there are potential advantages to conscious awareness over the subconscious processing of information, at least in some situations.

And to be clear, our brains engage simultaneously in conscious and subconscious processing of information which both affect our behavior. Both are important and have different advantages and disadvantages. In fact, we have been learning more in the last few decades about how extensive and important subconscious processing is. The two kinds of information processing work together to create the final result of human thought and behavior.

It is also interesting to consider the parallels in artificial intelligence technology. We have been discovering how powerful AI systems without consciousness can be. In fact it seems that AI systems will be able to do much more than we previously imagined without a conscious layer to them at all. It will be interesting to see what kinds of limits we run into, and if it will ever be necessary to add a conscious layer in order to achieve certain functionality.

But we have to be aware also that computers are different from brains. Brains evolved and had to work with the material at hand. Perhaps consciousness was an available solution to the needs of complex adaptation and learning. It may not be the only one, however. We can top-down design computers without constraint. There are also things that silicon does better than biology, and we may leverage that in ways not available to organic brains.

I suspect a lot will depend on what we want the AI systems to do. But it seems for now they will be able to do what we want, such as drive cars, without the need for conscious awareness.