Sep 21 2020

The Holocaust and Losing History

In the movie Interstellar, which takes place in a dystopian future where the Earth is challenged by progressive crop failures, children are taught in school that the US never went to the Moon, that it was all a hoax. This is a great thought experiment – could a myth, even a conspiracy theory, rise to the level of accepted knowledge? In the context of religion the answer is, absolutely. We have seen this happen in recent history, such as with Scientology, and going back even a little further with Mormonism and Christian Science. But what is the extent of the potential contexts in which a rewriting of history within a culture can occur? Or, we can frame the question as – are there any limits to such rewriting of history?

In the movie Interstellar, which takes place in a dystopian future where the Earth is challenged by progressive crop failures, children are taught in school that the US never went to the Moon, that it was all a hoax. This is a great thought experiment – could a myth, even a conspiracy theory, rise to the level of accepted knowledge? In the context of religion the answer is, absolutely. We have seen this happen in recent history, such as with Scientology, and going back even a little further with Mormonism and Christian Science. But what is the extent of the potential contexts in which a rewriting of history within a culture can occur? Or, we can frame the question as – are there any limits to such rewriting of history?

I think it is easy to make a case for the conclusion that there are no practical limits. Religion is also not the only context in which myth can become belief. The more totalitarian the government, the more they will be able to rewrite history any way they want (“We’ve always been at war with Eastasia”). It is also standard belief, and I think correctly, that the victors write the history books, implying that they write it from their perspective, with themselves as the heroes and the losers as the villains.

But what about just culture? I think the answer here is an unqualified yes also. In many Asian cultures belief in chi, a mysterious life force, is taken for granted, for example. There are many cultural mythologies, stories we tell ourselves and each other that become accepted knowledge. These can be the hardest false beliefs to challenge in oneself, because they become part of your identity. Doubting these stories is equivalent to tearing out a piece of yourself, questioning your deeper world-view.

These cultural beliefs can also be weaponized, for political purposes, and for just marketing. A century ago Chairman Mao decided to manufacture a new history of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). He took parts of various previous TCM traditions, even ones that were mutually exclusive and at ideological war with each other, and then grafted them into a new TCM, altering basic concepts to make them less barbaric and more palatable to a modern society. Now, less than a century later, nearly everyone believes this manufactured fiction as if it were real history. Only skeptical nerds or certain historians know, for example, that acupuncture as practiced today is less than a century old, and not the thousands of years old that proponents claim. Mao’s propaganda has become history.

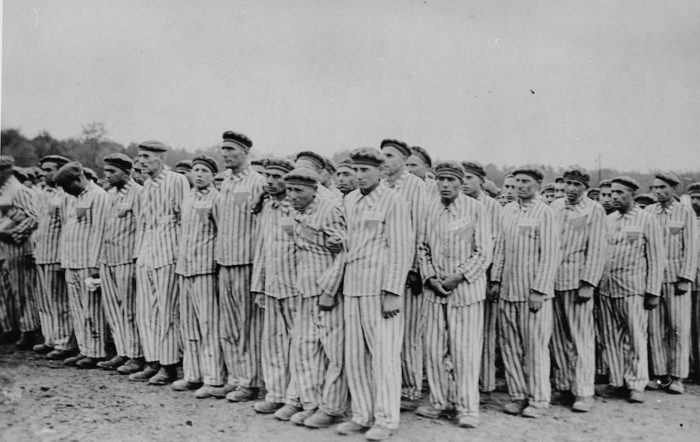

What about in the post-social media era? The internet was supposed to increase access to information to the masses, and it has. But it has also been a boon for misinformation, for spreading alternate narratives, conspiracy theories, and rewriting history for various purposes. What will the net effect be? It’s too early to tell, although there are lots of warning bells going off. One topic that has acted as a canary in the coal mine of knowledge of recent history is the Holocaust, referring to the Jewish Holocaust of World War II. Measuring people’s knowledge and beliefs about this recent history, especially young people who did not live through it, might tell us a lot about our educational system and how people form their beliefs and acquire knowledge.

According to the study of millennial and Gen Z adults aged between 18 and 39, almost half (48%) could not name a single concentration camp or ghetto established during the second world war.

Almost a quarter of respondents (23%) said they believed the Holocaust was a myth, or had been exaggerated, or they weren’t sure. One in eight (12%) said they had definitely not heard, or didn’t think they had heard, about the Holocaust.

Nationally 63% of responders did not know that 6 million Jews were killed in the Holocaust. If you take three basic pieces of knowledge, knowing of the Holocaust itself, that 6 million Jews were killed, and being able to name a single concentration camp or ghetto, the numbers are abysmal. Going state by state the percentage of people who knew all three ranges from 17-42%. These numbers are fairly consistent with other surveys. In a 2020 Pew Research poll 84% of Americans (all ages, not just younger generations as the above survey) knew that the Holocaust had something to do with persecution of the Jews. But only 45% knew that about 6 million Jews were killed. Only 43% knew that Hitler became Chancellor of Germany through a democratic political process.

Breaking this down a bit, the numbers were higher for older adults, for adults with higher education, for those who were or knew someone Jewish, and for atheists and agnostics. This suggests that basic education is failing students when it comes to a major event in recent world history. If we go back a little further, to the Armenian Holocaust at the turn of the century, only 35% of Americans are aware this happened.

Belief in conspiracy theories is also historically high. Almost half of Americans believe that JFK was assassinated as part of a conspiracy. The question is, will this number be higher or lower in 100 years? Will distance from the event allow emotions to fade and for historians to teach what really happened, or will the conspiracy narrative predominate? Will it just become something everyone “knows” even though it is wrong, and only history nerds will be able to say, “Well, actually, the historical evidence indicates that Oswald was likely a lone shooter.” The truth will become party trivia for nerds.

This is actually happening now in the US with the history of slavery. For example, 41% of people in a recent survey believe that the civil war was about something other than slavery, when the historical record is clear that slavery was the driving issue. Recently Trump announced that he thinks the US should be engaged in “patriotic education.” He stated, “Children must be taught that America is “an exceptional, free and just nation, worth defending, preserving and protecting.” We know what this means in states that take this approach to education – white-washing the history of slavery.

Trump also stated, “This includes restoring patriotic education in our nation’s schools, where they are trying to change everything that we have learned.” But challenging what we have learned should be the goal of education. Challenging inherited narratives, unquestioned belief systems, narrow views of history, and political propaganda should be a primary goal of education (of course, appropriate to age). The alternative, even if your goals may seem good, is indoctrinating children into mythology and reducing their ability to think critically. I have to say, this happens across the political spectrum, but that does not mean it is equivalent in magnitude. We need to question all narratives, regardless of where they fall politically.

Further, I would argue that questioning our own history is patriotic. It is a critical mechanism of self-correction and improvement. Indoctrination is unpatriotic, especially in a nation that prides itself on freedom.