Jun 24 2019

Study on Visual Framing in the Presidential Debates

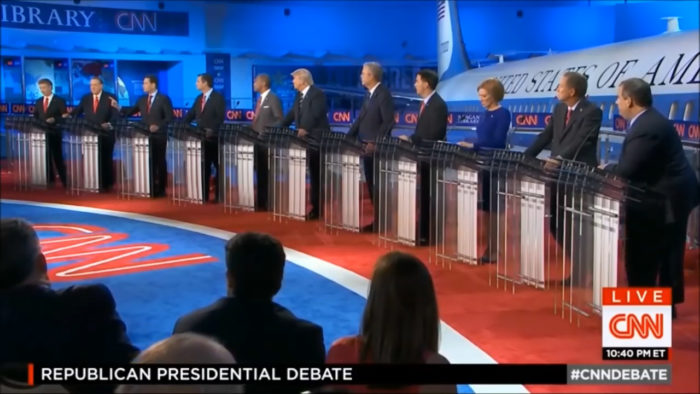

This week we will have the first primary debates of the presidential cycle, with two Democratic debates of the top 20 candidates (10 each night). A timely study was just published looking at the coverage of the different candidates in the 2016 primary debates of both parties. The results show a dramatic disparity in how different candidates were covered.

This week we will have the first primary debates of the presidential cycle, with two Democratic debates of the top 20 candidates (10 each night). A timely study was just published looking at the coverage of the different candidates in the 2016 primary debates of both parties. The results show a dramatic disparity in how different candidates were covered.

Unfortunately, the headline of the press release is misleading: Study Shows Visual Framing by Media in Debates Affects Public Perception. The study did not measure public perception, and therefore there is no basis to conclude anything about how the framing affected public perception. The study only quantified the coverage. But what they found was interesting.

They went frame by frame through the first two primary debates of both parties and calculated how much coverage each candidate had and what type – solo, split screen, side-by-side, multi-candidate shot, and audience reaction. This is what they found:

We likewise considered how much time the camera spent on a given candidate before cutting away by computing

-scores for each candidate’s mean camera fixation time (see Figure 3). This allowed us to see whether networks were visually priming the audience to differentially perceive the candidates as viable leaders. These data show that across the four debates, only Trump, specifically during CNN’s Republican Party debate, had substantially longer camera fixations (

) than the other candidates (

:

to 1.84). During this debate, Bush (

) was the only candidate besides Trump to have a positive z-score, providing modest support for our visual priming hypotheses concerning fixation time (H2). While for the Fox News debate, Cruz (

) and Huckabee (

) had substantially higher

-scores than the rest of the field, including Trump, their scores were well within the bounds of expectations. Likewise, on the Democratic side, neither CNN (

:

to 1.17) nor CBS (

:

to 0.89) gave a significant visual priming advantage to any candidate, although there were trends toward front-runners Clinton and Sanders having slightly longer than average fixation times during both debates.

Essentially, there was a lot of noise in the data, but only one significant spike above the noise – during the CNN debate Trump had significantly more camera time than the rest, with Bush also having greater camera time but not nearly as much as Trump. At the time they were the two front-runners in polling. Clinton and Sanders also had a trend towards more camera time in their debates, but not statistically significant.

As I said, you cannot make any cause and effect conclusions from this data. Trump was already the front-runner before he received preferential treatment. Also there are variables, such as who is physically placed next to whom, that will affect how often a candidate appears in shots with others. What this study does is raise the possibility that in a multi-candidate debate, subconscious (or perhaps conscious) choices by the producers can give differential treatment to the various candidates. The worry is that this will affect public perception. According to this data it would seem to reinforce the front-runners. This is obviously a tiny slice of the entire campaign process, but it does raise a deeper, and then a still deeper, question.

First – how do we optimize the campaign process to produce the “best” outcome? Of course, we have to define “best.” We cannot simply define it as the outcome we individually want. This can become a complicated question, but for starters I would say we would want the process to favor the more competent and virtuous candidates. We also want the process to be fair so that there is confidence in the democratic process itself, which means that candidates who reflect the goals, beliefs, priorities, and ideology of the greatest number of voters should tend to succeed. What we want to avoid is unintended perverse consequences in which candidates who have undesirable traits or who are on the political fringe have an unfair advantage.

Also, it seems to me that we want to avoid a system which dramatically reinforces existing popularity. We don’t want to just elect politicians who are famous for being famous. This cannot be avoided to some degree. Name recognition mostly drives polling (and raising money) early on. But we don’t want to reinforce that early popularity to such a degree that a highly competent mainstream but relatively unknown candidate can’t break in. That is what is worrying about this study – it shows a clear bias toward candidates who are already popular. The whole point of the debates is to give the country a look at all the candidates on even ground and judge them by their ideas and competency. Rigging the game to reinforce existing prejudices is counterproductive.

The still deeper question relates to the more fundamental idea of the impact of large social systems on group behavior. Social systems operate by both hard and soft rules. The hard rules are laws and regulations. The soft rules are cultural expectations and norms. There is an aggregate effect of hard and soft rules on the long term outcome of such systems. For example, we can look at the system of academic publishing – the hard and soft rules that determine which studies get into the peer-reviewed literature. Even subtle biases in this system (such as favoring studies that will have a large impact factor) influences the direction that science takes or the efficiency by which it operates. We need to worry about such effects that are unintended and suboptimal.

This is the big concern with social media. We now have a few social media giants with tremendous power over our culture and society. They may tweak their algorithms to maximize advertising revenue, but have a host of negative unintended consequences on culture and society. Even worse than an unintended consequence, is an intended consequence by a shadow actor. Someone may figure out how to hack the system to unfairly nudge society in their direction.

The fact is we now live in a large global complex technological civilization. Even slight statistical trends in the aggregate behavior of millions or even billions of people can have dramatic effects. These may be effects that no one wants, and that emerge as a type of epiphenomenon driven by quirks in the system. Clearly, as with this study, we need to monitor these systems and their effects. We can then at least engage in a conversation about what changes might improve the system, and avoid collectively running over a cliff that no one sees.