May 08 2020

Spoofing the Lede in Science Journalism

In journalism “burying the lede” means that the truly newsworthy part of a story is not mentioned until deep in the story, rather than up front where it belongs. I tried to find if there is a term that means the opposite – to take something that is not really part of the story and present it as if it the lede. I could not find it. Perhaps it doesn’t exist (if anyone knows of such a term, let me know). So I made up my own – spoofing the lede.

In journalism “burying the lede” means that the truly newsworthy part of a story is not mentioned until deep in the story, rather than up front where it belongs. I tried to find if there is a term that means the opposite – to take something that is not really part of the story and present it as if it the lede. I could not find it. Perhaps it doesn’t exist (if anyone knows of such a term, let me know). So I made up my own – spoofing the lede.

This is very common is science journalism. It entails taking a study, finding, or discovery and not reporting the actual findings of the study up front, but rather reporting one possible implication of the study. This might be purely speculative, even fanciful. For example, take any study that discovers anything about viruses, and the headline might read, “Scientists find possible cure for the common cold.” The study may have nothing at all to do with the common cold.

This comes from journalists (and often those in the press office whose job it is to “sell” the research of their institution) asking the question – what does this mean? What are the implications of this finding that average people can relate to? That is fine, as far as it goes, but there are often two main problems with implementation. The first is when the possible implication is a real stretch. The connection is super thin, even strained. No, that metamaterial will not lead to a “Harry Potter-like invisibility cloak.”

The second is when that thin possible implication of the research is presented as if it is the actual results of the study. That is the false lede that should be buried – put that toward the end of the article, and put it into proper perspective. This kind of research (for example) helps us understand viral replication, and any such knowledge might lead to potential treatments for viral illness, like the common cold. However, it takes decades for such basic research to lead to direct applications, which cannot be predicted.

I do think this is nothing less than a massive systematic failure of popular science communications – focusing on the sexy speculative implication of research, and burying the actual research.

Here are some recent examples. This headline reads, “Artificial intelligence is energy-hungry — new hardware could curb its appetite.”

You may be surprised to find that the research has nothing to do directly with either artificial intelligence or with the power usage of AI applications. This is what they actually found:

We report experimental realization of tree-like conductance states at room temperature in strongly correlated perovskite nickelates by modulating proton distribution under high speed electric pulses.

Now I get that this does not make a sexy headline, and you probably won’t get many people to read that article without prodding them with something a bit more direct. The thing is, this actually is an interesting tiny development, and is a baby step in the direction of coding AI functions into hardware (possibly). For news reporting the challenge is, the vast majority of science news items are tiny steps. It’s like a single basket in a basketball season – it means something, and is part of the overall game and season, but most individual scores are not that exciting and worth a lot of attention. The occasional exceptional score might be, but not most.

So what does this research actually mean? I am not an expert in this area, so I really don’t know. What is reported is that the ability to store tree-like information in different energy states in what is being described as a quantum material can be exploited for hardware coding of functionality. It also is the type of functionality that can be built into AI. The researchers were able to code the numbers 0-9 using this technique, which they say is a fundamental building block of coding. Sure – but it also seems like a very basic function, and a long way to hardcoded AI.

To be clear, I am not downplaying this one advance. Hopefully it will lead to something useful. I also don’t mind the discussion of why the bigger issue – having AI coded into hardware rather than software – is important. The short version is, AI software is very power hungry, and not sustainable as it becomes increasingly embedded in our technology. Hardware designed to take on some AI functions would use less energy, and is therefore worth developing. This is all interesting, but pretty downstream from the findings of this study.

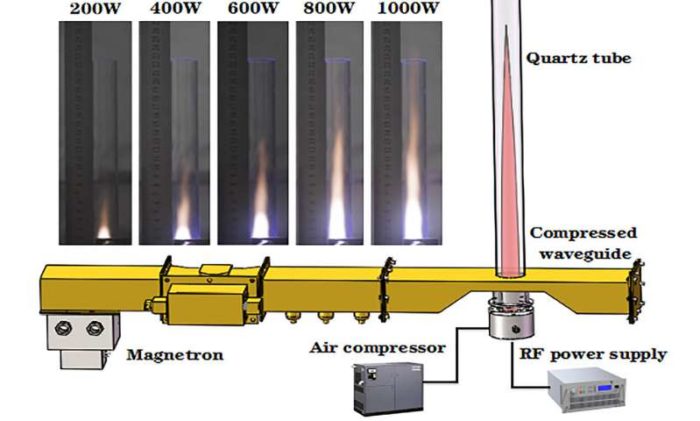

Here is a far worse recently example, in my opinion. The headline read, “Fossil fuel-free jet propulsion with air plasmas.” And to be clear, this is not just about the headline writers. The article itself begins with a discussion of the harms of reliance on fossil fuel. The problem, again, is that this technology development does not really have anything to do with fossil fuel. The development, which is absolutely interesting, is of a device that can create a jet of plasma out of ambient air. If you add enough of these together, you can create thrust equal to current jet engines. Therefore (here is the wild leap) you could theoretically have a jet engine that does not burn fossil fuel, because this engine is powered by electricity.

My problem is that the article nowhere discusses where the energy source of this air plasma engine would come from. This is a non-trivial problem, that probably would keep this approach from ever working ad advertised (fossil fuel-free jet engine). This is partly due to the – all we need to do is scale it up – problem. Scaling up small devices often introduces new problems that may be dealkillers. What is completely unaddressed in this article is, how much energy would such a scaled up engine require? Where would that energy come from? Is it even feasible to have it come from batteries? How large and heavy would all the supporting electronics be? What would the range of a potential aircraft be? Would batteries provide sufficient power output to fly at current commercial speeds, or other applications?

If not batteries, than what would be the power supply? You could have a hydrogen fuel cell. You could, even, burn fossil fuel as your energy source. The article makes it seem like this technology is inherently fossil-fuel free, but it is simply energy source agnostic. And, in fact, it has the same problem that any potential jet aircraft would have – to be practical, you need fuel with a very high energy density to weight. This technology does not solve or even address that problem, beyond being somewhat neutral to energy source. One big advantage to fossil fuels is that they are relatively energy dense compared to other energy sources, especially jet fuel. That’s why “jet fuel” is shorthand for a really powerful energy source.

As the article mentions, plasma thrusters are already in use in space probes, but existing technology cannot be used in an atmosphere. The breakthrough here is designing a plasma thruster that uses air and is usable within an atmosphere, so sure, this theoretically creates the potential to have air-plasma jet propulsion. It may have other applications as well, perhaps is launching rockets before they leave the atmosphere, for example. We will see. But the jet application has serious hurdles, not addressed by this technology, and therefore leaping to that specific application, and specifically without the use of fossil fuels for energy, is an unsupported leap. The reporting, in my opinion, essentially misleads the public about the nature of this development.

Sure, if you read carefully throughout the entire article and ask yourself all the right questions, much of the information is there. But that is a really low bar for good science journalism. Ideally a lay person should read the headline and have a decent idea of what is going on. And someone who reads the first 1-2 paragraphs should have the basic story. But often reading only the leading paragraphs would give a complete misconception about the science news. We can do better.