Dec

23

2024

The latest flap over drone sightings in New Jersey and other states in the North East appears to be – essentially nothing. Or rather, it’s a classic example of a mass panic. There are reports of “unusual” drone activity, which prompts people to look for drones, which results in people seeing drones or drone-like objects and therefore reporting them, leading to more drone sightings. Lather, rinse, repeat. The news media happily gets involved to maximize the sensationalism of the non-event. Federal agencies eventually comment in a “nothing to see here” style that just fosters more speculation. UFO and other fringe groups confidently conclude that whatever is happening is just more evidence for whatever they already believed in.

The latest flap over drone sightings in New Jersey and other states in the North East appears to be – essentially nothing. Or rather, it’s a classic example of a mass panic. There are reports of “unusual” drone activity, which prompts people to look for drones, which results in people seeing drones or drone-like objects and therefore reporting them, leading to more drone sightings. Lather, rinse, repeat. The news media happily gets involved to maximize the sensationalism of the non-event. Federal agencies eventually comment in a “nothing to see here” style that just fosters more speculation. UFO and other fringe groups confidently conclude that whatever is happening is just more evidence for whatever they already believed in.

I am not exempting myself from the cycle either. Skeptics are now part of the process, eventually explaining how the whole thing is a classic example of some phenomenon of human self-deception, failure of critical thinking skills, and just another sign of our dysfunctional media ecosystem. But I do think this is a healthy part of the media cycle. One of the roles that career skeptics play is to be the institutional memory for weird stuff like this. We can put such events rapidly into perspective because we have studied the history and likely been through numerous such events before.

Before I get to that bigger picture, here is a quick recap. In November there were sightings in New Jersey of “mysterious” drone activity. I don’t know exactly what made them mysterious, but it lead to numerous reportings of other drone sightings. Some of those sightings were close to a military base, Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst, and some were concerned of a security threat. Even without the UFO/UAP angle, there is concern about foreign powers using drones for spying or potentially as a military threat. This is perhaps enhanced by all the reporting of the major role that drones are playing in the Russian-Ukraine war. Some towns in Southern New Jersey have banned the use of drones temporarily, and the FAA has also restricted some use.

A month after the first sightings Federal officials have stated that the sightings that have been investigated have all turned out to be drones, planes mistaken for drones, and even stars mistaken for drones. None have turned out to be anything mysterious or nefarious. So the drones, it turns out, are mostly drones.

Continue Reading »

Dec

13

2024

A recent BBC article highlights some of the risk of the new age of social media we have crafted for ourselves. The BBC investigated the number one ranked UK podcast, Diary of a CEO with host Steven Bartlett, for the accuracy of the medical claims recently made on the show. While the podcast started out as focusing on tips from successful businesspeople, it has recently turned toward unconventional medical opinions as this has boosted downloads.

A recent BBC article highlights some of the risk of the new age of social media we have crafted for ourselves. The BBC investigated the number one ranked UK podcast, Diary of a CEO with host Steven Bartlett, for the accuracy of the medical claims recently made on the show. While the podcast started out as focusing on tips from successful businesspeople, it has recently turned toward unconventional medical opinions as this has boosted downloads.

“In an analysis of 15 health-related podcast episodes, BBC World Service found each contained an average of 14 harmful health claims that went against extensive scientific evidence.”

These includes showcasing an anti-vaccine crank, Dr. Malhotra, who claimed that the “Covid vaccine was a net negative for society”. Meanwhile the WHO estimates that the COVID vaccine saved 14 million lives worldwide. A Lancet study estimates that in the European region alone the vaccine saved 1.4 million lives. This number could have been greater were in not for the very type of antivaccine misinformation spread by Dr. Malhotra.

Another guest promoted the Keto diet as a treatment for cancer. Not only is there no evidence to support this claim, dietary restrictions while undergoing treatment for cancer can be very dangerous, and imperil the health of cancer patients.

This reminds me of the 2014 study that found that, “For recommendations in The Dr Oz Show, evidence supported 46%, contradicted 15%, and was not found for 39%.” Of course, evidence published in the BMJ does little to counter misinformation spread on extremely popular shows. The BBC article highlights the fact that in the UK podcasts are not covered by the media regulator Ofcom, which has standards of accuracy and fairness for legacy media.

Continue Reading »

Dec

12

2024

Why does news reporting of science and technology have to be so terrible at baseline? I know the answers to this question – lack of expertise, lack of a business model to support dedicated science news infrastructure, the desire for click-bait and sensationalism – but it is still frustrating that this is the case. Social media outlets do allow actual scientists and informed science journalists to set the record straight, but they are also competing with millions of pseudoscientific, ideological, and other outlets far worse than mainstream media. In any case, I’m going to complain about while I try to do my bit to set the record straight.

Why does news reporting of science and technology have to be so terrible at baseline? I know the answers to this question – lack of expertise, lack of a business model to support dedicated science news infrastructure, the desire for click-bait and sensationalism – but it is still frustrating that this is the case. Social media outlets do allow actual scientists and informed science journalists to set the record straight, but they are also competing with millions of pseudoscientific, ideological, and other outlets far worse than mainstream media. In any case, I’m going to complain about while I try to do my bit to set the record straight.

I wrote about nuclear diamond batteries in 2020. The concept is intriguing but the applications very limited, and cost likely prohibitive for most uses. The idea is that you take a bit of radioactive material and surround it with “diamond like carbon” which serves two purposes. It prevents leaking of radiation to the environment, and it capture the beta decay and converts it into a small amount of electricity. This is not really a battery (a storage of energy) but an energy cell that produces energy, but it would have some battery-like applications.

The first battery based on this concept, capturing the beta decay of a radioactive substance to generate electricity, was in 1913, made by physicist Henty Moseley. So year, despite the headlines about the “first of its kind” whatever, we have had nuclear batteries for over a hundred years. The concept of using diamond like carbon goes back to 2016, with the first prototype created in 2018.

So of course I was disappointed when the recent news reporting on another such prototype declares this is a “world first” without putting it into any context. It is reporting on a new prototype that does have a new feature, but they make it sound like this is the first nuclear battery, when it’s not even the first diamond nuclear battery. The new prototype is a diamond nuclear battery using Carbon-14 and the beta decay source. They make diamond like carbon out of C-14 and surround it with diamond like carbon made from non-radioactive carbon. C-14 has a half life of 5,700 years, so they claim the battery lasts of over 5,000 years.

Continue Reading »

Jul

09

2024

In an optimally rational person, what should govern their perception of risk? Of course, people are generally not “optimally rational”. It’s therefore an interesting thought experiment – what would be optimal, and how does that differ from how people actually assess risk? Risk is partly a matter of probability, and therefore largely comes down to simple math – what percentage of people who engage in X suffer negative consequence Y? To accurately assess risk, you therefore need information. But that is not how people generally operate.

In an optimally rational person, what should govern their perception of risk? Of course, people are generally not “optimally rational”. It’s therefore an interesting thought experiment – what would be optimal, and how does that differ from how people actually assess risk? Risk is partly a matter of probability, and therefore largely comes down to simple math – what percentage of people who engage in X suffer negative consequence Y? To accurately assess risk, you therefore need information. But that is not how people generally operate.

In a recent study assessment of the risk of autonomous vehicles was evaluated in 323 US adults. This is a small study, and all the usual caveats apply in terms of how questions were asked. But if we take the results at face value, they are interesting but not surprising. First, information itself did not have a significant impact on risk perception. What did have a significant impact was trust, or more specifically, trust had a significant impact on the knowledge and risk perception relationship.

What I think this means is that knowledge alone does not influence risk perception, unless it was also coupled with trust. This actually makes sense, and is rational. You have to trust the information you are getting in order to confidently use it to modify your perception of risk. However – trust is a squirrely thing. People tend not to trust things that are new and unfamiliar. I would consider this semi-rational. It is reasonable to be cautious about something that is unfamiliar, but this can quickly turn into a negative bias that is not rational. This, of course, goes beyond autonomous vehicles to many new technologies, like GMOs and AI.

Continue Reading »

May

13

2024

There is an interesting disconnect in our culture recently. About 90% of people claim that they verify information they encounter in the news and on social media, and 96% of Americans say that we need to limit the spread of misinformation online. And yet, the spread of misinformation is rampant. Most people, 74%, report that that they have seen information online labeled as false. Only about 60% of people report regularly checking information before sharing it. And a relatively small number of users spread a disproportionate amount of misinformation.

Of course, what is considered “misinformation” is often is the eyes of the beholder. We tend to silo ourselves in information ecosystems that share our worldview, and define misinformation relative to our chosen outlets. Republicans and Democrats, for example, trust completely different sources of news, with no overlap (in the most trusted sources). What’s fake news on Fox, is mainstream news on MSNBC, and vice versa. There is not only a difference in what is considered real vs fake news, but how the news is curated. Choosing certain stories to amplify over others can greatly distort one’s view of reality.

Misinformation is not new, but the networks of how it is created and shared is changing fairly quickly. If we all agree we need to stem the tide of misinformation, how do we do it? As is often the case with big social or systemic questions like this, we can take a top-down or bottom-up approach. The top-down approach is for social media platforms and news outlets to take responsibility for the quality of the information being spread on their watch. Clear misinformation can be identified and then nipped in the bud. AI algorithms backed up by human evaluators can kill a lot of misinformation, if the platform wants. Also, they can choose algorithms that favor quality and reliability over sensationalism and maximizing clicks and eyeballs. In addition, government regulations can influence the incentives for platforms and outlets to favor reliability over sensationalism.

Continue Reading »

Nov

16

2023

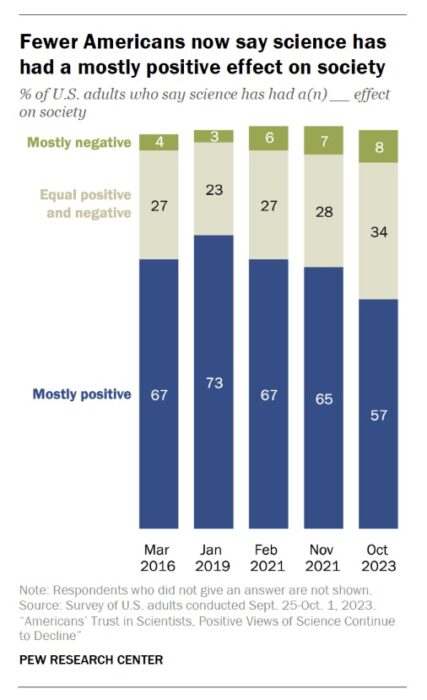

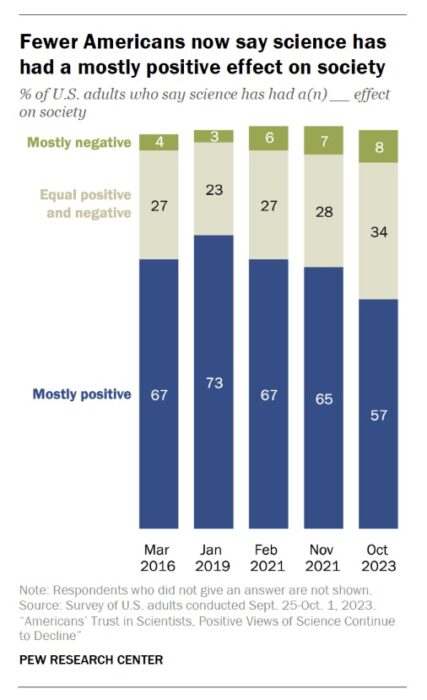

How much does the public trust in science and scientists? Well, there’s some good news and some bad news. Let’s start with the bad news – a recent Pew survey finds that trust in scientist has been in decline for the last few years. From its recent peak in 2019, those who answered that science has a mostly positive effect on society decreased from 73% to 57%. Those who say it has a mostly negative effect increased from 3 to 8%. Those who trust in scientists a fair amount or a great deal decreased from 86 to 73%. Those who think that scientific investments are worthwhile remain strong at 78%.

How much does the public trust in science and scientists? Well, there’s some good news and some bad news. Let’s start with the bad news – a recent Pew survey finds that trust in scientist has been in decline for the last few years. From its recent peak in 2019, those who answered that science has a mostly positive effect on society decreased from 73% to 57%. Those who say it has a mostly negative effect increased from 3 to 8%. Those who trust in scientists a fair amount or a great deal decreased from 86 to 73%. Those who think that scientific investments are worthwhile remain strong at 78%.

The good news is that these numbers are relatively high compared to other institutions and professions. Science and scientists still remain among the most respected professions, behind the military, teachers, and medical doctors, and way above journalists, clergy, business executives, and lawyers. So overall a majority of Americans feel that science and scientists are trustworthy, valuable, and a worthwhile investment.

But we need to pay attention to early warning signs that this respect may be in jeopardy. If we get to the point that a majority of the public do not feel that investment in research is worthwhile, or that the findings of science can be trusted, that is a recipe for disaster. In the modern world, such a society is likely not sustainable, certainly not as a stable democracy and economic leader. It’s worthwhile, therefore, to dig deeper on what might be behind the recent dip in numbers.

It’s worth pointing out some caveats. Surveys are always tricky, and the results depend heavily on how questions are asked. For example, if you ask people if they trust “doctors” in the abstract the number is typically lower than if you ask them if they trust their doctor. People tend to separate their personal experience from what they think is going on generally in society, and are perhaps too willing to dismiss their own evidence as “exceptions”. If they were favoring data over personal anecdote, that would be fine. But they are often favoring rumor, fearmongering, and sensationalism. Surveys like this, therefore, often reflect the public mood, rather than deeply held beliefs.

Continue Reading »

Jan

26

2023

Grand conspiracy theories are a curious thing. What would lead someone to readily believe that the world is secretly run by evil supervillains? Belief in conspiracies correlates with feelings of helplessness, which suggests that some people would rather believe that an evil villain is secretly in control than the more prosaic reality that no one is in control and we live in a complex and chaotic universe.

Grand conspiracy theories are a curious thing. What would lead someone to readily believe that the world is secretly run by evil supervillains? Belief in conspiracies correlates with feelings of helplessness, which suggests that some people would rather believe that an evil villain is secretly in control than the more prosaic reality that no one is in control and we live in a complex and chaotic universe.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided a natural experiment to see how conspiracy belief reacted and spread. A recent study examines this phenomenon by tracking tweets and other social media posts relating to COVID conspiracy theories. Their primary method was to identify specific content type within the tweets and correlate that with how quickly and how far those tweets were shared across the network.

The researchers identified nine features of COVID-related conspiracy tweets: malicious purposes, secretive action, statement of belief, attempt at authentication (such as linking to a source), directive (asking the reader to take action), rhetorical question, who are the conspirators, methods of secrecy, and conditions under which the conspiracy theory is proposed (I got COVID from that 5G tower near my home). They also propose a breakdown of different types of conspiracies: conspiracy sub-narrative, issue specific, villain-based, and mega-conspiracy.

Continue Reading »

Feb

07

2022

The latest controversy over Joe Rogan and Spotify is a symptom of a long-standing trend, exacerbated by social media but not caused by it. The problem is with the algorithms used by media outlets to determine what to include on their platform.

The latest controversy over Joe Rogan and Spotify is a symptom of a long-standing trend, exacerbated by social media but not caused by it. The problem is with the algorithms used by media outlets to determine what to include on their platform.

The quick summary is that Joe Rogan’s podcast is the most popular podcast in the world with millions of listeners. Rogan follows a long interview format, and he is sometimes criticized for having on guests that promote pseudoscience or misinformation, for not holding them to account, or for promoting misinformation himself. In particular he has come under fire for spreading dangerous COVID misinformation during a health crisis, specifically his interview with Dr. Malone. In an open letter to Rogan’s podcast host, Spotify, health experts wrote:

“With an estimated 11 million listeners per episode, JRE, which is hosted exclusively on Spotify, is the world’s largest podcast and has tremendous influence,” the letter reads. “Spotify has a responsibility to mitigate the spread of misinformation on its platform, though the company presently has no misinformation policy.”

Then Neil Young gave Spotify an ultimatum – either Rogan goes, or he goes. Spotify did not respond, leading to Young pulling his entire catalog of music from the platform. Other artists have also joined the boycott. This entire episode has prompted yet another round of discussion over censorship and the responsibility of media platforms, outlets, and content producers. Rogan himself produced a video to explain his position. The video is definitively not an apology or even an attempt at one. In it Rogan makes two core points. The first is that he himself is not an expert of any kind, therefore he should not be held responsible for the scientific accuracy of what he says or the questions he asks. Second, his goal with the podcast is to simply interview interesting people. Rogan has long used these two points to absolve himself of any journalistic responsibility, so this is nothing new. He did muddy the waters a little when he went on to say that maybe he can research his interviewees more thoroughly to ask better informed questions, but this was presented as more of an afterthought. He stands by his core justifications.

Continue Reading »

Aug

18

2020

This is one of those things that futurists did not predict at all, but now seems obvious and unavoidable – the degree to which computer algorithms affect your life. It’s always hard to make negative statements, and they have to be qualified – but I am not aware of any pre-2000 science fiction or futurism that even discussed the role of social media algorithms or other informational algorithms on society and culture (as always, let me know if I’m missing something). But in a very short period of time they have become a major challenge for many societies. It also is now easy to imagine how computer algorithms will be a dominant topic in the future. People will likely debate their role, who controls them and who should control them, and what regulations, if any, should be put in place.

This is one of those things that futurists did not predict at all, but now seems obvious and unavoidable – the degree to which computer algorithms affect your life. It’s always hard to make negative statements, and they have to be qualified – but I am not aware of any pre-2000 science fiction or futurism that even discussed the role of social media algorithms or other informational algorithms on society and culture (as always, let me know if I’m missing something). But in a very short period of time they have become a major challenge for many societies. It also is now easy to imagine how computer algorithms will be a dominant topic in the future. People will likely debate their role, who controls them and who should control them, and what regulations, if any, should be put in place.

The worse outcome is if this doesn’t happen, meaning that people are not aware of the role of algorithms in their life and who controls them. That is essentially what is happening in China and other authoritarian nations. Social media algorithms are an authoritarian’s dream – they give them incredible power to control what people see, what information they get exposed to, and to some extent what they think. This is 1984 on steroids. Orwell imagined that in order to control what and how people think authoritarians would control language (double-plus good). Constrain language and you constrain thought. That was an interesting idea pre-web and pre-social media. Now computer algorithms can control the flow of information, and by extension what people know and think, seamlessly, invisibly, and powerfully to a scary degree.

Even in open democratic societies, however, the invisible hand of computer algorithms can wreak havoc. Social scientists studying this phenomenon are increasing sounding warning bells. A recent example is an anti-extremist group in the UK who now are warning, according to their research, that Facebook algorithms are actively promoting holocaust denial and other conspiracy theories. They found, unsurprisingly, that visitors to Facebook pages that deny the holocaust were then referred to other pages that also deny the holocaust. This in turn leads to other conspiracies that also refer to still other conspiracy content, and down the rabbit hole you go.

Continue Reading »

Sep

23

2019

One experience I have had many times is with colleagues or friends who are not aware of the problem of pseudoscience in medicine. At first they are in relative denial – “it can’t be that bad.” “Homeopathy cannot possibly be that dumb!” Once I have had an opportunity to explain it to them sufficiently and they see the evidence for themselves, they go from denial to outrage. They seem to go from one extreme to the other, thinking pseudoscience is hopelessly rampant, and even feeling nihilistic.

One experience I have had many times is with colleagues or friends who are not aware of the problem of pseudoscience in medicine. At first they are in relative denial – “it can’t be that bad.” “Homeopathy cannot possibly be that dumb!” Once I have had an opportunity to explain it to them sufficiently and they see the evidence for themselves, they go from denial to outrage. They seem to go from one extreme to the other, thinking pseudoscience is hopelessly rampant, and even feeling nihilistic.

This general phenomenon is not limited to medical pseudoscience, and I think it applies broadly. We may be unaware of a problem, but once we learn to recognize it we see it everywhere. Confirmation bias kicks in, and we initially overapply the lessons we recently learned.

I have this problem when I give skeptical lectures. I can spend an hour discussing publication bias, researcher bias, p-hacking, the statistics about error in scientific publications, and all the problems with scientific journals. At first I was a little surprised at the questions I would get, expressing overall nihilism toward science in general. I inadvertently gave the wrong impression by failing to properly balance the lecture. These are all challenges to good science, but good science can and does get done. It’s just harder than many people think.

This relates to Aristotle’s philosophy of the mean – virtue is often a balance between two extreme vices. Similarly, I find there is often a nuanced position on many topics balanced precariously between two extremes. We can neither trust science and scientists explicitly, nor should we dismiss all of science as hopelessly biased and flawed. Freedom of speech is critical for democracy, but that does not mean freedom from the consequences of your speech, or that everyone has a right to any venue they choose.

A recent Guardian article about our current post-truth world reminded me of this philosophy of the mean. To a certain extent, society has gone from one extreme to the other when it comes to facts, expertise, and trusting authoritative sources. This is a massive oversimplification, and of course there have always been people everywhere along this spectrum. But there does seem to have been a shift. In the pre-social media age most people obtained their news from mainstream sources that were curated and edited. Talking head experts were basically trusted, and at least the broad center had a source of shared facts from which to debate.

Continue Reading »

The latest flap over drone sightings in New Jersey and other states in the North East appears to be – essentially nothing. Or rather, it’s a classic example of a mass panic. There are reports of “unusual” drone activity, which prompts people to look for drones, which results in people seeing drones or drone-like objects and therefore reporting them, leading to more drone sightings. Lather, rinse, repeat. The news media happily gets involved to maximize the sensationalism of the non-event. Federal agencies eventually comment in a “nothing to see here” style that just fosters more speculation. UFO and other fringe groups confidently conclude that whatever is happening is just more evidence for whatever they already believed in.

The latest flap over drone sightings in New Jersey and other states in the North East appears to be – essentially nothing. Or rather, it’s a classic example of a mass panic. There are reports of “unusual” drone activity, which prompts people to look for drones, which results in people seeing drones or drone-like objects and therefore reporting them, leading to more drone sightings. Lather, rinse, repeat. The news media happily gets involved to maximize the sensationalism of the non-event. Federal agencies eventually comment in a “nothing to see here” style that just fosters more speculation. UFO and other fringe groups confidently conclude that whatever is happening is just more evidence for whatever they already believed in.

A

A  Why does news reporting of science and technology have to be so terrible at baseline? I know the answers to this question – lack of expertise, lack of a business model to support dedicated science news infrastructure, the desire for click-bait and sensationalism – but it is still frustrating that this is the case. Social media outlets do allow actual scientists and informed science journalists to set the record straight, but they are also competing with millions of pseudoscientific, ideological, and other outlets far worse than mainstream media. In any case, I’m going to complain about while I try to do my bit to set the record straight.

Why does news reporting of science and technology have to be so terrible at baseline? I know the answers to this question – lack of expertise, lack of a business model to support dedicated science news infrastructure, the desire for click-bait and sensationalism – but it is still frustrating that this is the case. Social media outlets do allow actual scientists and informed science journalists to set the record straight, but they are also competing with millions of pseudoscientific, ideological, and other outlets far worse than mainstream media. In any case, I’m going to complain about while I try to do my bit to set the record straight. In an optimally rational person, what should govern their perception of risk? Of course, people are generally not “optimally rational”. It’s therefore an interesting thought experiment – what would be optimal, and how does that differ from how people actually assess risk? Risk is partly a matter of probability, and therefore largely comes down to simple math – what percentage of people who engage in X suffer negative consequence Y? To accurately assess risk, you therefore need information. But that is not how people generally operate.

In an optimally rational person, what should govern their perception of risk? Of course, people are generally not “optimally rational”. It’s therefore an interesting thought experiment – what would be optimal, and how does that differ from how people actually assess risk? Risk is partly a matter of probability, and therefore largely comes down to simple math – what percentage of people who engage in X suffer negative consequence Y? To accurately assess risk, you therefore need information. But that is not how people generally operate. How much does the public trust in science and scientists? Well, there’s some good news and some bad news. Let’s start with the bad news –

How much does the public trust in science and scientists? Well, there’s some good news and some bad news. Let’s start with the bad news – Grand conspiracy theories are a curious thing. What would lead someone to readily believe that the world is secretly run by evil supervillains? Belief in conspiracies correlates with feelings of helplessness, which suggests that some people would rather believe that an evil villain is secretly in control than the more prosaic reality that no one is in control and we live in a complex and chaotic universe.

Grand conspiracy theories are a curious thing. What would lead someone to readily believe that the world is secretly run by evil supervillains? Belief in conspiracies correlates with feelings of helplessness, which suggests that some people would rather believe that an evil villain is secretly in control than the more prosaic reality that no one is in control and we live in a complex and chaotic universe. The latest controversy over Joe Rogan and Spotify is a symptom of a long-standing trend, exacerbated by social media but not caused by it. The problem is with the algorithms used by media outlets to determine what to include on their platform.

The latest controversy over Joe Rogan and Spotify is a symptom of a long-standing trend, exacerbated by social media but not caused by it. The problem is with the algorithms used by media outlets to determine what to include on their platform. This is one of those things that futurists did not predict at all, but now seems obvious and unavoidable – the degree to which computer algorithms affect your life. It’s always hard to make negative statements, and they have to be qualified – but I am not aware of any pre-2000 science fiction or futurism that even discussed the role of social media algorithms or other informational algorithms on society and culture (as always, let me know if I’m missing something). But in a very short period of time they have become a major challenge for many societies. It also is now easy to imagine how computer algorithms will be a dominant topic in the future. People will likely debate their role, who controls them and who should control them, and what regulations, if any, should be put in place.

This is one of those things that futurists did not predict at all, but now seems obvious and unavoidable – the degree to which computer algorithms affect your life. It’s always hard to make negative statements, and they have to be qualified – but I am not aware of any pre-2000 science fiction or futurism that even discussed the role of social media algorithms or other informational algorithms on society and culture (as always, let me know if I’m missing something). But in a very short period of time they have become a major challenge for many societies. It also is now easy to imagine how computer algorithms will be a dominant topic in the future. People will likely debate their role, who controls them and who should control them, and what regulations, if any, should be put in place. One experience I have had many times is with colleagues or friends who are not aware of the problem of pseudoscience in medicine. At first they are in relative denial – “it can’t be that bad.” “Homeopathy cannot possibly be that dumb!” Once I have had an opportunity to explain it to them sufficiently and they see the evidence for themselves, they go from denial to outrage. They seem to go from one extreme to the other, thinking pseudoscience is hopelessly rampant, and even feeling nihilistic.

One experience I have had many times is with colleagues or friends who are not aware of the problem of pseudoscience in medicine. At first they are in relative denial – “it can’t be that bad.” “Homeopathy cannot possibly be that dumb!” Once I have had an opportunity to explain it to them sufficiently and they see the evidence for themselves, they go from denial to outrage. They seem to go from one extreme to the other, thinking pseudoscience is hopelessly rampant, and even feeling nihilistic.