Oct 23 2023

Panspermia Again

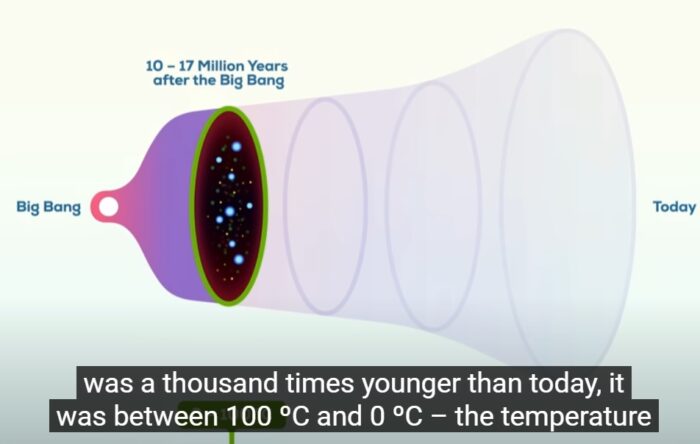

Recently I was asked what I thought about this video, which suggests it is possible that life formed in the early universe, shortly after the Big Bang. Although no mentioned specifically in the video, the ideas presents are essentially panspermia – the idea that life formed in the early universe and then spread as “seeds” throughout the universe, taking root in suitable environments like the early Earth. While the narrator admits these ideas are “speculative”, he presents what I feel is an extremely biased favorable take on the ideas being presented.

Recently I was asked what I thought about this video, which suggests it is possible that life formed in the early universe, shortly after the Big Bang. Although no mentioned specifically in the video, the ideas presents are essentially panspermia – the idea that life formed in the early universe and then spread as “seeds” throughout the universe, taking root in suitable environments like the early Earth. While the narrator admits these ideas are “speculative”, he presents what I feel is an extremely biased favorable take on the ideas being presented.

The video starts by arguing that life on Earth arose very quickly, perhaps implausibly quickly. The Earth is 4.5 billion years old, and it likely cooled sufficiently to be compatible with life around 4.3 billion years ago. The oldest fossils are 3.7 billion years old, which leaves a 600 million year window in which life could have developed from prebiotic molecules. When during that time did these complex molecules cross the line to be considered life is unknown, but it seems like there was probably 1-2 hundred million years for this to happen. The video argues that this was simply not enough time – so perhaps life already existed and seeded the Earth. But this argument is not valid. We do not have any information that would indicate something on the order of 100 million years was not enough time for the simplest type of life to form. So they set up a fake problem in order to introduce their unnecessary “solution”.

But the argument gets worse from there. Most of the video is spent speculating about the fact that between 10 million and 17 million years ago the temperature of the universe would have been between 100 C and 0 C, the temperature range of liquid water. During this time, life could have formed everywhere in the universe. But there is a glaring problem with this argument, that the video hand-waves away with a giant “may”.

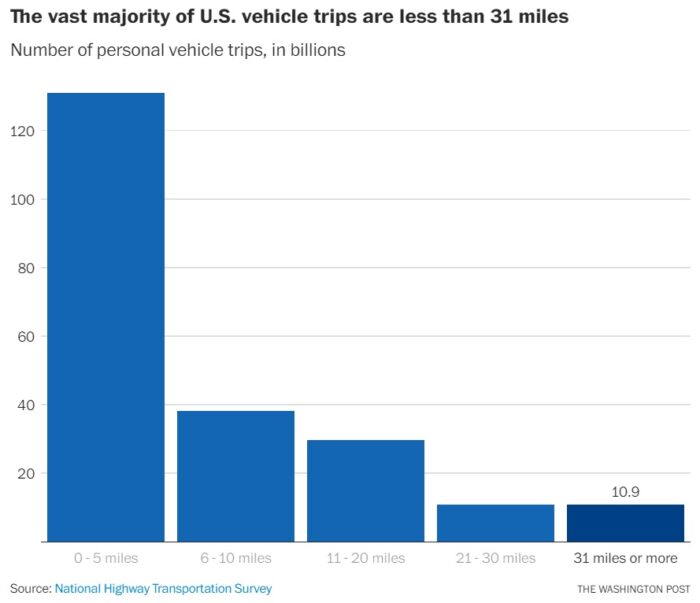

One of the key components of the plan to get our civilization to net zero by 2050 is to transform the motor vehicle fleet into all electric vehicles (EVs). This is a worthy goal, as it would eliminate burning gasoline for transportation. In fact it’s necessary if we want to get near net zero. Governments and the auto industry are responding with incentives for EVs, some regulations forcing the phasing out of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, and investment of billions even trillions of dollars to change over production lines, secure raw material sources, and build charging stations.

One of the key components of the plan to get our civilization to net zero by 2050 is to transform the motor vehicle fleet into all electric vehicles (EVs). This is a worthy goal, as it would eliminate burning gasoline for transportation. In fact it’s necessary if we want to get near net zero. Governments and the auto industry are responding with incentives for EVs, some regulations forcing the phasing out of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, and investment of billions even trillions of dollars to change over production lines, secure raw material sources, and build charging stations. Psychologists have been studying a very basic cognitive function that appears to be of increasing importance – how do we choose what to believe as true or false? We live in a world awash in information, and access to essentially the world’s store of knowledge is now a trivial matter for many people, especially in developed parts of the world. The most important cognitive skill in the 21st century may arguably be not factual knowledge but truth discrimination. I would argue this is a skill that needs to be explicitly taught in school, and is more important than teaching students facts.

Psychologists have been studying a very basic cognitive function that appears to be of increasing importance – how do we choose what to believe as true or false? We live in a world awash in information, and access to essentially the world’s store of knowledge is now a trivial matter for many people, especially in developed parts of the world. The most important cognitive skill in the 21st century may arguably be not factual knowledge but truth discrimination. I would argue this is a skill that needs to be explicitly taught in school, and is more important than teaching students facts. The climate change discussion would benefit most from good-faith evidence and science-based discussion. Unfortunately, humans tend to prefer emotion, ideology, motivated reasoning, and confirmation bias. As an example, I was sent an excerpt from a climate change podcast as a “rebuttal” to my position. The content, however, does not address my actual position, and I find many of the arguments highly problematic. This one is coming from a perspective that climate change is real and a definite problem that needs to be addressed, but seems to be advocating that the best solution is to be all-in on wind and solar without needing other solutions.

The climate change discussion would benefit most from good-faith evidence and science-based discussion. Unfortunately, humans tend to prefer emotion, ideology, motivated reasoning, and confirmation bias. As an example, I was sent an excerpt from a climate change podcast as a “rebuttal” to my position. The content, however, does not address my actual position, and I find many of the arguments highly problematic. This one is coming from a perspective that climate change is real and a definite problem that needs to be addressed, but seems to be advocating that the best solution is to be all-in on wind and solar without needing other solutions. On the current episode of the SGU, because it is pride month, we expressed our general support for the LGBTQ community. I also opined about how important it is to respect individual liberty, the freedom to simply live your authentic life as you choose, and how ironic it is that often the people screaming the loudest about liberty seem the most willing to take it away from others. That was it – we didn’t get into any specific issues. And yet this discussion provoked several responses, filled with strawman accusations about things we never said, and weighed down with a typical list of tropes and canards. It would take many articles to address them all, so I will focus on just one here. One e-mailer claimed: “It is obvious to me that the 98% of trans people have a mental illness that should be treated like any other mental illnesses.”

On the current episode of the SGU, because it is pride month, we expressed our general support for the LGBTQ community. I also opined about how important it is to respect individual liberty, the freedom to simply live your authentic life as you choose, and how ironic it is that often the people screaming the loudest about liberty seem the most willing to take it away from others. That was it – we didn’t get into any specific issues. And yet this discussion provoked several responses, filled with strawman accusations about things we never said, and weighed down with a typical list of tropes and canards. It would take many articles to address them all, so I will focus on just one here. One e-mailer claimed: “It is obvious to me that the 98% of trans people have a mental illness that should be treated like any other mental illnesses.” I have been writing blog posts and engaging in science communication long enough that I have a pretty good sense how much engagement I am going to get from a particular topic. Some topics are simply more divisive than others (although there is an unpredictable element from social media networks). I wish I could say that the more scientifically interesting topics garnered more attention and comments, but that is not the case. The overall pattern is that topics which have an ideological angle or affect people’s world-view inspire more passionate criticism or defense. Timed drug release is an important topic, with implications for potentially anyone who has to take medication at some point in their lives. But it doesn’t challenge anyone’s world view. ESP, on the other hand, is a fringe topic likely to directly affect no one, but apparently is 70 times more interesting to my readers (using comments as a measure).

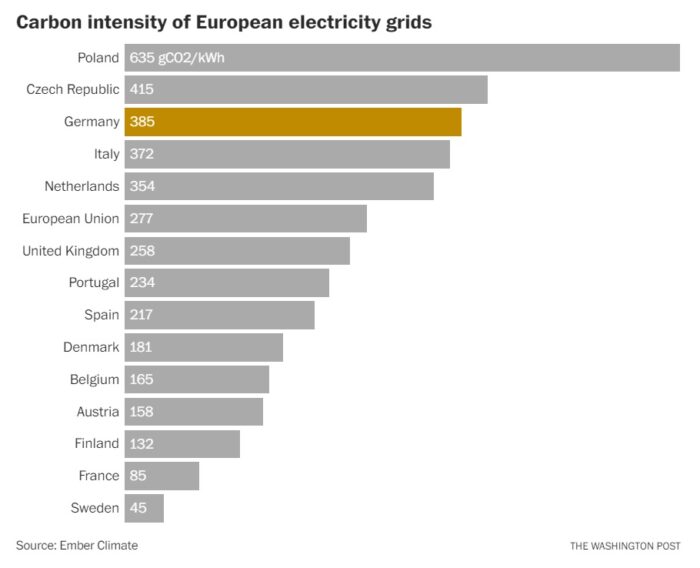

I have been writing blog posts and engaging in science communication long enough that I have a pretty good sense how much engagement I am going to get from a particular topic. Some topics are simply more divisive than others (although there is an unpredictable element from social media networks). I wish I could say that the more scientifically interesting topics garnered more attention and comments, but that is not the case. The overall pattern is that topics which have an ideological angle or affect people’s world-view inspire more passionate criticism or defense. Timed drug release is an important topic, with implications for potentially anyone who has to take medication at some point in their lives. But it doesn’t challenge anyone’s world view. ESP, on the other hand, is a fringe topic likely to directly affect no one, but apparently is 70 times more interesting to my readers (using comments as a measure). Germany has been thrown around a lot as an example of both what to do and what not to do in terms of addressing global warming by embracing green energy technology. It’s possible to look back now and review the numbers, to see what the effect was of its decision to embrace renewable technology and actively shut down their nuclear power plants. The numbers, I think, tell a pretty clear story.

Germany has been thrown around a lot as an example of both what to do and what not to do in terms of addressing global warming by embracing green energy technology. It’s possible to look back now and review the numbers, to see what the effect was of its decision to embrace renewable technology and actively shut down their nuclear power plants. The numbers, I think, tell a pretty clear story.