Feb 09 2021

Nudging Behavior

Like it or not, we live in a society of other people, and we share resources, the environment, and infrastructure. This means that how other people behave and the choices they make affect you, as your choices affect others. Even if you live alone in the woods, your behavior affects the local environment, even if in a small way. As a result there are multiple layers of complex rules governing how we interact with each other in countless contexts. We have evolved a layer of rules, involving guilt, shame, a sense of justice, and other emotions, that powerfully govern our behavior. We have developed explicit laws and regulations that enforce rules by authority and power. And every culture and subculture tends to develop norms of behavior or “soft” rules that are enforced through peer pressure.

Like it or not, we live in a society of other people, and we share resources, the environment, and infrastructure. This means that how other people behave and the choices they make affect you, as your choices affect others. Even if you live alone in the woods, your behavior affects the local environment, even if in a small way. As a result there are multiple layers of complex rules governing how we interact with each other in countless contexts. We have evolved a layer of rules, involving guilt, shame, a sense of justice, and other emotions, that powerfully govern our behavior. We have developed explicit laws and regulations that enforce rules by authority and power. And every culture and subculture tends to develop norms of behavior or “soft” rules that are enforced through peer pressure.

The question is – how do we optimize these rules at every level in order to make our world as good as possible for as many people as possible? This includes balancing many concerns, including individual liberty, that are often at cross-purposes. And of course, different cultures will find a different optimal balance.

Implicit in this question is a more fundamental question – how do we affect people’s behavior? Whether or not we should has already been answered – yes, we should. The alternative in anarchy. Even if you are an extreme libertarian, you still want to influence other people’s behavior, just through market forces rather than laws. And I think even the most extreme libertarian would agree that things like murder should be illegal. Back to the real question, how do we affect behavior? Doing so by fiat definitely works – if you arrest someone and throw them in jail, you are taking direct physical control of their behavior. It seems obvious that such extreme measures should be a last resort, not a primary method of behavior modification.

At the other end of the spectrum is what is called a nudge. A recent study defines nudges this way:

Nudges are low-cost interventions that influence decision-making without limiting freedom of choice and have been tested in the environmental realm of electricity and water saving, reduced meat consumption, recycling, and decreasing private car transportation (Kollmuss and Agyeman, 2002; Cheng et al., 2011; Osbaldiston and Schott, 2012). Sunstein (2014) notes that nudging refers to “liberty-preserving approaches that steer people in particular directions, but that also allow them to go their own way” (p. 583), and that nudges “are specifically designed to preserve full freedom of choice” (p. 584).

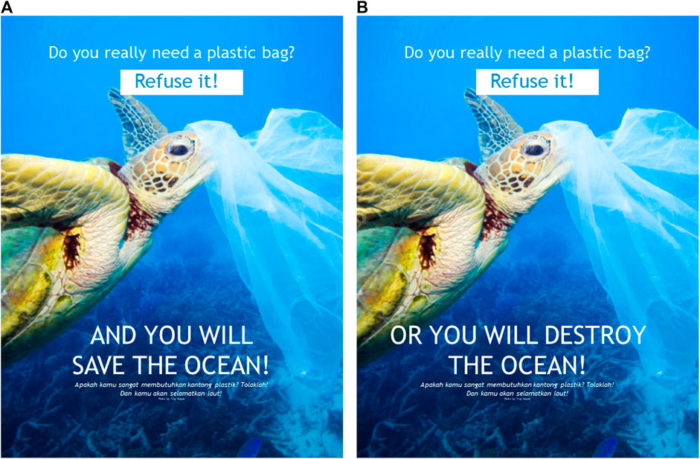

This sounds great, but do nudges work? Sort of. The current study looks at two things, the first being whether or not people accept or refuse a plastic bad at the check-out of a store. They compared three conditions, a passive nudge (a sign) message that was positive (“refuse a plastic bag and you will save the ocean”), a similar but negative message (“refuse a plastic bag or you will destroy the ocean”), and a no-intervention control group. People were also either asked if they needed a plastic bag or not, so there were six groups in total. They found:

The largest proportion of people who actively refused plastic bags were found under T1 (positive and asking) with 58.06% and the lowest proportion of people who refused plastic bags were exposed to T6 (no sign and not asking) with 30.03%.

Whether or not the clerk asked if they needed a plastic bag was a bigger factor than the signs. There was not much difference between positive and negative messaging, but positive was a little better. That is a fairly robust effect size comparing the two extreme ends. These are also both very easy and low-cost interventions – put up a sign with a positive message encouraging responsible behavior, and train workers to do simple things that beneficially affect customer behavior. Customers still have full choice, and there are no consequences of doing whatever you want.

These are no-brainer interventions, and in many cases can cost nothing. Often nudging simply amounts to making the more responsible decision the default decision. Rather than asking every customer, “Do you want to supersize that?” make the normal size meal the default. People can still supersize if they want, however. It’s also not surprising that the biggest effect was simply asking customers if they wanted a plastic bag, rather than just reaching for it and leaving it up to the customer to chime in and refuse.

There may be those who still feel that even nudges are unwanted because they are manipulative, and they don’t want to be manipulated by Big Brother, herded like sheep into politically correct behavior. What this attitude ignores, however, is that you are always being nudged, whether it is deliberate or not. Human behavior (in the short term) is remarkably malleable. We respond to social cues, and to implicit messaging. (Affecting long term behavior is a different beast, and is remarkably difficult.) The real question is – is the nudging unintentional and harmful, intentional and harmful, or intentional and beneficial (or neutral or some other permutation)? Yes, that does mean that someone has to decide what beneficial is, but someone is often deciding that for you whether you know it or not. When you walk into a store you are being nudged in many ways, in order to influence your purchasing decisions – in a way that is beneficial to the store, not you.

There is a lot of complexity here, but saying that you don’t want anything to influence your behavior is not realistic. Rather, I personally think the best approach is balance, transparency, ethics, and evidence-based. By balance I mean different sectors of society have some portion of power in terms of deciding how the public gets nudged. Corporations have a measure of control, but so does the government, and citizen groups, and all under the eye of the press. A balance of power is often a good default approach – dystopian visions of the future often involve one segment of society totally taking over. Nudging campaigns, like any system of influencing or controlling behavior, needs to be transparent (no hidden-agendas), and subject to some kind of review. Ethical considerations, such as respecting individual liberty, also need to be met. And finally, whenever possible, scientific evidence should be used to measure the effect of any such campaigns.

Obviously there is lots of low hanging fruit here. Hanging a sign with explicit messaging is transparent. There are many things that we can agree upon as a society are good things, like not destroying the environment, not driving while drunk, not exposing children to poison, etc. Often encouraging good behavior is simply a matter of reminding people at the point of decision-making to do the responsible thing. Oh yeah, right, I shouldn’t put poison in an open cabinet in reach of my toddler. That seems obvious, but there are thousands of such obvious things in our daily lives, and we can’t always remember them all. Having some nudging guardrails actually can make life easier. It reduces our mental load, and helps us do the things we would want to do anyway if we had the time to really think about it. Nudging are a good default approach because they are cheap, they can be effective, and they do not limit liberty. They are, in fact, a way of preserving liberty – because without them, taking more draconian steps becomes more likely.