Apr 10 2018

More Evidence Against Learning Styles

Are you a visual learner or an auditory learner? Perhaps you learn best when studying material hands on. Or perhaps it doesn’t matter, and the entire concept of different people having different learning styles is not valid.

Are you a visual learner or an auditory learner? Perhaps you learn best when studying material hands on. Or perhaps it doesn’t matter, and the entire concept of different people having different learning styles is not valid.

A new study adds to the pile of those that find little evidence to support the notion of learning styles, but we’ll get to that shortly.

The basic concept is that different people have different strengths and weaknesses that relate directly to how well they learn new information. Further, these strengths and weaknesses can be codified into specific styles, that can then be measured in some valid way. Finally, if you teach a student material in their preferred style, their outcomes will be superior to if they are taught the same material in a manner not in line with their preferred style.

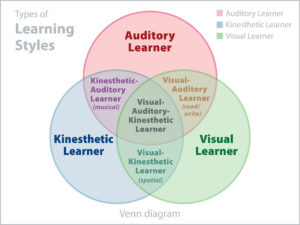

Layered on top of this basic concept are different hypothesized schemes of learning styles – different ways to break up learning strategies. There are visual vs verbal learners, or perhaps abstract vs personal, more or less interactive, problem-solving, etc. One researcher estimated that there are more permutations of different learning styles than there are people on Earth. So really we have to ask – is the basic concept of learning styles valid, and if so which learning style scheme is more helpful?

The answer appears to be no and none.

Despite this lack of convincing evidence, the notion of learning styles remains popular. A 2017 survey found that 53% of teachers in higher education endorsed the concept of learning styles, but this support has been waning as more and more negative evidence comes in.

Part of the reason for lingering support is that the concept is appealing. There is a general intellectual bias toward simplicity – all things considered, we would prefer if the world were simple and manageable. Humans are therefore very inventive when it comes to devising schemes that package the world into bite-sized and easily categorizable chunks.

To some extend this is OK, as long as we recognize that such categories are schematic – a deliberate oversimplification in order to highlight important features. Confusing a simplified schematic for reality is problematic, however. It is far worse if the schematic does not reflect important features, but imaginary, ephemeral, or insignificant ones.

Lingering belief is also likely due to the fact that evidence for a lack of something is never as convincing as evidence for the existence of something. This is partly logical – lack of evidence is only as compelling as the thoroughness, sensitivity, and appropriateness of the efforts made to look for evidence. Such considerations take a lot of objective judgement, and we are not inherently good at such things.

Humans excel, however, at special pleading – making up creative excuses for the lack of evidence. So proponents of learning styles argue that the evidence so far is negative because the studies have not been good enough. They did not account for learning outside the classroom. They did not use the proper scheme of styles. They didn’t use good enough learning methods, or the subject matter was biased toward one method, etc.

The thing to realize about special pleading is that the individual points are not necessarily wrong or unreasonable. Rather, the fact that we can think of a reason why evidence is lacking is not very predictive, because of our cleverness in inventing such reasons. We can always find an excuse, so the existence of an excuse doesn’t say much.

This is where judgement comes in. You have to look at the overall picture, the arc of the research, and the relationship between rigor and outcome. In this case the hypothesis that different students have different learning styles has not been useful or predictive. Many reasonable criticisms have been dealt with, and the evidence is still largely negative.

At some point we cross the threshold where it is reasonable to conclude that an idea is an intellectual dead end. It seems that we are past that threshold with the concept of learning styles – even before the more recent study, which just reinforces that conclusion.

In the new study the researchers looked at 426 anatomy students from the 2015 and 2016. They divided them into groups based upon a standard test of learning styles (VARK test). They then instructed them on how to study according to their learning style, and this applied both inside and outside of the classroom to address the complaint that learning outside the class obscures any effect inside the class.

The researchers found that most students did not comply with the learning style they tested for according to VARK. Further, whether they did or not had no effect on their final grade in the course. Some learning strategies were more successful than others, such as using the virtual microscope. But, these successful strategies correlated with a better outcome regardless of the VARK score – so again, it did not matter what the students’ supposed learning style was.

As always I have to point out that this is just one study, but it does add to the consensus of the literature that learning styles does not seem to be a useful concept.

At this point what I think we can conclude from the evidence (and this is in line with what seems to be the consensus from reading various reviews), is that for most students trying to determine and then cater to their alleged learning style is not useful. I say “most” students because the evidence tends to focus on students who do not have special needs. If, for example, one student has very low reading ability, then their learning through reading will be impaired. So none of my comments in this article really apply to students who require an individualized learning program, but rather to so-called “mainstreamed” students.

With that caveat, the entire concept of learning styles should probably be abandoned.

Rather, it seems, learning strategies that work, work regardless of the student. It seems to be much more useful to tailor learning strategies to the material, if anything. Anatomy is a very visual subject, for example, and so visual or hands-on strategies will probably work better than purely verbal strategies. By contrast, verbal strategies may work better in a philosophy class.

The evidence also suggests that using different media work better than using one media type. Learning is also enhanced by active problem solving and interacting with the material. Learning is perhaps most enhanced by teaching. And the optimal mix of these strategies probably varies by not only subject but advancement. Beginning courses for young students may need to be more passive, and then become progressively more interactive as they advance.

So focusing on the material, the relative advancement, and strategies that are inherently superior, seems to be a much more pragmatic and useful approach than chasing the apparent myth of individual learning styles. Even if you want to use special pleading to be a hold-out for the basic concept of learning styles, you have to admit that the evidence does not support its effectiveness in the real world. Any possible remaining effect is likely too small to worry about.