Jan 08 2019

Misunderstanding Dunning-Kruger

There is, apparently, an increase recently in interest in the Dunning-Kruger effect. The Washington Post writes about this recently, making the obvious political observation (having to do with the current occupant of the White House). It’s great that there is public interest in an important psychological phenomenon, one central to critical thinking. I have discussed DK before, and even dedicated an entire chapter to discussing it in my book.

There is, apparently, an increase recently in interest in the Dunning-Kruger effect. The Washington Post writes about this recently, making the obvious political observation (having to do with the current occupant of the White House). It’s great that there is public interest in an important psychological phenomenon, one central to critical thinking. I have discussed DK before, and even dedicated an entire chapter to discussing it in my book.

Unfortunately the Post misinterpret the DK effect in the common way that it is most often misinterpreted. They write:

Put simply, incompetent people think they know more than they really do, and they tend to be more boastful about it.

and

Time after time, no matter the subject, the people who did poorly on the tests ranked their competence much higher. On average, test takers who scored as low as the 10th percentile ranked themselves near the 70th percentile. Those least likely to know what they were talking about believed they knew as much as the experts.

The first sentence makes it seem like the DK effect applies only to people who are “incompetent.” This is wrong on two levels. The first is that the DK effect does not apply only to “incompetent people” but to everyone, with respect to any area of knowledge. To be fair the author also writes, “it is present in everybody to some extent,” but this does not really capture the reality, and is undone by the sentences above. Second, the effect applies not just in the range of incompetence, but even for average or moderately above average competence.

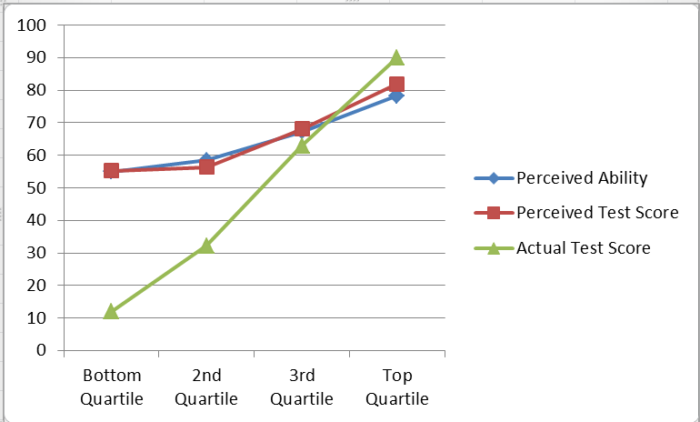

The graph tells it all. The best way to summarize the data is to say that the difference between self-assessment and performance increases with lower performance below about the 80th percentile, with slight underestimation of performance for those above the 80th percentile (or a test score of about 70%). So almost everyone overestimates their performance, not just those who are “incompetent.” Even if you scored 60% correct and were in the 75% percentile, you overestimated your ability a little.

Further I need to emphasize that the data does not apply to “people” who are generally in the low percentiles of competence, but to everyone with respect to where they are with each individual area of knowledge. So the same person may be in the 80th percentile in one knowledge area, and the 20th percentile in another, and the graph above applies to them in both cases.

Having said that I want to point out that these are average scores. Individuals will vary in terms of how humble or boastful they are, depending on basic personality, training, insight, and experience. That, in fact, is my primary point in discussing the DK effect and making sure it is properly understood. The goal is to provide critical thinking insight, so that people will generally be more self-aware and humble in assessing their own knowledge and abilities, to offset the general tendency toward overconfidence.

The author’s second paragraph above doubles-down on the primary misunderstanding that the effect applies to people who “did poorly on the tests,” when, as I pointed out, it applies to everyone below about the 80th percentile. Also, those at the lower end of performance did not rank themselves as highly as experts, but rather ranked themselves as being a little above average (but still lower than people who performed better). This is consistent with other research, which shows that people generally think they are above average pretty much in everything. We seem to have a hard time admitting that we are below average in any ability or area of knowledge.

I know this all may seem like nitpicking, but it is important to how the DK effect is interpreted. The vast majority of people who bring it up seem to think that it applies only to dumb people and that it says dumb people think they are smarter than smart people. Neither of these things are true. Further – if you think it only applies to other people (which itself, ironically, is part of the DK effect) then you miss the core lesson and opportunity for self-improvement and critical thinking.

There are some nuances to the DK effect also worth discussing. While the core effect is as I described above, which characterizes average scores, other research shows that specific individuals and specific topics have their own curves. For example a recent study shows that those who endorse anti-vaccine views were far more likely to estimate that they knew as much as experts or doctors, when in fact their knowledge level was extremely low.

Research is ongoing as to the causes of the DK effect. It is partly a generic overconfidence effect, but that is not all. Dunning believes that ability to self-assess is also key to the effect. Essentially – when you lack knowledge in an area you do not know what you don’t know, you lack the knowledge to assess your own knowledge and the knowledge of others. This may have its own curve. In other words, as you gain knowledge about a topic at first that small amount of knowledge may give you great confidence. It will certainly seem like a huge amount of knowledge compared to your previous complete ignorance (a Sophomore effect). As you gain knowledge, this confidence grows. Only at relatively high levels of knowledge do you begin to realize how much there is to know, and how much real experts know.

This is exactly why I encourage everyone to think about and extrapolate from their experience in topics that they know a great deal about – where they are likely to be above the 80% percentile. In areas where you have legitimate expertise, you understand how much deep knowledge there is, and how little the average person knows. Well – the same is generally true about all areas of knowledge, and you should use that to recalibrate your assessment of your relative knowledge in those areas. In other words – you are probably as ignorant in areas of knowledge where you are not expert as you think other people are in areas of knowledge where you are expert.

Finally, there are personality traits that seem to modify the DK effect. Specifically, narcissistic personality seems to put DK on steroids. These are people who generally have poor knowledge, greatly overestimate their knowledge, and are least open to accepting criticism and self-correction. This brings us back to the Washington Post article, and you can draw your own conclusions there.