May 29 2020

The Learning Styles Myth

I have written previously about the fact that the scientific evidence does not support the notion that different people have different inherent learning styles. Despite this fact, the concept remains popular, not only in popular culture but among educators. For fun a took the learning style self test at educationplanner.org. It was complete nonsense. I felt my answer to all the forced-choice questions was “it depends.” In the end I scored 35% visual, 35% auditory, and 30% kinesthetic, from which the site concluded I was a visual-auditory learner.

about the fact that the scientific evidence does not support the notion that different people have different inherent learning styles. Despite this fact, the concept remains popular, not only in popular culture but among educators. For fun a took the learning style self test at educationplanner.org. It was complete nonsense. I felt my answer to all the forced-choice questions was “it depends.” In the end I scored 35% visual, 35% auditory, and 30% kinesthetic, from which the site concluded I was a visual-auditory learner.

Clearly we need to do a better job of getting the word out there – forget learning styles, it’s a dead end. The Yale Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning has done a nice job of summarizing why learning styles is a myth, and makes a strong case for why the concept is counterproductive.

The idea is that individual people learn better if the material is presented in a style, format, or context that fits best with their preferences. The idea is appealing because, first, everyone likes to think about themselves and have something to identify with. But also it gives educators the feeling that they can get an edge by applying a simple scheme to their teaching. I also frequently find it is a convenient excuse for lack of engagement with material.

There are countless schemes for separating the world into a limited number of learning styles. Perhaps the most popular is visual, auditory, vs kinesthetic. But there are many, and the Yale site lists the most popular. They include things such as globalists vs. analysts, assimilators vs. accommodators, imaginative vs. analytic learners, non-committers vs. plungers. If you think this is all sounding like an exercise in false dichotomies, I agree.

Regardless of why people find the notion appealing, or which system you prefer, the bottom line is that the basic concept of learning styles is simply not supported by scientific evidence.

I find it all very similar to the literature on personality types (as opposed to traits). There are many simplistic schemes for dividing the world into a very limited number of archetypes, but the scientific evidence supports none of them, and indicates that the very notion of personality types is probably false.

I like the fact, though, that the Yale site goes beyond documenting that the notion of learning styles is a scientific dead end and needs to be abandoned. They also illustrate that we have scientific evidence supporting some actually useful ideas in education, but they tend to be overshadowed by the learning style myth. This all reminds me of the book 59 seconds by Richard Wiseman. He points out that there is a vast self-help industry largely selling myths and nonsense. But perhaps more importantly, there is a vast psychological literature out there with actual helpful knowledge that the self-help industry ignores. Likely, many educators get distracted by the myth of learning styles and neglect what the science has to teach us about optimizing teaching.

Perhaps the most important concept, from my perspective, is the fact that different learning approaches (visual, auditory, or tactile, for example) are both complementary and more or less effective depending on the subject matter. So first, teachers should embrace a multimedia approach to teaching by default. The more different ways student interact with information, the better than will learn and retain it.

But also – the type of media should, if anything, be aligned with the subject matter, not the student. If, for example, you want to learn about anatomy, visual information is going to be superior to auditory only information – for everyone. But then reading or listening can help students understand what they are looking at, highlight key concepts, and reinforce the most important bits of information.

There is also data supporting other aspects of the learning experience, such as it being interactive, giving immediate feedback, and also getting students to engage with teaching each other. The data clearly shows that the most effective way to learn material is to have to teach it to someone else. Students also benefit from reflecting on the process of learning itself.

So teachers should be focusing on presenting material in multiple ways, getting students to interact with the material and the learning process, and also matching the way the material is presented to the subject area. This, of course, can be a lot of work. It’s easier just to give students a 20 question BS survey, then label them and cater to that simplistic label.

If teachers want to take an individual approach to students, which I am not arguing against, that individual approach should focus on teaching learning and studying skills. Different students might prefer and work better with different approaches to studying material and getting the work done. Students may also have different barriers to learning that need to be addressed. Part of the learning process is to learn how to learn, and that is where some individualization is probably helpful.

But even here, for most students (some students do require individualized learning plans because of special needs, so that is a different case) generic studying skills are likely to serve most students well. For example, we know from scientific studies how memory generally works. If you want to remember material, then it is best to study it over and over, with increasing delays in between. Repetition is key, but the timing can also be optimized. Teaching students to study smart, and to evaluate the effectiveness of their own studying, is extremely useful.

Education is complicated, and involves many layers. I think everyone would agree that a good goal is to make the teaching and learning process and efficient and effective as possible. To do that we need to listen to the scientific evidence. This does happen to some degree, but often this process itself is inefficient. The myth that there are different learning styles and that teachers should cater to the learning styles of different students is perhaps the best example of the disconnect between the scientific evidence and the everyday practice of educators, and also popular belief. It is counterproductive because it distracts from the growing body of scientific evidence that provides actually useful tips for more effective teaching.

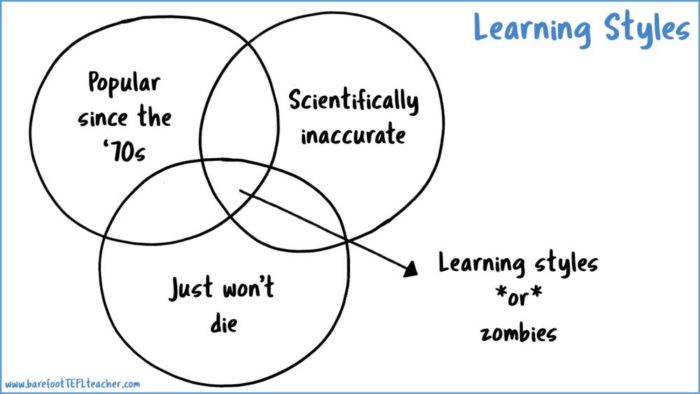

The question is – how do we finally kill this myth? It has proven to be stubbornly persistent.