Jul 25 2019

The Global Warming Consensus

The degree to which there is a scientific consensus in anthropogenic global warming (AGW) remains politically controversial, even though it is not scientifically controversial. Denial of the consensus remains a cornerstone of AGW denial, so let’s examine the science and the arguments used to deny it.

The degree to which there is a scientific consensus in anthropogenic global warming (AGW) remains politically controversial, even though it is not scientifically controversial. Denial of the consensus remains a cornerstone of AGW denial, so let’s examine the science and the arguments used to deny it.

Much of the public discussion focusses on the 2013 Cook article which claimed that there is a 97% consensus among experts in AGW. This has become the poster child of the consensus argument, much in the way Mann’s original article has become the icon of the “hockey stick” of global temperatures. The denialist strategy here is the same – falsely present the situation as if all the scientific eggs are in one basket, and then attack that basket with everything you have.

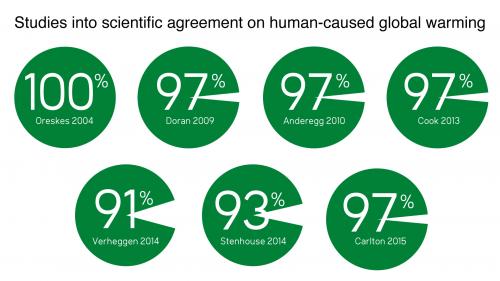

So Cook has been vilified by the deniers as if that demolishes the evidence for a consensus. That strategy ignores, however, the many other studies that also look at the question of consensus. In fact, there is a consensus of studies on consensus. A 2016 review of 6 independent studies found the range of estimates of the consensus is from 90-100%, with the consensus clustering around 97%. The “everything depends on that one Cook study” strategy is just factually incorrect.

The other strategy used to deny the consensus is to misrepresent individual studies, again with the focus being on Cook. There is admittedly a lot of complexity here, and no one number will capture that. No individual study is perfect, because you always have to make some trade-offs. These papers are all estimates of the consensus, and had to make certain assumptions. But that is why multiple independent estimates are useful.

Here is an example of a typical criticism of the Cook study, which concludes that the real consensus is only 1.6%, a stark difference. Cook looked at abstracts of published peer-reviewed studies on climate change and categorized them as:

1,Explicitly endorses and quantifies AGW as 50+% : 64

2,Explicitly endorses but does not quantify or minimize: 922

3,Implicitly endorses AGW without minimizing it: 2910

4,No Position: 7970

5,Implicitly minimizes/rejects AGW: 54

6,Explicitly minimizes/rejects AGW but does not quantify: 15

7,Explicitly minimizes/rejects AGW as less than 50%: 9

That is a reasonable breakdown, but you can already see the complexity. When we talk about a consensus on AGW we have to further ask exactly what scientists believe – that the Earth is warming, that human activity is forcing this warming, that human activity is the main factor forcing warming, or that the consequences will be more negative than positive.

The 97% figure in the Cook article is those abstracts that explicitly or implicitly endorsed AGW and either said it was 50+% caused by human activity, or did not quantify or minimize the human contribution. This excludes abstracts that expressed no position. The complexity here allows for a lot of motivated quibbling. Should we include abstracts that don’t express an opinion? (I think the only reasonable answer is no, and Cook points out that if you did a similar analysis of other solid scientific positions the results would be the same.) Also, what do those scientists who endorse AGW and don’t minimize the human contribution but also don’t explicitly quantify it actually believe? Do some of them believe AGW is real but the human contribution is minor?

Henderson, in the linked criticism of Cook, criticizes Cook for assuming they all agree the human contribution is significant, but then comes to his own 1.6% figure by assuming that none of them think it’s significant.

In any case – what we can say from the Cook study is that 97% of climate experts who expressed an opinion agree that the globe is warming and humans are at least partly responsible. You can then quibble about to what extent humans are playing a role, and what the consequences will be, but you have to at least acknowledge what the Cook study undeniably found.

And of course this is not the only study. There are studies that directly ask climate experts what they think. For example, Carlton et al 2014 paper asked climate experts the following:

Response to the following: (1) When compared with pre-1800’s levels, do you think that mean global temperatures have generally risen, fallen, or remained relatively constant, and (2) Do you think human activity is a significant contributing factor in changing mean global temperatures?

Of those surveyed 97% agreed the Earth is warming and human activity is a significant contributing factor.

In trying to understand the consensus we can also ask other questions – what is the relationship between degree of expertise and agreement in AGW, and how is the consensus changing over time. The evidence shows that the greater the level of expertise, the greater the percentage of endorsement. Further, if anything, the consensus is strengthening over time.

Another way to estimate a consensus about a scientific question is to see what scientific organizations officially say. Such organizations often put together expert panels to review the evidence and come to a consensus, and then put out a position paper with the results. NASA lists 18 such organizations that explicitly endorse the consensus on AGW.

As I often state, in order to understand what the scientific evidence on a question really says you need to understand the arc of the research – as questions arise and are addressed, as other ways of looking at the data are explored, and as studies are replicated – do the findings get more robust, or less clear? The trend in AGW research has been clearly toward the more robust end of the spectrum.

Three recent studies highlight this trend. In one study the authors show that over the lat 2,000 years there has been no spatially and temporally coherent climate change event. What this means is that natural trends in climate result in changes in average temperatures, but only regionally and only for a limited time. At no point in this time frame did the entire globe either warm or cool over decades – that is, until the industrial period. The current trend of truly global warming is therefore unique in the last 2,000 years.

The other two papers also involve reconstructions of climate over this time period and show that the little ice age was largely due to forcing by volcanic eruptions, and the other shows consistency of various models and methods of estimating historical temperatures over multi-decadal timescales.

Again – no one study is definitive. But as more evidence comes in, as new ways of looking at the data are considered, the consensus of evidence and expert opinion that AGW is real and significant strengthens.

Deniers always try to portray theories they don’t like as on the brink of collapse, as a house of cards that will blow over in the slightest wind. Creationists say this about evolutionary theory, for example. But the truth belies these fictions. The consensus on AGW is real and robust, and the trend in scientific evidence is only getting stronger.

Does this mean the science is “settled.” That is actually not the question, and in fact is a silly semantic distraction from the science itself. Science is a never-ending process, and is never 100% settled. But that is irrelevant. The question, rather, is when is a scientific theory sufficiently established that we can treat it as a fact?

When it comes to policy the question is best framed as – when is there sufficient evidence to form a basis for policy? When framed properly, this question regarding AGW is pretty clear. There is strong enough evidence and a solid enough consensus of experts and scientific institutions to base policy on the tentative conclusion that AGW is real, human contributions are significant, and the results are likely to be costly and net harmful.