Apr 22 2019

Partially Reviving Dead Pig Brains

I turns out they were only “mostly dead.” Well, it depends on your definition of death.

I turns out they were only “mostly dead.” Well, it depends on your definition of death.

This is an interesting study that has been widely reported, with a surprisingly small amount of hype. The New York Times writes:

‘Partly Alive’: Scientists Revive Cells in Brains From Dead Pigs

In a study that upends assumptions about brain death, researchers brought some cells back to life — or something like it.

All the reporting I have seen so far has appropriate caveats, but they are really trying hard to maximize the sensational aspects of this study. I actually wrote about this study one year ago when the data was first presented. Now it has been published, so there is another round of reporting (which interestingly ignores the prior reporting).

The quick version is that Yale neuroscientists collected decapitated pig brains four hours after death and then tried to keep the brain cells alive in order to see what would happen. It’s actually a great real-life Frankenstein type experiment, a fact not missed by some outlets. Here is what they did:

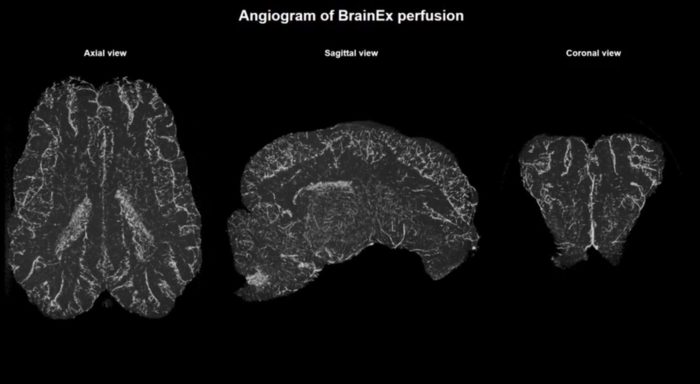

We have developed an extracorporeal pulsatile-perfusion system and a haemoglobin-based, acellular, non-coagulative, echogenic, and cytoprotective perfusate that promotes recovery from anoxia, reduces reperfusion injury, prevents oedema, and metabolically supports the energy requirements of the brain.

So they basically gave it artificial blood in a pulsatile fashion, like a beating heart. They perfused the brains with nutrients, oxygen, and also drugs to minimize the processes that happen after death. They found:

With this system, we observed preservation of cytoarchitecture; attenuation of cell death; and restoration of vascular dilatory and glial inflammatory responses, spontaneous synaptic activity, and active cerebral metabolism in the absence of global electrocorticographic activity.

What this basically means is that some cell function was still able to be active, and the small blood vessels were intact enough to allow for the perfusion of the brain. However they did not see any evidence of the kind of electrical activity that a living brain would produce. They were also giving the brains a sedative to make sure, in an excess of ethical caution, that the pig brains did not regain even a flicker of conscious awareness.

Were these pig brains alive? No, not in any meaningful sense. When an animal dies, that usually means their heart stops beating (not counting brain death patients where the heart is still going) and all major functions of the body also stop. However, the cells in the body do not instantly die. They take minutes to hours to die. By 72 hours pretty much all the cells are dead.

So it is not surprising or “stunning” or any of the other hype words that the press is using to find that four hours after death there are cells in the body that are still clinging to life. It is a little surprising that brain cells are alive after four hours, because the brain is especially susceptible to a lack of oxygen and brain damage starts to occur within a few minutes of interruption of blood flow.

What this does mean is that the process of brain cell death is longer and more complicated than we previously appreciated. There are still some functions occurring even after four hours, and these can be maintained at least for a little while by providing oxygen and nutrients. But these flickers of cell activity were not nearly enough for the brain cells to actually function. Those pigs were brain dead and nothing the researchers did changed that.

What this research does mean is that it takes at least four hours for all aspects of brain cell function to completely stop after death. This gives scientists the potential opportunity to study the brain in greater detail, by keeping the brain going for a little bit before it turns to mush. Certainly we can learn more about the process of brain cell death itself, and who knows if there will be any fallout from this information. Best case, it may lead to an experimental model for treating brains after stroke or cardiac arrest to reduce damage or promote recovery.

Most of the reporting did a fair job of getting this aspect of the study correct. Where the hype came in mostly was about “redefining life and death.” There already was a fuzzy boundary between life and death, and I don’t think this study does anything to change that. These pigs were only “partly alive” in the same way that all animals are still “partly alive” four hours after they die. Some of their cells are still alive until the cell death phase is complete.

We also can already bring people back from the dead in that we can restart their hearts, and we have treatments to minimize cell damage in such cases. If we get to people quickly enough, and do CPR to get at least some blood flow to their vulnerable brain, we can bring people back. The longer they are out, the more damage there is, however. Prolonged CPR, more than 20-30 minutes, has a terrible prognosis for recovery.

The study does raise the interesting question of the ethics of doing research on intact brains in which the cells are still alive. These pig brains did not get anywhere close to having consciousness, and I don’t think the sedatives were necessary but a follow up study would be necessary to definitively demonstrate that. But it is not inconceivable, if brains are harvested immediately after death, for example, and the technology to provide artificial life support improves, that there may be a day that we can keep a pig brain alive in a vat with sufficient activity that it can be conscious on some level.

The legitimate question is – what are the ethics of doing just that, of keeping brains alive and functional enough to be conscious outside their bodies? I don’t think we are close to that situation, but it is not a bad idea to have the conversation before we are. We have to be careful, however, not to be so overly cautious that we stifle valid and ethical research.

I do think we need to assume that being an extracorporeal awake brain would not be a pleasant experience. Who knows, but it may certainly be cruel in the extreme, meanwhile we would have no real way of knowing. The good news is that we can easily monitor electrical activity (with an EEG) and make sure any extracorporeal brains, even if they are alive at a cellular level, are permanently asleep or comatose.

So while this study is extremely interesting, it is not the game-changer the media would have us believe in terms of life and death. But it does point to future research in which we may need to develop new ethical rules for researchers.