Mar 07 2022

Alcohol Is Bad for the Brain

The dose makes the poison, so anything is potentially a poison in a high enough dose and safe in a low enough dose. But we generally refer to substances as poisons or poisonous if they cause significantly negative or dangerous biological effects at typically encountered doses. By this practical definition, alcohol is a poison. When you are tipsy or drunk what you are experiencing is alcohol’s poisonous effect on the functioning of your brain. The acute effect of alcohol is to inhibit neuronal firing, thereby depressing brain function. Even after one drink, these effects can be measured in reduced reaction time and cognitive function.

The dose makes the poison, so anything is potentially a poison in a high enough dose and safe in a low enough dose. But we generally refer to substances as poisons or poisonous if they cause significantly negative or dangerous biological effects at typically encountered doses. By this practical definition, alcohol is a poison. When you are tipsy or drunk what you are experiencing is alcohol’s poisonous effect on the functioning of your brain. The acute effect of alcohol is to inhibit neuronal firing, thereby depressing brain function. Even after one drink, these effects can be measured in reduced reaction time and cognitive function.

There has long been a scientific question, however, as to how much of a long term damaging effect alcohol has on the brain. It’s possible that it acutely inhibits neuronal firing, but once out of your system, function returns to normal and no harm done. There is a great deal of scientific research on this question, which has well-established that chronic heavy alcohol use causes damage to the brain. Even after we separate out damage caused by associated malnutrition (vitamin B1 being most relevant) there is a separate direct brain toxicity from heavy alcohol use.

While this is scientifically settled, there is still the question of – at what amount of regular alcohol use does this damage begin? The evidence for brain damage from light to moderate drinking has been mixed. This makes sense just from a statistical point of view. As we look at milder exposure, effect sizes should decrease and eventually be lost in the noise. So generally speaking, with any phenomenon, it should be easier to see with the strong effect size, then the scientific results should become mixed and ambiguous with smaller effects sizes, and then eventually disappear. This would be true even if the toxicity from alcohol were strictly linear with no threshold.

That, of course, is a separate question – is there is lower threshold for this long term toxic effect of alcohol on the brain? Does a little bit of alcohol cause a little bit of damage, or is there a threshold below which there is no damage? Also, toxicity may be non-linear. It might increase, for example, geometrically. Perhaps doubling exposure does not double damage, but multiplies it by four. There may then be an inflection point when present but insignificant damage rapidly turns into very significant damage. There is likely also cofactors, underlying conditions that may magnify the damage done by alcohol (such as age, other causes of brain damage, malnutritioon, etc.).

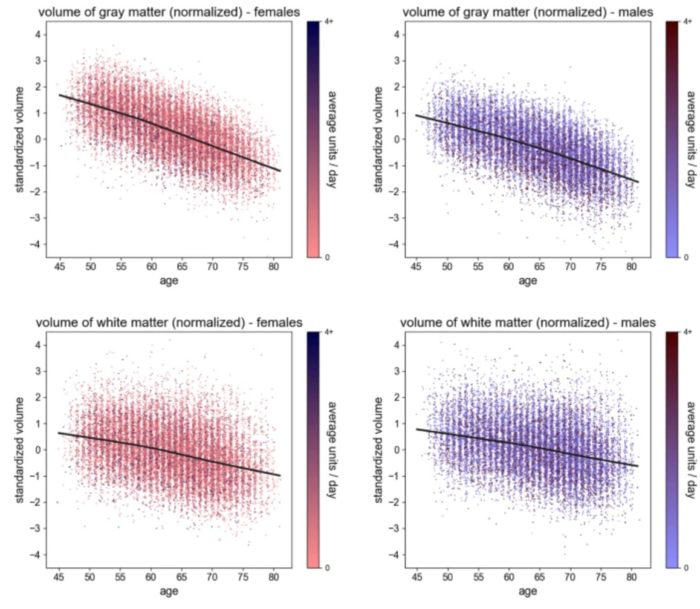

These questions have to be asked and examined for each substance. How do we explore the lower limit of toxicity? The short answer is, through more powerful studies. The higher the power of the study, which is essentially a result of the number of subjects in a study, the smaller an effect size we can detect with statistical significance. That is exactly what has now happened in terms of the effects of alcohol on the brain. Researchers Daviet et. al. published in Nature Communications a study that looks at “36,678 generally healthy middle-aged and older adults from the UK Biobank.” They looked at overall brain volume, gray matter volume and structure, and white matter structure in the brains of subjects in the data base and compared that to their average daily alcohol consumption. They used “units” of alcohol, with one unit being equivalent to half a beer or glass of wine, so two units is one drink.

They also controlled for a host of possible confounding factors: age, height, handedness, sex, smoking status, socioeconomic status, genetic ancestry, and county of residence. Essentially for each individual they predicted what their brain volume should be based on all these other factors, then compared that to its actual measurements and average alcohol consumption. What they found was a negative correlation between alcohol consumption and brain volume, for even as little as one drink (two units) per day. There was no difference between zero and one units, but there was a statistical difference between zero and two. This negative correlation held up across the study, so there was a clear dose-response curve, which supports a causal interpretation. To put the findings into some biological context, they compared the apparent effect of alcohol to that of age. Having one drink per day made the brain look six months older. Having four drinks per day made the brain look 10 years older.

These results also mean that the toxic effects of alcohol are non-linear. They increase geometrically as total exposure increases. So each additional unit of alcohol consumed each day had a greater negative effect on brain volumes than the previous unit. This study does not answer the question of whether or not there is a lower threshold where any damage kicks in. But at the very low end there is a distinction without much difference – undetectable damage, even in a high powered study, may not be clinically significantly different than no damage.

It must be pointed out that this study is correlational only, and therefore cannot be used to draw firm conclusions about cause and effect. That is often the trade-off – in order to get very high power, you have to sacrifice something, in this case subjects were not randomized to their alcohol consumption. That would be an ethically dubious study anyway. But, in an observational study we can control for possible confounding factors, as they did here. There is still the possibility that there is an unknown confounding factor, but the more a question is researched the lower the probability of such a hidden factor. Also, as I stated, the consistent dose-response curse favors a causal interpretation.

In any case, this one study, while powerful, is not the final word. We need replication with different datasets. Also, it would be nice to look at other variables, such as the difference between drinking one drink per day and seven drinks on the weekend. What we can say with all the existing data, however, is that heavy alcohol use causes brain damage. Moderate alcohol use probably causes milder brain damage, and there is a suggestion that this effect extends into even mild alcohol use but our confidence decreases at the milder end of this spectrum. Individuals can use this information to make decisions for themselves regarding how much risk they are willing to take in terms of healthy brain aging.