Mar 28 2019

Robotic Pets

I warn frequently about the folly of trying to predict the future. Obviously we need to do this to some extent, but we always need to be aware of how difficult it is. It is especially hard to predict how people will use technology, even if the technology itself is inevitable. Until devices are in the hands of actual people out there in the world, who try to incorporate the tech into their daily lives, we just can’t know how it is going to shake out.

I warn frequently about the folly of trying to predict the future. Obviously we need to do this to some extent, but we always need to be aware of how difficult it is. It is especially hard to predict how people will use technology, even if the technology itself is inevitable. Until devices are in the hands of actual people out there in the world, who try to incorporate the tech into their daily lives, we just can’t know how it is going to shake out.

So, having said that, I am going to make a prediction about how people are going to incorporate future technology. I think robotic pets are going to be increasingly popular as the technology advances. At least I am going to build what I think is a strong case for this prediction. The risk is that there is something I cannot anticipate that will be a deal-killer. Feel free to try to shoot this down and bring up points, but hear me out first.

From a neurological point of view, I do not see any obstacle to people bonding fully with robotic pets. Neuroscience has clearly established that the human brain has certain algorithms that it uses to assign emotional significance to things, to form emotional attachments, and to respond to emotional signaling. In order for the full suite of emotional responses to be in play, being alive is simply not required. That is not how our brains work.

Our visual systems, for example, sort the world into two categories – things that have agency, and things that do not have agency. Having agency means that our brains infer that they are able to act with their own will and purpose. They infer this from how objects move. If they move in a way that cannot be explained simply as passive movement within an inertial frame of reference, then they must be moving on their own. Therefore they have agency.

Every time I heard someone use the term “witch hunt” recently I was reminded of that quote from Indigo Montoya from The Princess Bride – “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.” With the recent release of the Mueller report, many news outlets feel obliged to interview people on the street about their opinions. This is an inane practice that provides no useful information, just cherry-picks random opinions. Every single time I heard the term “witch hunt”, it was used incorrectly.

Every time I heard someone use the term “witch hunt” recently I was reminded of that quote from Indigo Montoya from The Princess Bride – “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.” With the recent release of the Mueller report, many news outlets feel obliged to interview people on the street about their opinions. This is an inane practice that provides no useful information, just cherry-picks random opinions. Every single time I heard the term “witch hunt”, it was used incorrectly. It’s refreshing to encounter a well-researched piece of excellent journalism that is not afraid to communicate an accurate picture of the subject. The headline of this article reads, “

It’s refreshing to encounter a well-researched piece of excellent journalism that is not afraid to communicate an accurate picture of the subject. The headline of this article reads, “

Marcelo Gleiser is an astrophysicist and science popularizer. I have not read any of his works previously and was therefore not familiar with him. He recently won

Marcelo Gleiser is an astrophysicist and science popularizer. I have not read any of his works previously and was therefore not familiar with him. He recently won  One of the core concepts in my book,

One of the core concepts in my book,

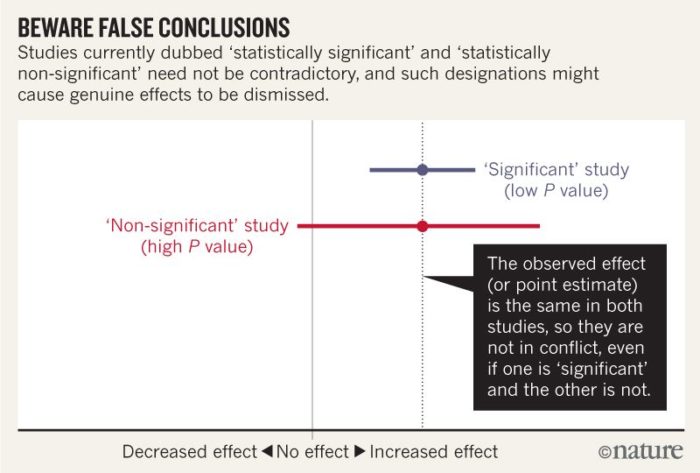

As a physician you have to develop a certain comfort level with uncertainty. The simple fact is – we don’t know everything. The human body is extremely complex, and there are over 7 billion people on the planet representing a great deal of variation. Our data is incomplete and largely statistical, and we have to apply that to specific decisions about an individual patient. This means we have to make the best recommendations we can with the information we have, be honest about our level of uncertainty, and convey the range of possible outcomes based on various decisions.

As a physician you have to develop a certain comfort level with uncertainty. The simple fact is – we don’t know everything. The human body is extremely complex, and there are over 7 billion people on the planet representing a great deal of variation. Our data is incomplete and largely statistical, and we have to apply that to specific decisions about an individual patient. This means we have to make the best recommendations we can with the information we have, be honest about our level of uncertainty, and convey the range of possible outcomes based on various decisions. Researchers at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering have

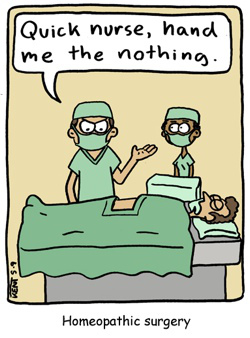

Researchers at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering have  These are always amusing, but I do admit to a little bit of guilt. My concern is that the individuals involved may be diagnosable, and is it really fair to publicly criticize their “work.” But then I realize I cannot diagnose people from afar, and they placed their work in the public arena, so it’s fair game.

These are always amusing, but I do admit to a little bit of guilt. My concern is that the individuals involved may be diagnosable, and is it really fair to publicly criticize their “work.” But then I realize I cannot diagnose people from afar, and they placed their work in the public arena, so it’s fair game.