May 16 2024

Grief Tech

In the awesome show, Black Mirror, one episode features a young woman who lost her husband. In her grief she turns to a company that promises to give her at least a partial experience of her husband. They sift through every picture, video, comment, and other online trace of the person and construct from that a virtual avatar. At first the avatar just texts with the wife, which then progresses to phone calls, and then finally to a full robotic avatar indistinguishable from the lost husband. Except – it is not really indistinguishable. It’s a compliant AI that isn’t quite human.

In the awesome show, Black Mirror, one episode features a young woman who lost her husband. In her grief she turns to a company that promises to give her at least a partial experience of her husband. They sift through every picture, video, comment, and other online trace of the person and construct from that a virtual avatar. At first the avatar just texts with the wife, which then progresses to phone calls, and then finally to a full robotic avatar indistinguishable from the lost husband. Except – it is not really indistinguishable. It’s a compliant AI that isn’t quite human.

So-called grief tech is possible now and is getting more popular. This is another instance of technology creating a new ethical situation that we have to confront, and it is too early to really tell what the impact will be. There are companies, mostly in Asia, that will create the virtual avatar of a dead loved-one for you (one company charges $50,000 for the service). They don’t just scrub the internet, they will make hours of high definition video and interviews to create the raw material to train the AI. The result is a high fidelity visual avatar speaking in the voice of the deceased with a chat-bot mimicking their style with access to lots of information about their life.

The important question is not, how good is it. It’s already very good, and clearly it will get incrementally better. It will also likely get much cheaper. Eventually it will be an app on your phone. The question is – is all this a net positive and healthy experience or is it mostly creepy and unhealthy? I suspect the answer will likely be yes – both. It will depend on the individual and the situation, and even for the individual there are likely to be positive and negative aspects. Either way – we are about to find out.

The primary concern is that having a chatbot of a lost loved-one may delay acceptance and the ability to move on. The creepy factor comes from two sources, I think. One is the uncanny valley of not being able to quite accurately duplicate the person. One company claims 96.5% fidelity (that’s oddly specific), but that is right in the uncanny valley. The other is the knowledge that the AI is not your loved-one. Like in the Black Mirror episode, it will look and talk like them, but it’s not them, and you will be reminded of that in thousands of subtle ways. What will be the emotional impact of that?

On the pro side, the ability to interact with a virtual loved-one can potentially be part of the healing process. It may allow people to process their grief, to work out unresolved conflict or pain, and to ease into their loss. As the BBC reports, James, who made such a chat bot out of his father, report:

“It’s not him retreating into this very fuzzy memory. I have this wonderful interactive compendium I can turn to.”

In this sense it’s just the next iteration of a memento. In the past people had portraits and letters from their deceased loved-ones. Then photography allowed for accurate pictures as keepsakes. Then we entered the world of video, which has become increasingly high quality and ubiquitous. Now we can take high quality video on demand right from our phone. I don’t think anyone would consider it unhealthy or creepy to watch video of a dead relative in order to fuel our memories of them. James sees this as just the next step – that video is now interactive, and can tell stories in his father’s voice about his father’s life.

If I had to guess, I think James’s attitude is likely to prevail. We typically are fearful of new technology, and tend to worry about how it will change our lives. But then the new tech simply becomes accepted, and we realize we worried for nothing. Fretting about the impact of chatbots of deceased loved-ones may seem as quaint in a generation as worrying about the psychological trauma of watching talking video of the deceased.

You still know your loved-one is gone. The AI is not your loved-one. You will still miss them and feel grief and loss. But you may have a really good memento of them to help remember them – what they looked like, sounded like, and moments from your life together.

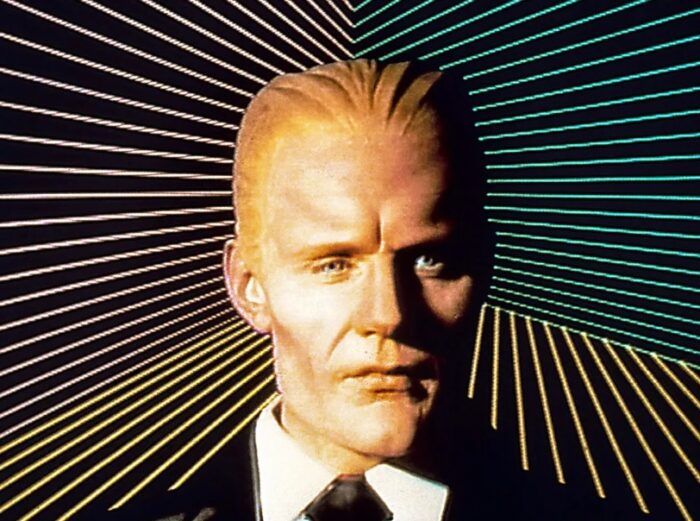

Such tech also raises other questions. Is it OK to create a chatbot avatar of a deceased celebrity? Who gets to decide? Who gets to use the chatbot, and for what purposes? What if we make a Max Headroom version, clearly an AI but also clearly representing the person?

Farther in the future we may have to confront other technology pushing the limits even more. What happens when we have truly sentient AI? Could we train a sentient AI on the collected works, video, and audio of Carl Sagan to make not just a Sagan Chatbot, but a Sagan AI that is fully sentient? Should we? To avoid copyright issues, perhaps someone will make a Sagan-like AI, clearly a knockoff of Sagan, but not him specifically. Would that be ethical to do to the AI, or do we need to let them develop naturally into their own persona?

The only thing that’s clear is that technology will continue to challenge our ethics and society.