Aug 23 2022

Do We Need a New Theory of Decision Making?

How people make decisions has been an intense area of study from multiple angles, including various disciplines within psychology and economics. Here is a fascinating article that provides some insight into the state of the science addressing this broad question. It is framed as a meta-question – do we have the right underlying model that properly ties together all the various aspects of human decision-making? It is not a systematic review of this question, and really just addresses one key concept, but I think it helps frame the question.

How people make decisions has been an intense area of study from multiple angles, including various disciplines within psychology and economics. Here is a fascinating article that provides some insight into the state of the science addressing this broad question. It is framed as a meta-question – do we have the right underlying model that properly ties together all the various aspects of human decision-making? It is not a systematic review of this question, and really just addresses one key concept, but I think it helps frame the question.

The title reflects the author’s (Jason Collins) approach – “We don’t have a hundred biases, we have the wrong model.” The article is worth a careful read or two if you are interested in this topic, but here’s my attempt at a summary with some added thoughts. As with many scientific phenomena, we can divide the approach to human decision making into at least two levels, describing what people do and an underlying theory (or model) as to why they behave that way. Collins is coming at this mostly from a behavioral economics point of view, which starts with the “rational actor” model, the notion that people generally make rational decisions in their own self-interest. This model also includes the premise the individual have the computational mental power to arrive at the optimal decision, and the willpower to carry it out. When research shows that people deviate from a pure rational actor model of behavior, those deviations are deemed “biases”. I’ve discussed many such biases in this blog, and hundreds have been identified – risk aversion, sunk cost, omission bias, left-most digit bias, and others. It’s also recognized that people do not have unlimited computational power or willpower.

Collins likens this situation to the Earth-centric model of the universe. Geocentrism was an underlying model of how the universe worked, but did not match observations of the actual universe. So astronomers introduced more and more tweaks and complexities to explain these deviations. Perhaps, Collins argues, we are still in the “geocentrism” era of behavioral psychology and we need a new underlying model that is more elegant, accurate, and has more predictive power – a heliocentrism for human decision-making. He acknowledges that human behavior it too complex and multifaceted to follow a model as simple and elegant as, say, Kepler’s laws of planetary motion, but perhaps we can do better than the rational actor model tweaked with many biases to explain each deviation.

Deviations from the rational actor model are also explained by the addition of further parallel models, that are either situational or account for other factors, such as emotions. But Collins doesn’t like this approach either:

But that proliferation of models is a problem parallel to the accumulation of biases. A proliferation of models with slight tweaks to the rational-actor model shows the flexibility and power of that model, but also its major flaw. Economics journals are full of models of decision-making designed to capture a particular phenomenon. But rarely are these models systematically tested, rejected or improved, or ultimately integrated into a common theoretical framework. And if you can find a model to explain everything, again, you explain nothing.

I get what he is saying, but I’m not sure he has convinced me here. As an approach to research, I agree with him – we have to question our underlying approach, and search for ever-more fundamental models or understandings of whatever phenomenon we are researching. I often bring this up myself when commenting on new neuroscience research – are we at the bedrock level, or still looking at downstream effects?

But what if we essentially are at or near the bedrock level with behavioral psychology research? I don’t mean that we have discovered everything, I mean there may not be an elegant underlying theory that we are missing. Or looked at a different way, perhaps the new model that Collins is looking for is that there is no new model. I personally have always made sense of the behavioral neuroscience research by thinking of human decision-making as a noisy committee. There are many factors simultaneously at work, pushing in different directions, and in the end one cluster of voices is simply louder than the others. Our model is messy because reality is messy – human decision-making is a magnificent kluge. I guess that is a model unto itself, but it may be the simplest explanation of what is going on.

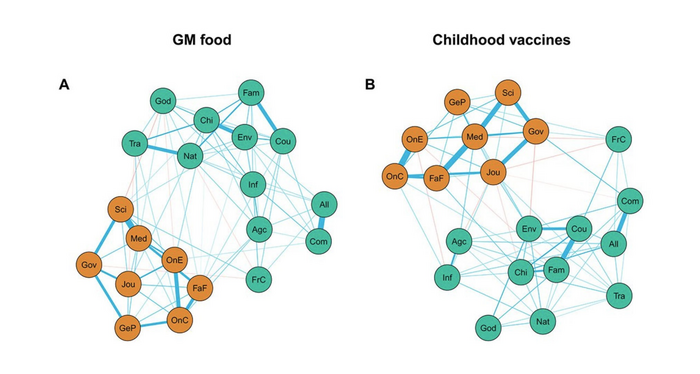

If the kluge model is accurate, then the best we can do is come up with a bunch of partial and imperfect models and then tweak the hell out of them with biases and heuristics – basically what we have now. We may be able to add a level of modeling by not only trying to identify each individual “committee” member (to stick with my analogy) but also to describe how they interact. Here is a newly published example: Using a cognitive network model of moral and social beliefs to explain belief change. The research tries to model the degree of cognitive dissonance (the negative feeling that results from simultaneously holding contradictory beliefs) and how this affects changing one’s beliefs when confronted with new information.

The researchers looked at attitudes toward GMO foods and vaccines. They found that those individuals with greater levels of cognitive dissonance (because their set of beliefs were in more internal conflict) were more likely to change their beliefs when confronted with new information, than those with lower levels of cognitive dissonance. For example, dissonance may result if a person believes that scientists are generally trustworthy, but they don’t trust them about vaccines. This makes sense from a cognitive dissonance model – people with low levels of dissonance have already found a region of stability and are less likely to be pushed from that cognitive location. Those with higher levels of dissonance are less stable, and therefore more likely to change. But interestingly, the new model could not predict whether the subjects with high levels of dissonance would change their beliefs in line with the new information, or entrench their previous beliefs.

One way to make sense of these results is that confronting people with high levels of cognitive dissonance with new information that highlights or exacerbates this dissonance were motivated to make a change to lessen that dissonance. However, there are multiple ways to do this. You can align your beliefs more with reality, or you can rationalize your existing beliefs, which further entrenches them. Both work from a cognitive dissonance model.

But again this is only a partial explanation for human behavior, as we simultaneously operate under different cognitive paradigms and motivations. The response to cognitive dissonance may therefore be modified by baseline level of scientific knowledge, social pressure from one’s in-group, how much processing work would be required to make different changes and how cognitively fatigued that person may have been at that time, and countless other factors.

These deviations, biases, tweaks, and heuristics may not be flaws in the model, therefore, but real effects caused by actual networks in the brain. Collins does acknowledge that we may look to computer science and evolutionary psychology to help us build better decision-making models. How AI algorithms learn to optimize outcomes may provide analogies for how human brains optimize behavioral outcomes.

I will add something which I think is an oversight in Collins’ article – how about neuroscience? Identifying specific functional circuits in the brain, what they do, and how they interact with other functional circuits is, I think, as close to bedrock as we will ever get when it comes to human behavior. I don’t know if this is a bias among behavioral scientists, but it does mirror a recent conversation I had with Richard Wiseman (a behavioral social psychologist). He is specifically uninterested in the circuits that underlie human behavior, because he thinks of it as something we cannot change. But I think he and Collins are both missing the same point – behavior is what the brain does, and if we want to truly understand behavior at the bedrock level we have to understand how the brain works. These disciplines are related, not separate.

If a more elegant model of human behavior is possible, than integrating all these various disciplines may be our only hope.