Oct 31 2017

Conspiracy Thinking and Epistemology

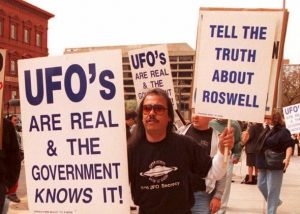

Just last week I discussed a study looking at the correlation between belief in conspiracy theories and hyperactive pattern recognition. The quick version is this – belief in false patterns (such as bizarre conspiracy theories) results from a tendency to detect false patterns and a lack of filtering out those detections. The question for psychologists is, how much of an increased tendency to believe grand conspiracies is due to increased pattern recognition and how much is due to impaired reality testing? My assumption would be that both are involved to varying degrees in different people. The study found that there is a correlation between conspiracy beliefs and pattern recognition – which supports that hypothesis, but does not refute the role of decreased reality testing or other variables, such as culture, ideology, and self-esteem.

Just last week I discussed a study looking at the correlation between belief in conspiracy theories and hyperactive pattern recognition. The quick version is this – belief in false patterns (such as bizarre conspiracy theories) results from a tendency to detect false patterns and a lack of filtering out those detections. The question for psychologists is, how much of an increased tendency to believe grand conspiracies is due to increased pattern recognition and how much is due to impaired reality testing? My assumption would be that both are involved to varying degrees in different people. The study found that there is a correlation between conspiracy beliefs and pattern recognition – which supports that hypothesis, but does not refute the role of decreased reality testing or other variables, such as culture, ideology, and self-esteem.

This week I am going to discuss another recent study looking at belief in conspiracies and their correlation with beliefs about the nature of knowledge (epistemic beliefs). These researchers are focusing on the other end of the equation – the methods we use to assess knowledge and form beliefs, rather than the more basic function of perceiving patterns. They start with a helpful review of previous literature:

There is also some evidence that individuals’ styles of thinking can influence their willingness to accept claims lacking empirical evidence. Individuals who tend to see intentional agency behind every event are more likely to believe conspiracy theories, as are those who attribute extraordinary events to unseen forces or interpret events through the Manichean narrative of good versus evil. Those who mistrust authority, who are convinced that nothing is as it seems, and who lack control over their environment are also more predisposed to conspiracist ideation.

Taken together you may look at these cognitive traits as a strategy or narrative for understanding the world, which can often be complex and overwhelming. There is an underlying assumption that dark forces are controlling events for their own nefarious purposes. Once that assumption is in place it can be a powerful lens through which everything is perceived, one that prevents its own refutation. The conspiracy lens twists logic back in on itself, forming a self-contained belief system immune to external validation or refutation.

For the current study the authors focus on epistemic beliefs – notions about the nature of knowledge itself. I found their results entirely unsurprising, as they are consistent with prior research into conspiracy thinking. The first factor they looked at was faith in intuition or facts. Do you trust your gut feelings about a subject, or would you set aside those feelings if the empirical evidence told a different story? Second they looked at the extent to which subjects believe facts are political vs objective.

They asked subjects to rank twelve statements on a scale of 1-5, four each probing their beliefs about the reliability of intuition, the need for evidence, and the political nature of facts. They also had them rank seven different conspiracy theories from 1 (definitely not true) to 9 (definitely true) and considered a rank of 6 or higher as belief in the conspiracy. On their list belief in a JFK assassination conspiracy ranked the highest, at 45.7% belief. The Apollo moon landing hoax was at the bottom at 15.3%. I was a bit surprised that almost a third, 30.7%, believe that a New World Order seeks to replace sovereign governments and rule the world.

As you can see in these scatter plots, belief in intuition, lack of need for evidence, and belief that facts are political all correlate with increased belief in conspiracy theories. There is also a tremendous amount of individual variability within these general trends.

For comparison they also correlated epistemic beliefs and misperceptions about political issues that are not specifically related to conspiracy theories. Specifically they look at belief in global warming, that vaccines cause autism, that Iraq had WMD prior to the war, and that Muslims are inherently violent. They also found a strong correlation, similar but not as strong as with conspiracy theories.

This is also not surprising, in part because these political beliefs incorporate conspiracy theories as well. The separation is not clean. Those who reject the scientific consensus on global warming justify that rejection by claiming there is a conspiracy of scientists and politicians to hoax the world for their own purposes. Antivaxers believe the medical profession and Big Pharma are conspiring to sell harmful vaccines.

The authors conclude:

We find that individuals who trust their intuition, putting more faith in their ability to use intuition to assess factual claims than in their conscious reasoning skills, are uniquely likely to exhibit conspiracist ideation. Those who maintain that beliefs must be in accord with available evidence, in contrast, are less likely to embrace conspiracy theories, and they are less likely to endorse other falsehoods, even on politically charged topics. Finally, those who view facts as inexorably shaped by politics and power are more prone to misperception than those who believe that truth transcends social context. These individual-difference measures are fairly stable over time. Although the influence of epistemic beliefs is sometimes conditioned on ideology, this is the exception; in most instances the two types of factors operate independent of one another.

What I like about this study is that it focuses on factors that may be more amenable to education, rather than being deeply ingrained personality traits. Once again, education in science and critical thinking can give people the “conscious reasoning skills” to assess their own beliefs more thoroughly and critically.