Jan 14 2021

Commercializing Low Earth Orbit

For the SGU podcast this week we interviewed Phil McAlister, who is the Director of Commercial Spaceflight Development at NASA Headquarters (this will be available starting 1/16). It’s an excellent interview I recommend listening to – the overall theme of the discussion is that NASA is pulling back from low Earth orbit (LEO) so that they can focus on deep space exploration, including cis-Lunar space and eventually Mars.

For the SGU podcast this week we interviewed Phil McAlister, who is the Director of Commercial Spaceflight Development at NASA Headquarters (this will be available starting 1/16). It’s an excellent interview I recommend listening to – the overall theme of the discussion is that NASA is pulling back from low Earth orbit (LEO) so that they can focus on deep space exploration, including cis-Lunar space and eventually Mars.

There are a few facets of this decision by NASA, including the shift if focus. The second is that NASA has already paved the way for the private sector, developing the technology and experience to occupy and work in LEO. So in a way they feel they have accomplished their mission and feel it’s time to move on. Further, the private sector is likely to have new and fresh ideas, and to focus much more of efficiency and cost-effectiveness than NASA. And finally, it may ultimately be cheaper for NASA to simply outsource LEO to the private sector rather than do everything themselves.

The upshot of all this is that it has worked out quite well, in all of these aspects. SpaceX is the most dramatic example. They have pioneered new reusable rocket technology. They are now the first private company approved by NASA to launch humans into space, and they can do it more cheapy than NASA, or by purchases seats from Russia. Further, Boeing will likely be approved for human launch soon, and then for the first time in history the US will have redundant capability to launch humans to space.

The next phase of ceding LEO to the private sector is the International Space Station (ISS). The station will remain operational until at least 2028, and perhaps extended a few years beyond that. But then, the ISS will be decommissioned and will be deorbited. An amazing era of spaceflight will come to an end. NASA has no plans to replace the ISS. Rather, they plan to allow the private sector to take over the LEO space station space.

In 2024 (or thereabouts) a private company called Axiom is planning on attaching new modules to the ISS, including a crew module, a work module, and an observation deck. Sometime before the ISS is decommissioned they will break away from the station and become a “free-flying” station on their own, and will expand from their. That will require adding capabilities to become self-sufficient without the primary station.

The hope is that other companies will also build LEO stations. One likely way to finance all this is through space tourism. Obviously, like most industries, this will be available at first only to the superrich, but if Musk and others have their way the cost of getting into LEO should drop precipitously. I don’t envision this being cheap for the foreseeable future, but it may come down to the point where the merely well-off can afford it.

In addition, research and manufacturing may have a niche in LEO and help finance operations there. NASA is still likely to require LEO services, as the first leg of their deep space operations, if nothing else, and so they will remain an important customer as well. Space programs in other countries, of course, will too. In fact we may end up with an LEO infrastructure mostly by private companies providing services for the world’s space programs. This may also lower the bar for economically smaller countries to get involved.

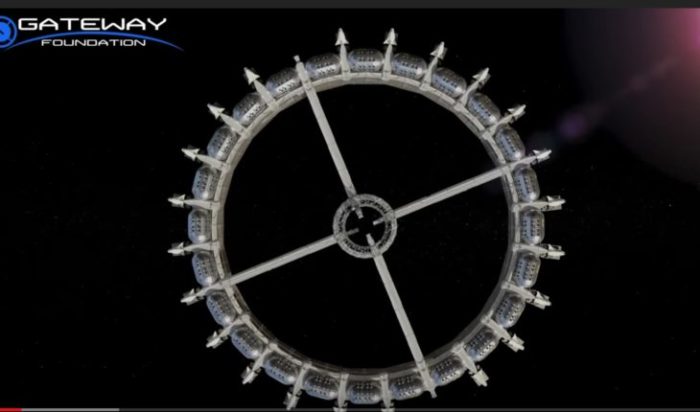

One thing we did not talk about on the interview was the Gateway Project. This is another private foundation with the goal of creating the first space station with artificial gravity from rotation. Their design, called the Voyager Station concept, looks similar to the ring station from the film 2001. One important difference is that the ring is not one continuous space, but a series of individual modules (which makes more sense from a safety and structural integrity perspective. This seems like the inevitable direction for space stations.

Microgravity is great for research that requires it, and may also be exploited for manufacturing, but it wreaks havoc on the human body. The idea, however, is to have a microgravity station attached to a rotating station so that workers in space can do their microgravity work during the day, then go to the rotating segment for the rest of their activities, including exercise and sleeping. This lifestyle still needs to be studied, but it is likely to mitigate most if not all of the negative effects of long-term microgravity.

One possible design is to have concentric rings of difference sizes, and therefore different gravities. You could have a Moon ring surrounded by a Mars ring and then an Earth ring, all simulating the gravity of these worlds.

The company is also developing the technology to have automated robotic construction in LEO. Orbital construction is another aspect of the LEO infrastructure that will help make activities there self-sustaining.

Yet another important aspect of the infrastructure necessary to maintain a presence in space is astronauts – people with experience living and working in space. These various projects will require hundreds of space workers, and they may provide an important resource for NASA and others who will need experienced astronauts.

This all sounds good, and there does seem to be a coherent plan for how to expand human operations in LEO. I think the mix and collaboration between the public and private sector is also a good idea and seems to be working very well. There are a couple of unknowns, however, that could make or break these plans.

One is safety. While NASA has extreme quality control, astronauts know they are essentially test pilots and that the risks are high. We have lost astronauts, on the ground and in space, and we took it on the chin and moved forward. How the private sector responds when the inevitable accident and death occurs remains to be seen.

The second variable, which may be related to the fist, is profitability. Expanding the private-sector LEO infrastructure assumes that at some point this activity will be profitable. Space tourism sounds great, but how many people would be willing to spend how much to experience LEO? We’ll see. Will any manufacturing application be cost effective in microgravity? Will asteroid mining support all this? It’s likely to be massively profitable, but how much of those profits will support LEO space stations? No one knows the answer to these questions.

If it turns out that the private space industry requires decades, perhaps a century or more, of subsidies before it is truly net profitable, will the public sector be willing to provide those subsidies, how much, and for how long? This may come in the form of simply purchasing their services, but still that requires a public sector commitment to space travel.

I hope this all does work out, and I predict that it will. But I also don’t think it will just happen automatically. It will require commitment, and a dedication to a vision of humanity as a species that lives beyond the limits of Earth’s surface. The long term advantages are worth it, but we may have to sacrifice short term investments to get there. I do think, overall, the NASA approach is a good one. Their decision to cede LEO to the private sector was smart, and so far it is worked out.