Mar 04 2024

Climate Sensitivity and Confirmation Bias

I love to follow kerfuffles between different experts and deep thinkers. It’s great for revealing the subtleties of logic, science, and evidence. Recently there has been an interesting online exchange between a physicists science communicator (Sabine Hossenfelder) and some climate scientists (Zeke Hausfather and Andrew Dessler). The dispute is over equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) and the recent “hot model problem”.

I love to follow kerfuffles between different experts and deep thinkers. It’s great for revealing the subtleties of logic, science, and evidence. Recently there has been an interesting online exchange between a physicists science communicator (Sabine Hossenfelder) and some climate scientists (Zeke Hausfather and Andrew Dessler). The dispute is over equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) and the recent “hot model problem”.

First let me review the relevant background. ECS is a measure of how much climate warming will occur as CO2 concentration in the atmosphere increases, specifically the temperature rise in degrees Celsius with a doubling of CO2 (from pre-industrial levels). This number of of keen significance to the climate change problem, as it essentially tells us how much and how fast the climate will warm as we continue to pump CO2 into the atmosphere. There are other variables as well, such as other greenhouse gases and multiple feedback mechanisms, making climate models very complex, but the ECS is certainly a very important variable in these models.

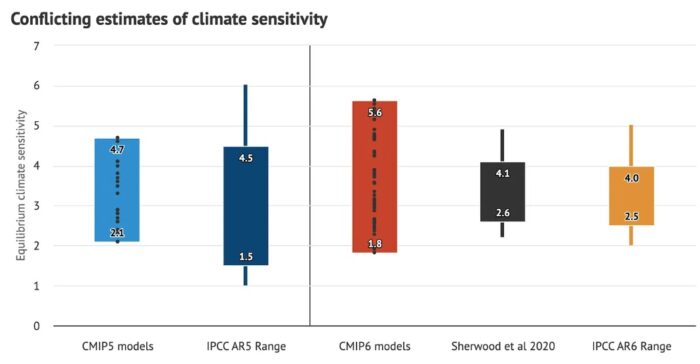

There are multiple lines of evidence for deriving ECS, such as modeling the climate with all variables and seeing what the ECS would have to be in order for the model to match reality – the actual warming we have been experiencing. Therefore our estimate of ECS depends heavily on how good our climate models are. Climate scientists use a statistical method to determine the likely range of climate sensitivity. They take all the studies estimating ECS, creating a range of results, and then determine the 90% confidence range – it is 90% likely, given all the results, that ECS is between 2-5 C.

Hossenfelder did a recent video discussing the hot model problem. This refers to the fact that some of the recent climate models, ones that are ostensible improved from older models incorporating better physics and cloud modeling, produced an estimate for ECS outside the 90% confidence interval, with ECSs above 5.0. Hossenfelder expressed grave concern that if these models are closer to the truth on ECS we are in big trouble. There is likely to be more warming sooner, which means we have even less time than we thought to decarbonize our economy if we want to avoid the worst climate change has in store for us. Some climate scientists responded to her video, and then Hossenfelder responded back (links above). This is where it gets interesting.

To frame my take on this debate a bit, when thinking about any scientific debate we often have to consider two broad levels of issues. One type of issue is generic principles of logic and proper scientific procedure. These generic principles can apply to any scientific field – P-hacking is P-hacking, whether you are a geologist or chiropractor. This is the realm I generally deal with, basic principles of statistics, methodological rigor, and avoiding common pitfalls in how to gather and interpret evidence.

The second relevant level, however, is topic-specific expertise. Here I do my best to understand the relevant science, defer to experts, and essentially try to understand the consensus of expert opinion as best I can. There is often a complex interaction between these two levels. But if researchers are making egregious mistakes on the level of basic logic and statistics, the topic-specific details do not matter very much to that fact.

What I have tried to do over my science communication career is to derive a deep understanding of the logic and methods of good science vs bad science from my own field of expertise, medicine. This allows me to better apply those general principles to other areas. At the same time I have tried to develop expertise in the philosophy of science, and understanding the difference between science and pseudoscience.

In her response video Hossenfelder is partly trying to do the same thing, take generic lessons from her field and apply them to climate science (while acknowledging that she is not a climate scientist). Her main point is that, in the past, physicists had grossly underestimated the uncertainty of certain measurements they were making (such as the half life of protons outside a nucleus). The true value ended up being outside the earlier uncertainty range – h0w did that happen? Her conclusions was that it was likely confirmation bias – once a value was determined (even if just preliminary) then confirmation bias kicks in. You tend to accept later evidence that supports the earlier preliminary evidence while investigating more robustly any results that are outside this range.

Here is what makes confirmation bias so tricky and often hard to detect. The logic and methods used to question unwanted or unexpected results may be legitimate. But there is often some subjective judgement involved in which methods are best or most appropriate and there can be a bias in how they are applied. It’s like P-hacking – the statistical methods used may be individually reasonable, but if you are using them after looking at data their application will be biased. Hossenfelder correctly, in my opinion, recommends deciding on all research methods before looking at any data. The same recommendation now exists in medicine, even with pre-registration of methods before collective data and reviewers now looking at how well this process was complied with.

So Hausfather and Dessler make valid points in their response to Hossenfelder, but interestingly this does not negate her point. Their points can be legitimate in and of themselves, but biased in their application. The climate scientists point out (as others have) that the newer hot models do a relatively poor job of predicting historic temperatures and also do a poor job of modeling the most recent glacial maximum. That sounds like a valid point. Some climate scientists have therefore recommended that when all the climate models are averaged together to produce a probability curve of ECS that models which are better and predicting historic temperatures be weighted heavier than models that do a poor job. Again, sounds reasonable.

But – this does not negate Hossenfelder’s point. They decided to weight climate models after some of the recent models were creating a problem by running hot. They were “fixing” the “problem” of hot models. Would they have decided to weight models if there weren’t a problem with hot models? Is this just confirmation bias?

None of this means that there fix is wrong, or that the hot models are right. But what it means is that climate scientists should acknowledge exactly what they are doing. This opens the door to controlling for any potential confirmation bias. The way this works (again, generic scientific principle that could apply to any field) is to look a fresh data. Climate scientists need to agree on a consensus method – which models to look at, how to weight their results – and then do a fresh analysis including new data. Any time you make any change to your methods after looking at the data, you cannot really depend on the results. At best you have created a hypothesis – maybe this new method will give more accurate results – but then you have to confirm that method by applying it to fresh data.

Perhaps climate scientists are doing this (I suspect they will eventually), although Hausfather and Dessler did not explicitly address this in their response.

It’s all a great conversation to have. Every scientific field, no matter how legitimate, could benefit from this kind of scrutiny and questioning. Science is hard, and there are many ways bias can slip in. It’s good for scientists in every field to have a deep and subtle understanding of statistical pitfalls, how to minimize confirmation bias and p-hacking, and the nature of pseudoscience.