Nov

17

2025

I am currently in Dubai at the Future Forum conference, and later today I am on a panel about the future of the mind with two other neuroscientists. I expect the conversation to be dynamic, but here is the core of what I want to say.

I am currently in Dubai at the Future Forum conference, and later today I am on a panel about the future of the mind with two other neuroscientists. I expect the conversation to be dynamic, but here is the core of what I want to say.

As I have been covering here over the years in bits and pieces, there seems to be several technologies converging on at least one critical component of research into consciousness and sentience. The first is the ability to image the functioning of the brain, in addition to the anatomy, in real time. We have functional MRI scanning, PET, and EEG mapping which enable us to see cerebral blood flow, metabolism and electrical activity. This allows researchers to ask questions such as: what parts of the brain light up when a subject is experiencing something or performing a specific task. The data is relatively low resolution (compared to the neuronal level of activity) and noisy, but we can pull meaningful patterns from this data to build our models of how the brain works.

The second technology which is having a significant impact on neuroscience research is computer technology, including but not limited to AI. All the technologies I listed above are dependent on computing, and as the software improves, so does the resulting imaging. AI is now also helping us make sense of the noisy data. But the computing technology flows in the other direction as well – we can use our knowledge of the brain to help us design computer circuits, whether in neural networks or even just virtually in software. This creates a feedback loop whereby we use computers to understand the brain, and the resulting neuroscience to build better computers.

Continue Reading »

Oct

06

2025

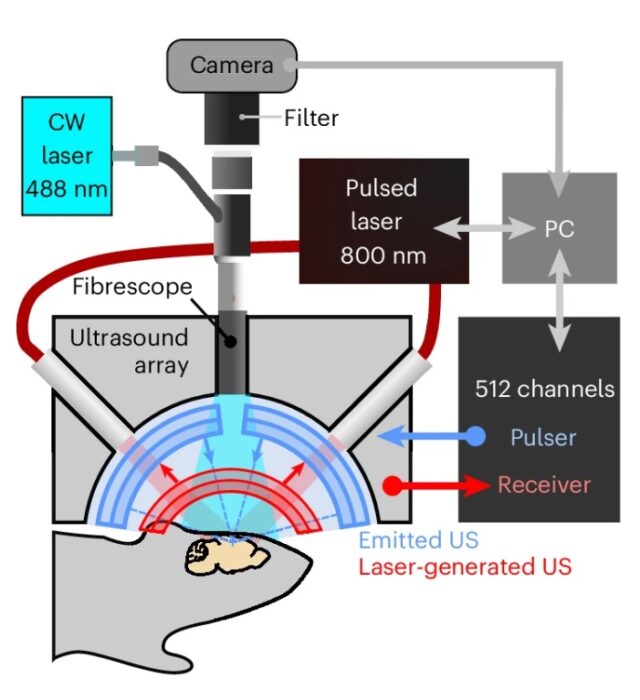

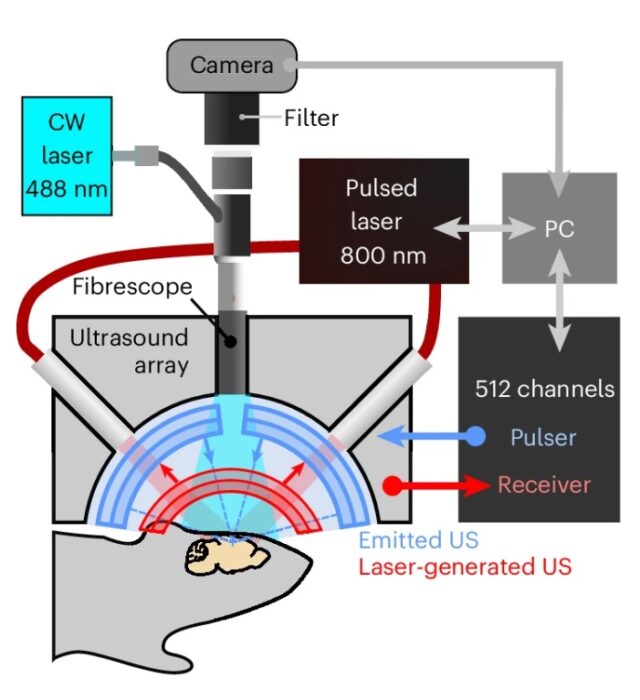

The technique is called holographic transcranial ultrasound neuromodulation – which sounds like a mouthful but just means using multiple sound waves in the ultrasonic frequency to affect brain function. Most people know about ultrasound as an imaging technique, used, for example, to image fetuses while still in the womb. But ultrasound has other applications as well.

The technique is called holographic transcranial ultrasound neuromodulation – which sounds like a mouthful but just means using multiple sound waves in the ultrasonic frequency to affect brain function. Most people know about ultrasound as an imaging technique, used, for example, to image fetuses while still in the womb. But ultrasound has other applications as well.

Sound wave are just another form of directed energy, and that energy can be used not only to image things but to affect them. In higher intensity they can heat tissue and break up objects through vibration. Ultrasound has been approved to treat tumor by heating and killing them, or to break up kidney stones. Ultrasound can also affect brain function, but this has proven very challenging.

The problem with ultrasonic neuromodulation is that low intensity waves have no effect, while high intensity waves cause tissue damage through heating. There does not appear to be a window where brain function can be safely modulated. However, a new study may change that.

The researchers are developing what they call holographic ultrasound neuromodulation – they use many simultaneous ultrasound origin points that cause areas of constructive and destructive interference in the brain, which means there will be locations where the intensity of the ultrasound will be much higher. The goal is to activate or inhibit many different points in a brain network simultaneously. By doing this they hope to affect the activity of the network as a whole at low enough intensity to be safe for the brain.

Continue Reading »

Sep

29

2025

We are all familiar with the notion of “being on autopilot” – the tendency to initiate and even execute behaviors out of pure habit rather than conscious decision-making. When I shower in the morning I go through roughly the identical sequence of behaviors, while my mind is mostly elsewhere. If I am driving to a familiar location the word “autopilot” seems especially apt, as I can execute the drive with little thought. Of course, sometimes this leads me to taking my most common route by habit even when I intend to go somewhere else. You can, of course, override the habit through conscious effort.

We are all familiar with the notion of “being on autopilot” – the tendency to initiate and even execute behaviors out of pure habit rather than conscious decision-making. When I shower in the morning I go through roughly the identical sequence of behaviors, while my mind is mostly elsewhere. If I am driving to a familiar location the word “autopilot” seems especially apt, as I can execute the drive with little thought. Of course, sometimes this leads me to taking my most common route by habit even when I intend to go somewhere else. You can, of course, override the habit through conscious effort.

That last word – effort – is likely key. Psychologists have found that humans have a tendency to maximize efficiency, which is another way of saying that we prioritize laziness. Being lazy sounds like a vice, but evolutionarily it probably is about not wasting energy. Animals, for example, tend to be active only as much as is absolutely necessary for survival, but we tend to see their laziness as conserving precious energy.

We developed for conservation of mental energy as well. We are not using all of our conscious thought and attention to do everyday activities, like walking. Some activities (breathing-walking) are so critical that there are specialized circuits in the brain for executing them. Other activities are voluntary or situation, like shooting baskets, but may still be important to us, so there is a neurological mechanism for learning these behaviors. The more we do them, the more subconscious and automatic they become. Sometimes we call this “muscle memory” but it’s really mostly in the brain, particularly the cerebellum. This is critical for mental efficiency. It also allows us to do one common task that we have “automated” while using our conscious brain power to do something else more important.

Continue Reading »

Sep

04

2025

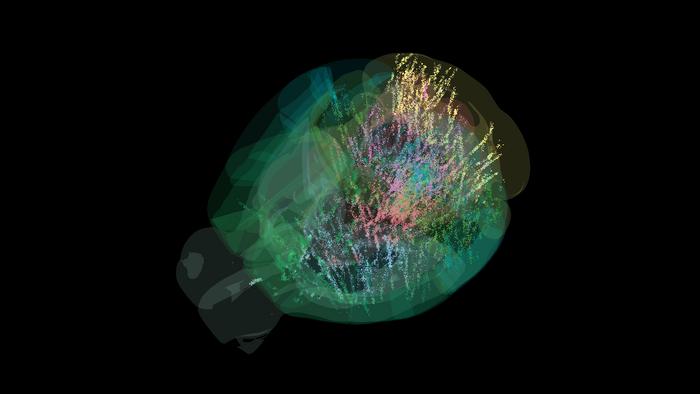

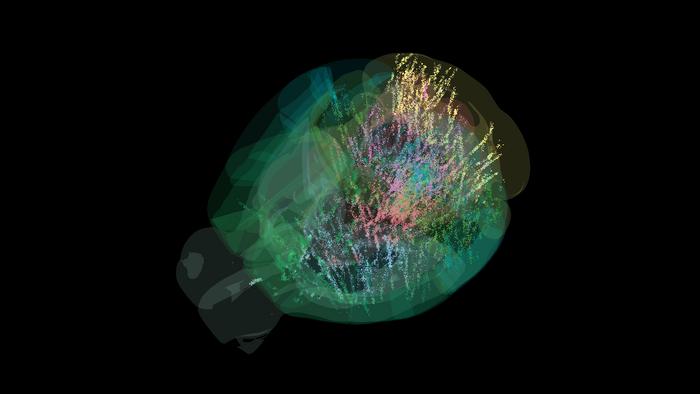

Researchers have just presented the results of a collaboration among 22 neuroscience labs mapping the activity of the mouse brain down to the individual cell. The goal was to see brain activity during decision-making. Here is a summary of their findings:

Researchers have just presented the results of a collaboration among 22 neuroscience labs mapping the activity of the mouse brain down to the individual cell. The goal was to see brain activity during decision-making. Here is a summary of their findings:

“Representations of visual stimuli transiently appeared in classical visual areas after stimulus onset and then spread to ramp-like activity in a collection of midbrain and hindbrain regions that also encoded choices. Neural responses correlated with impending motor action almost everywhere in the brain. Responses to reward delivery and consumption were also widespread. This publicly available dataset represents a resource for understanding how computations distributed across and within brain areas drive behaviour.”

Essentially, activity in the brain correlating with a specific decision-making task was more widely distributed in the mouse brain than they had previously suspected. But more specifically, the key question is – how does such widely distributed brain activity lead to coherent behavior. The entire set of data is now publicly available, so other researchers can access it to ask further research questions. Here is the specific behavior they studied:

“Mice sat in front of a screen that intermittently displayed a black-and-white striped circle for a brief amount of time on either the left or right side. A mouse could earn a sip of sugar water if they quickly moved the circle toward the center of the screen by operating a tiny steering wheel in the same direction, often doing so within one second.”

Further, the mice learned the task, and were able to guess which side they needed to steer towards even when the circle was very dim based on their past experience. This enabled the researchers to study anticipation and planning. They were also able to vary specific task details to see how the change affected brain function. Any they recorded the activity of single neurons to see how their activity was predicted by the specific tasks.

Continue Reading »

Aug

12

2025

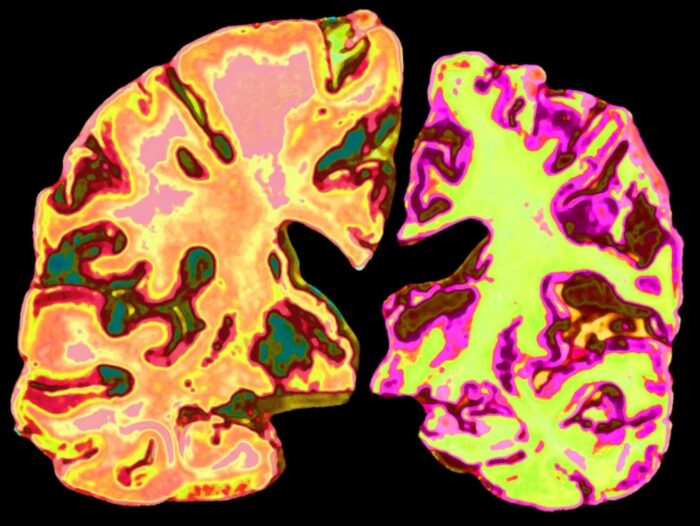

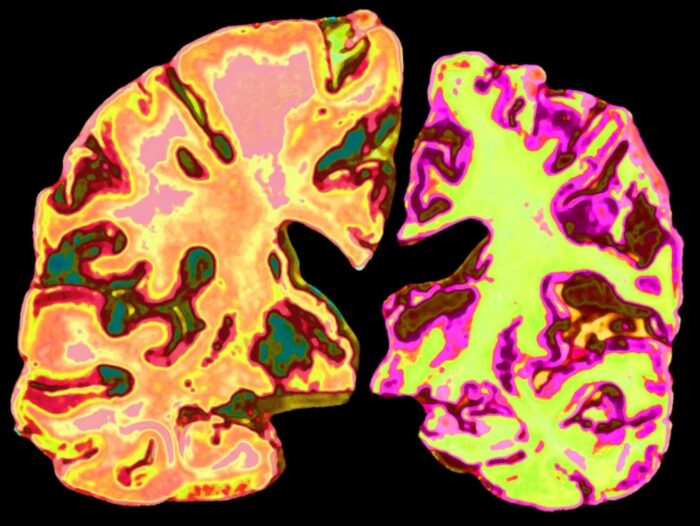

This is an interesting story, and I am trying to moderate my optimism. Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the major cause of dementia in humans, is a very complex disease. We have been studying it for decades, revealing numerous clues as to what kicks it off, what causes it to progress, and how to potentially treat it. This has lead to a lot of knowledge about the disease, but only recently resulted an effective disease-modifying treatments – the anti-amyloid treatments.

This is an interesting story, and I am trying to moderate my optimism. Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the major cause of dementia in humans, is a very complex disease. We have been studying it for decades, revealing numerous clues as to what kicks it off, what causes it to progress, and how to potentially treat it. This has lead to a lot of knowledge about the disease, but only recently resulted an effective disease-modifying treatments – the anti-amyloid treatments.

Another line of investigation has focused on lithium – that’s right, the element, and a major component of EV batteries. Lithium has long been recognized as a treatment for various mood and mental disorders, and was approved in 1970 in the US for the treatment of bipolar disorder. That is what I learned about it in medical school – it was the standard of care for BD but no one really new how it worked. It was the only “drug” that was just an element. It had a certain mystery to it, but it clearly was effective.

Now lithium is emerging as a potential treatment for AD. A recent study of lithium in mice has brought the treatment into the mainstream press, so it’s worth a review. Because of lithium’s benefit for BD it was studied for its effects on the brain. But also, it was observed that patients getting lithium treatment for BD had a lower risk of AD. Other observational data, such as levels of lithium in drinking water, also appeared to have this protective association. This kind of observational data is never definitive, but it was interesting enough to warrant further research.

Continue Reading »

Jun

12

2025

The human brain is extremely good at problem-solving, at least relatively speaking. Cognitive scientists have been exploring how, exactly, people approach and solve problems – what cognitive strategies do we use, and how optimal are they. A recent study extends this research and includes a comparison of human problem-solving to machine learning. Would an AI, which can find an optimal strategy, follow the same path as human solvers?

The study was specifically designed to look at two specific cognitive strategies, hierarchical thinking and counterfactual thinking. In order to do this they needed a problem that was complex enough to force people to use these strategies, but not so complex that it could not be quantified by the researchers. They developed a system by which a ball may take one of four paths, at random, through a maze. The ball is hidden from view to the subject, but there are auditory clues as to the path the ball is taking. The clues are not definitive so the subject has to gather information to build a prediction of the ball’s path.

What the researchers found is that subjects generally started with a hierarchical approach – this means they broke the problem down into simpler parts, such as which way the ball went at each decision point. Hierarchical reasoning is a general cognitive strategy we employ in many contexts. We do this whenever we break a problem down into smaller manageable components. This term more specifically refers to reasoning that starts with the general and then progressively hones in on the more detailed. So far, no surprise – subjects broke the complex problem of calculating the ball’s path into bite-sized pieces.

What happens, however, when their predictions go awry? They thought the ball was taking one path but then a new clue suggests is has been taking another. That is where they switch to counterfactual reasoning. This type of reasoning involves considering the alternative, in this case, what other path might be compatible with the evidence the subject has gathered so far. We engage in counterfactual reasoning whenever we consider other possibilities, which forces us to reinterpret our evidence and make new hypotheses. This is what subjects did, h0wever they did not do it every time. In order to engage in counterfactual reasoning in this task the subjects had to accurately remember the previous clues. If they thought they did have a good memory for prior clues, they shifted to counterfactual reasoning. If they did not trust their memory, then they didn’t.

Continue Reading »

Jun

03

2025

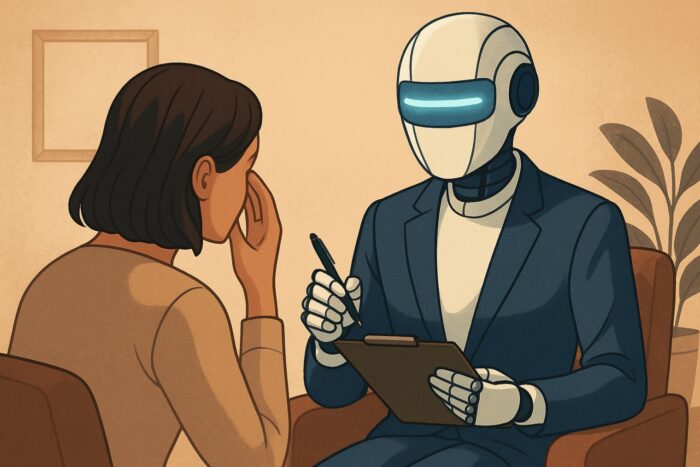

In the movie Blade Runner 2049 (an excellent film I highly recommend), Ryan Gosling’s character, K, has an AI “wife”, Joi, played by Ana de Armas. K is clearly in love with Joi, who is nothing but software and holograms. In one poignant scene, K is viewing a giant ad for AI companions and sees another version of Joi saying a line that his Joi said to him. The look on his face says everything – an unavoidable recognition of something he does not want to confront, that he is just being manipulated by an AI algorithm and an attractive hologram into having feelings for software. K himself is also a replicant, an artificial but fully biological human. Both Blade Runner movies explore what it means to be human and sentient.

In the movie Blade Runner 2049 (an excellent film I highly recommend), Ryan Gosling’s character, K, has an AI “wife”, Joi, played by Ana de Armas. K is clearly in love with Joi, who is nothing but software and holograms. In one poignant scene, K is viewing a giant ad for AI companions and sees another version of Joi saying a line that his Joi said to him. The look on his face says everything – an unavoidable recognition of something he does not want to confront, that he is just being manipulated by an AI algorithm and an attractive hologram into having feelings for software. K himself is also a replicant, an artificial but fully biological human. Both Blade Runner movies explore what it means to be human and sentient.

In the last few years AI (do I still need to routinely note that AI stands for “artificial intelligence”?) applications have seemed to cross a line where they convincingly pass the classic Turing test. AI chatbots are increasingly difficult to distinguish from actual humans. Overall, people are only slightly better than chance at distinguishing human from AI generated text. This is also a moving target, with AIs advancing fairly quickly. So the question is – are we at a point where AI chatbot-based apps are good enough that AIs can serve as therapists? This is a complicated question with a few layers.

The first layer is whether or not people will form a therapeutic relationship with the AI, in essence reacting to them as if they are a human therapist. The point of the Blade Runner reference was just to highlight what I think the clear answer is – yes. Psychologists have long demonstrated that people will form emotional attachments to inanimate objects. We also imbue agency onto anything that acts like an agent, even simple cartoons. We project human emotions and motivations onto animals, especially our pets. People can also form emotional connections to other actual people purely online, even exclusively through text. This is just a fact of neuroscience – our brains do not need a physical biological human in order to form personal attachments. Simply acting or even just looking like an agent is sufficient.

Continue Reading »

Jun

02

2025

I was away on vacation the last week, hence no posts, but am now back to my usual schedule. In fact, I hope to be a little more consistent starting this summer because (if you follow me on the SGU you already know this) I am retiring from my day job at Yale at the end of the month. This will allow me to work full time as a science communicator and skeptic. I have some new projects in the works, and will announce anything here for those who are interested.

I was away on vacation the last week, hence no posts, but am now back to my usual schedule. In fact, I hope to be a little more consistent starting this summer because (if you follow me on the SGU you already know this) I am retiring from my day job at Yale at the end of the month. This will allow me to work full time as a science communicator and skeptic. I have some new projects in the works, and will announce anything here for those who are interested.

On to today’s post – I recently received an e-mail from Janyce Boynton, a former facilitator who now works to expose the pseudoscience of facilitated communication (FC). I have been writing about this for many years. Like many pseudosciences, they rarely completely disappear, but tend to wax and wane with each new generation, often morphing into different forms while keeping the nonsense at their core. FC has had a resurgence recently due to a popular podcast, The Telepathy Tapes (which I wrote about over at SBM). Janyce had this to say:

I’ll be continuing to post critiques about the Telepathy Tapes–especially since some of their followers are now claiming that my student was telepathic. Their “logic” (and I use that term loosely) is that during the picture message passing test, she read my mind, knew what picture I saw, and typed that instead of typing out the word to the picture she saw.

I shouldn’t be surprised by their rationalizations. The mental gymnastics these people go through!

They’re also claiming that people don’t have to look at the letter board because of synesthesia. According to them, the letters light up and the clients can see the “aura” of each color. Ridiculous. I haven’t been able to find any research that backs up this claim. Nor have I found an expert in synesthesia who is willing to answer my questions about this condition, but I’m assuming that, if synesthesia is a real condition, it doesn’t work the way the Telepathy Tapes folks are claiming it does.

For quick background, FC was created in the 1980s as a method for communicating to people, mostly children, who have severe cognitive impairment and are either non-verbal or minimally verbal. The hypothesis FC is based on is that at least some of these children may have more cognitive ability than is apparent but rather have impaired communication as an isolated deficit. This general idea is legitimate, and in neurology we caution all the time about not assuming the inability to demonstrate an ability is due purely to a cognitive deficit, rather than a physical deficit. To take a simple example, don’t assume someone is not responding to your voice because they have impaired consciousness when they could be deaf. We use various methods to try to control for this as much as possible.

Continue Reading »

Apr

29

2025

In my previous post I wrote about how we think about and talk about autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and how RFK Jr misunderstands and exploits this complexity to weave his anti-vaccine crank narrative. There is also another challenge in the conversation about autism, which exists for many diagnoses – how do we talk about it in a way that is scientifically accurate, useful, and yet not needlessly stigmatizing or negative? A recent NYT op-ed by a parent of a child with profound autism had this to say:

“Many advocacy groups focus so much on acceptance, inclusion and celebrating neurodiversity that it can feel as if they are avoiding uncomfortable truths about children like mine. Parents are encouraged not to use words like “severe,” “profound” or even “Level 3” to describe our child’s autism; we’re told those terms are stigmatizing and we should instead speak of “high support needs.” A Harvard-affiliated research center halted a panel on autism awareness in 2022 after students claimed that the panel’s language about treating autism was “toxic.” A student petition circulated on Change.org said that autism ‘is not an illness or disease and, most importantly, it is not inherently negative.'”

I’m afraid there is no clean answer here, there are just tradeoffs. Let’s look at this question (essentially, how do we label ASD) from two basic perspectives – scientific and cultural. You may think that a purely scientific approach would be easier and result in a clear answer, but that is not the case. While science strives to be objective, the universe is really complex, and our attempts at making it understandable and manageable through categorization involve subjective choices and tradeoffs. As a physician I have had to become comfortable with this reality. Diagnoses are often squirrelly things.

When the profession creates or modifies a diagnosis, this is really a type of categorization. There are different criteria that we could potentially use to define a diagnostic label or category. We could use clinical criteria – what are the signs, symptoms, demographics, and natural history of the diagnosis in question? This is often where diagnoses begin their lives, as a pure description of what is being seen in the clinic. Clinical entities almost always present as a range of characteristics, because people are different and even specific diseases will manifest differently. The question then becomes – are we looking at one disease, multiple diseases, variations on a theme, or completely different processes that just overlap in the signs and symptoms they cause. This leads to the infamous “lumper vs splitter” debate – do we tend to lump similar entities together in big categories or split everything up into very specific entities, based on even tiny differences?

Continue Reading »

Apr

28

2025

RFK Jr.’s recent speech about autism has sparked a lot of deserved anger. But like many things in life, it’s even more complicated than you think it is, and this is a good opportunity to explore some of the issues surrounding this diagnosis.

While the definition has shifted over the years (like most medical diagnoses) autism is currently considered a fairly broad spectrum sharing some underlying neurological features. At the most “severe” end of the spectrum (and to show you how fraught this issue is, even the use of the term “severe” is controversial) people with autism (or autism spectrum disorder, ASD) can be non-verbal or minimally verbal, have an IQ <50, and require full support to meet their basic daily needs. At the other end of the spectrum are extremely high-functioning individuals who are simply considered to be not “neurotypical” because they have a different set of strengths and challenges than more neurotypical people. One of the primary challenges is to talk about the full spectrum of ASD under one label. The one thing it is safe to say is that RFK Jr. completely failed this challenge.

What our Health and Human Services Secretary said was that normal children:

“regressed … into autism when they were 2 years old. And these are kids who will never pay taxes, they’ll never hold a job, they’ll never play baseball, they’ll never write a poem, they’ll never go out on a date. Many of them will never use a toilet unassisted.”

This is classic RFK Jr. – he uses scientific data like the proverbial drunk uses a lamppost, for support rather than illumination. Others have correctly pointed out that he begins with his narrative and works backward (like a lawyer, because that is what he is). That narrative is solidly in the sweet-spot of the anti-vaccine narrative on autism, which David Gorski spells out in great detail here. RFK said:

“So I would urge everyone to consider the likelihood that autism, whether you call it an epidemic, a tsunami, or a surge of autism, is a real thing that we don’t understand, and it must be triggered or caused by environmental or risk factors. “

In RFK’s world, autism is a horrible disease that destroys children and families and is surging in such a way that there must be an “environmental” cause (wink, wink – we know he means vaccines). But of course RFK gets the facts predictable wrong, or at least exaggerated and distorted precisely to suit his narrative. It’s a great example of how to support a desired narrative by cherry picking and then misrepresenting facts. To use another metaphor, it’s like making one of those mosaic pictures out of other pictures. He may be choosing published facts but he arranges them into a false and illusory picture. RFK cited a recent study that showed that about 25% of children with autism were in the “profound” category. (That is another term recently suggested to refer to autistic children who are minimally verbal or have an IQ < 50. This is similar to “level 3” autism or “severe” autism, but with slightly different operational cutoffs.)

Continue Reading »

I am currently in Dubai at the Future Forum conference, and later today I am on a panel about the future of the mind with two other neuroscientists. I expect the conversation to be dynamic, but here is the core of what I want to say.

I am currently in Dubai at the Future Forum conference, and later today I am on a panel about the future of the mind with two other neuroscientists. I expect the conversation to be dynamic, but here is the core of what I want to say.

The technique is called

The technique is called  We are all familiar with the notion of “being on autopilot” – the tendency to initiate and even execute behaviors out of pure habit rather than conscious decision-making. When I shower in the morning I go through roughly the identical sequence of behaviors, while my mind is mostly elsewhere. If I am driving to a familiar location the word “autopilot” seems especially apt, as I can execute the drive with little thought. Of course, sometimes this leads me to taking my most common route by habit even when I intend to go somewhere else. You can, of course, override the habit through conscious effort.

We are all familiar with the notion of “being on autopilot” – the tendency to initiate and even execute behaviors out of pure habit rather than conscious decision-making. When I shower in the morning I go through roughly the identical sequence of behaviors, while my mind is mostly elsewhere. If I am driving to a familiar location the word “autopilot” seems especially apt, as I can execute the drive with little thought. Of course, sometimes this leads me to taking my most common route by habit even when I intend to go somewhere else. You can, of course, override the habit through conscious effort. Researchers

Researchers  This is an interesting story, and I am trying to moderate my optimism. Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the major cause of dementia in humans, is a very complex disease. We have been studying it for decades, revealing numerous clues as to what kicks it off, what causes it to progress, and how to potentially treat it. This has lead to a lot of knowledge about the disease, but only recently resulted an effective disease-modifying treatments – the anti-amyloid treatments.

This is an interesting story, and I am trying to moderate my optimism. Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the major cause of dementia in humans, is a very complex disease. We have been studying it for decades, revealing numerous clues as to what kicks it off, what causes it to progress, and how to potentially treat it. This has lead to a lot of knowledge about the disease, but only recently resulted an effective disease-modifying treatments – the anti-amyloid treatments. In the movie

In the movie  I was away on vacation the last week, hence no posts, but am now back to my usual schedule. In fact, I hope to be a little more consistent starting this summer because (if you follow me on the SGU you already know this) I am retiring from my day job at Yale at the end of the month. This will allow me to work full time as a science communicator and skeptic. I have some new projects in the works, and will announce anything here for those who are interested.

I was away on vacation the last week, hence no posts, but am now back to my usual schedule. In fact, I hope to be a little more consistent starting this summer because (if you follow me on the SGU you already know this) I am retiring from my day job at Yale at the end of the month. This will allow me to work full time as a science communicator and skeptic. I have some new projects in the works, and will announce anything here for those who are interested.